'C'mon Get Happy' and 'The Warner Brothers' provide fresh looks at old Hollywood

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A pair of new books by Milwaukee film historians shine fresh light on Hollywood's Golden Age.

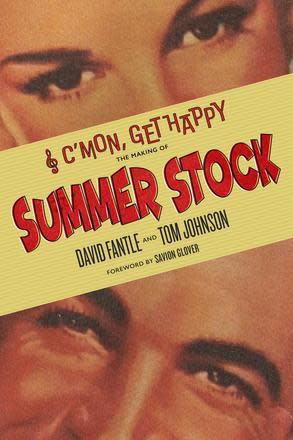

But the books — "C'mon, Get Happy: The Making of 'Summer Stock'" (University Press of Mississippi) by David Fantle, a veteran movie writer and adjunct film faculty at Marquette University, and Tom Johnson; and "The Warner Brothers" (University Press of Kentucky) by Chris Yogerst, a prolific film historian and associate professor of communication at the University of WIsconsin-Milwaukee — share one thing. They bring alive an era in entertainment when larger-than-life personalities made things happen — or had things made happen for them.

Judy Garland, Gene Kelly and the making of 'Summer Stock'

The 1950 MGM musical "Summer Stock" isn't in anyone's pantheon.

Starring Gene Kelly and Judy Garland, it was a throwback to the "let's put on a show" musicals that helped make Garland a star. It's not in the same league as other MGM musicals from the studio's storied heyday," like "An American in Paris," "Singin' in the Rain" and "The Band Wagon," Fantle and Johnson concede. But it has a few things that have kept it on the radar for fans of Hollywood musicals — most of them revolving around Garland.

"Summer Stock" was Garland's final movie with MGM, the studio that had made her a star — and for which she had made a lot of money. But the two years leading up to the making of the movie had been fraught with offscreen drama for Garland, whose battles with pill addiction and flagging self-esteem left her shuttling in and out of rehab facilities. She had already lost starring roles in "The Barkleys of Broadway" and "Annie Get Your Gun," and it was no sure thing that she'd make it through "Summer Stock" either.

Make it through she did. In loving detail, Fantle and Johnson recount the travails of getting Garland through the production, made possible because everyone — from director Charles Walters to co-star Gene Kelly to the songwriters to the crew — was looking out for and taking care of Garland.

And she gave her all, especially in the number from "Summer Stock" that became one of her signatures: the gospel-flavored belter "Get Happy."

But Fantle and Johnson don't let the movie's best-known moments dominate the narrative in "C'mon Get Happy."

They dive deep into every aspect of the movie's production, from conflicts between cast members to songs that didn't make the final cut. Both writers are passionate about classic Hollywood, and over the past 40-plus years they have interviewed many of the stars and creatives they clearly admire. Those in-person interviews give an added dimension to their painstaking research.

And they don't make readers take their word for the reasons to re-examine "Summer Stock"; in one of the book's best moves, they talk with contemporary dancers and choreographers and musicians to put the artistry on screen into broader context.

Like those artists, Fantle and Johnson aren't afraid to show their affection for the movie. Even if you don't agree with their perspective, it's hard to dismiss their enthusiasm, or their effort to create the definitive portrait that "Summer Stock" deserves.

'Warner Brothers': Hollywood's dysfunctional family

Warner Bros., Hollywood's grittier counterpart to MGM, was founded in 1923, so there's been a ton of tributes and histories looking back its storied past, from launching the movies into the sound era to classics like "Casablanca" and "The Adventures of Robin Hood" to the post-Golden Age era with movies like "Bonnie and Clyde" and the "Dark Knight" trilogy.

But one thing that's often missing: the brothers Warner themselves.

Chris Yogerst, who has written books on the beginnings of Warner Bros. ("From the Headlines to Hollywood: The Birth and Boom of Warner Bros.") and the fight against Nazi influence in the movie community ("Hollywood Hates Hitler!"), set out to fill in that gap with "The Warner Brothers."

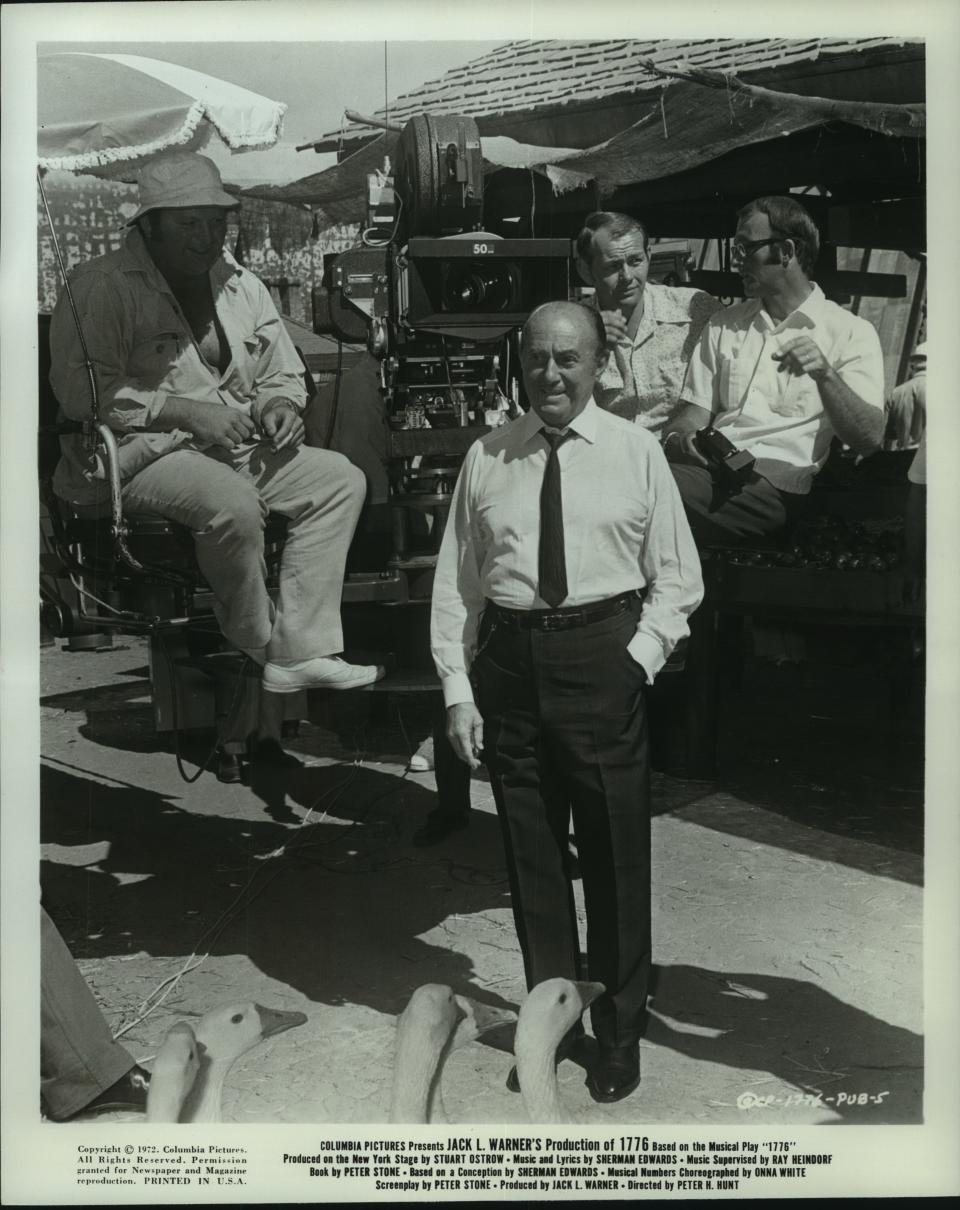

And he succeeds. While Jack Warner, the high-profile, big-ego sibling who oversaw production at the studio for more than 30 years, gets a lot of attention — in most Warner Bros. histories, he's the only one who gets the attention — Yogerst makes clear that, at least in the early decades of the studio, he wasn't the only brother.

Albert, the Quiet Warner, was focused on the business side of things, but also was active in philanthropy. Sam, the Techy Warner, was the one who pushed hardest for the studio to invest in sound, only to die just before the world premiere of the groundbreaking "The Jazz Singer."

If Jack was the face (and cocky attitude) of Warner Bros., Harry, the fourth Warner, was its spirit, or at least its conscience. The movie studio's reputation for making hard-hitting movies about contemporary issues, from injustice ("I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang," "They Won't Forget") to intolerance ("Black Legion," "The Life of Emile Zola") was well-earned, and stemmed from Harry Warner putting the studio's money where its heart was. It didn't hurt that most of the movies made a bunch of money, of course.

Yogerst does a fine job detailing how the brothers' perspectives shaped the movie studio that bore their name, from hardscrabble beginnings to hobnobbing with presidents (a decision that got the studio in trouble when the Red Scare hit Hollywood).

Their stories build up to an act of brotherly betrayal by Jack Warner that I hope someone considers optioning for a movie of its own.

If you're looking for a history of the movies that made Warner Bros. famous, "The Warner Brothers" isn't where you'll find it — although Yogerst does work in most of the studio's greatest and otherwise worthy hits. But as a portrait of the men behind one of the most important brands to shape American culture over the past century, it's a worthy addition to the centennial celebration.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: 'C'mon Get Happy,' 'Warner Brothers': Some new looks at old Hollywood