The Class of '89: How Garth Brooks, Alan Jackson, Clint Black, Travis Tritt changed country music

At 16, Blake Shelton chose a black Takamine cutaway for his first guitar after seeing fellow Oklahoman Garth Brooks play one on TV. Seven-year-old Chris Young bellowed Alan Jackson’s “Don’t Rock the Jukebox” from the aisles of BI-LO in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, so his mother could find him between the cereal boxes and comic books. Dierks Bentley is convinced that Clint Black’s first five songs topped country radio airplay charts because of the frequency he called local country stations around his hometown of Phoenix to request them.

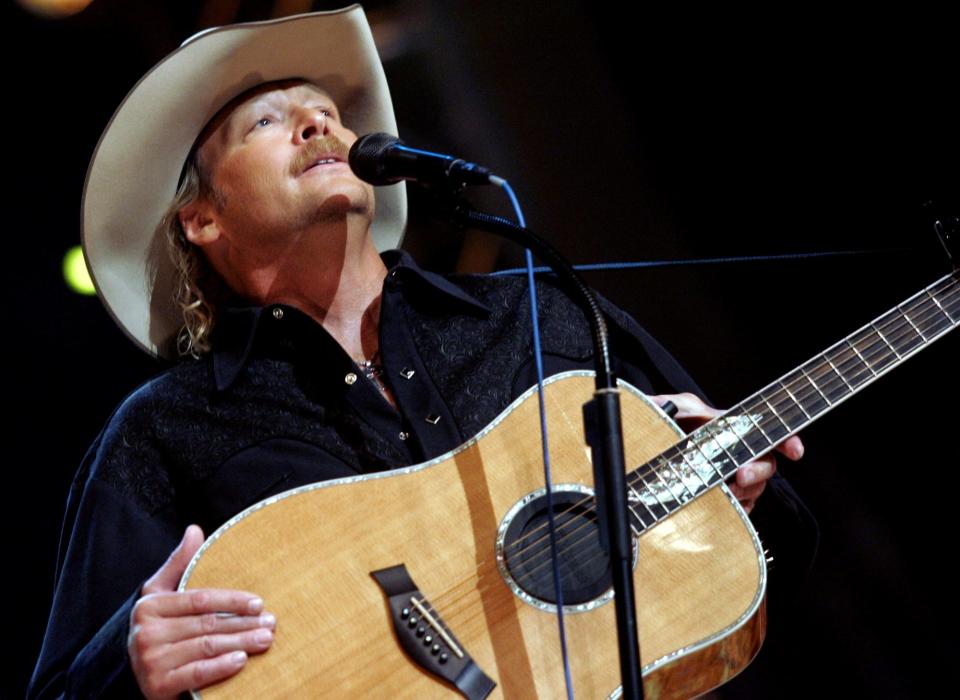

Thirty years ago, country music’s storied “Class of 1989” — led by the meteoric rise of Brooks, Jackson, Black and Travis Tritt — changed the face of one of America’s truest art forms, propelling country music to unprecedented commercial success and worldwide popularity. Jackson’s traditionalism, Tritt’s Southern rock swagger, Black’s refined twang and Brooks’ everyman storytelling combined for a string of hits that would dominate charts for years to follow. Their distinctive voices and nuanced music — at once undeniably modern and deeply rooted in the genre’s past — showed the world there was more to country music than overalls and tobacco spit.

These men challenged the very standards by which country music was viewed, both within and beyond rural America. A generation later, they are the standard. Their legacy is still being written by a new crop of stars whose own music is directly influenced by the foursome.

“When you talk about them, and you look at all the songs that came out of those artists, you don’t get a much more indelible mark than any one of them, much less all ... of them,” said Young, a multiplatinum-selling country singer whose latest hit, “Raised on Country,” is about growing up listening to ’80s and ’90s country music. “Each one had their own lane, and they’re all Hall of Famers to me. I don’t know if there’s another year that’s like that in the history of country music.”

Together, the men are responsible for 64 No. 1 country hits. Jackson delivered 26 chart-toppers, including “Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning).” Brooks, who went into semi-retirement from 2001 to 2014, has 20 No. 1 songs to his name, with pop culture crossovers “Friends in Low Places” and “The Dance” among them. The RIAA declared Brooks the best-selling solo albums artist of the century. Black earned 13 No. 1 hits, spanning from 1989’s “Killin’ Time” to 1999’s “When I Said I Do.” Tritt contributed five hits, including singalong ballads “Help Me Hold On” and “Anymore.”

“It was really special because you could see there was a renewed attraction to country music — our kind of music — that had not really existed before that,” Tritt said of 1989.

For country music, the excitement surrounding the Class of 1989 was not like anything that came before.

“I hate to compare it to The Beatles, but that’s what it felt like, and sometimes that’s frightening,” Black recalled. “When you get people in a crowd, sometimes someone wants a piece of your ear.”

Country music was at a crossroads

The Class of '89 came along at a pivotal moment for country music — an era music critic and author Holly Gleason described as the “credibility scare of the late ’80s.” As is frequently the case in country music, different factions of the genre had opposing views on where it should stylistically be headed.

The outlaw movement of the 1970s and early 1980s, personified by the likes of Johnny Cash, Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings, had given way to the sweeping arrangements and softer pop country of Sylvia, Gary Morris and Restless Heart.

Left-of-center artists Steve Earle, Dwight Yoakam, k.d. lang and Lyle Lovett, among others, rebuked the heavy production with their own brand of alt-country that delved into strains of ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s sub-genres.

Garth: 'Randy Travis saved country music'

At the same time, another splinter group of artists was mounting a revival of traditional country music: plainspoken Texas cowboy George Strait, rodeo maven and two-step queen Reba McEntire, progressive hardcore honky-tonker John Anderson and fleet-fingered bluegrass crossover Ricky Skaggs. When a dancehall dishwasher named Randy Travis brought his North Carolina baritone to songs including “1982” and “On the Other Hand” in 1986, his ringing ache ignited the genre and paved the way for the Class of 1989.

“Randy Travis saved country music, in my opinion,” Brooks said. “I don’t know of any artist who took a format and turned it 180 (degrees) back to where it came from and made it bigger than it was then. And thank God for guys like Skaggs and Strait who were there to hold the fort down with him.”

It was these artists — Travis, Strait and company — who most directly paved the way for the success of the Class of '89, three so-called "hat acts" and Tritt (who refused to cover his mullet with a Stetson).

Along with a return to traditional instruments and forms, the Class of '89 brought a new kind of sexuality to country music. Previously, adjectives no saucier than “handsome” were used to describe male country artists. But fans saw Black as a twinkle-eyed cowboy dream. Brooks was the scrappy, down-to-earth football star. And Jackson’s understated, classic approach elicited comparisons to a modern-day Hank Williams.

“Desirability brought the (median) age of (fans) down and introduced the idea of young, hormonal bliss,” said Gleason, who wrote the award-winning book “Woman Walk the Line: How the Women in Country Music Changed Our Lives."

“Who doesn’t love a cowboy?” she questioned. “And if Clint Black was the cowboy idol, Garth Brooks was the everyday hero. You knew he would take his hat off when your mom walked out on the porch.”

Busting boundaries

Music industry veteran Joe Galante signed Black to his record deal with RCA Records 30 years ago. More important than the singers, their looks or even how many concert tickets they sold, he believes, is the quality of the songs they recorded. No one back then had crossover hits, Galante said.

Yet people outside country music fans heard these songs. And, they wanted more.

“These were iconic country songs, but they were much bigger than the format,” he explained. “I think that’s the power of the singer, the power of the song and the power of the records they made. The first singles on these records were followed by bigger and bigger and bigger songs and they were on those albums. There was a catalyst that kept these records selling for years — not for a year — just because they had that kind of depth.”

The depth also came with a true individuality, Gleason notes.

“Across that line of artists, they all have enough in common that you can put them on the same shelf, but they’re all individual enough to know which stuffed animal is which,” she explained.

The men launched their professional careers in 1989, but it took a couple of years to pick up momentum. As the singers climbed, Nielsen in 1991 implemented SoundScan, a tool that for the first time accurately counted album sales. (Before SoundScan, sales data was tabulated by weekly calls to record shops.)

The indisputable numbers proved country music resonated well outside of rural America.

Revelations about this music’s vast appeal led to television performances that grew country music’s popularity at an even greater pace. The heightened national exposure led to new consensus that country music resonated with fans coast to coast.

“That was really the first time — especially with Garth — that people stood up and said, ‘Holy s--t, you guys in Nashville really are selling records. You’re doing real numbers,' ” Galante recalled.

The Class of '89 was part of a larger movement

While Brooks, Black, Jackson and Tritt are the Class of '89’s superlatives, they weren’t the only singers to break through the genre that year. Vince Gill and Mary Chapin Carpenter were already familiar faces on Music Row, each having released albums to limited commercial fanfare. But it was in 1989 that Gill cemented his place in the genre with “When I Call Your Name,” a lonesome piano ballad with the hook “nobody answers when I call your name.” Carpenter, an Ivy League educated folk-country singer from New Jersey, was also coming into her own in 1989 with “Never Had It So Good” and “Quittin’ Time.”

However, it's a 1990 performance on the CMA Awards that viewers still remember. Carpenter was dressed in a loose periwinkle pantsuit — sans appliques and rhinestones — and sang about the perils of being an opening act.

“In 2½ minutes with that cute Chapin smile, it was like, 'Boom! Mary Chapin Carpenter is a factor,’ ” Gleason remembers.

Country singer Carly Pearce added: “I grew up loving Mary Chapin Carpenter and just how out of the box she was. She was a little left of center. She wasn’t about glitz and glamour. She just had her own little edgy thing, which I think is powerful and is something I don’t feel we have right now.”

Keith Whitley didn’t have his breakthrough moment in 1989 — that came in 1985 with “Miami, My Amy.” But when today’s country singers, including Young and Michael Ray, talk about the year, Whitley inevitably comes up. In 1988 his success heightened with his album “Don’t Close Your Eyes.” Whitley’s unexpected and untimely death in 1989 combined with the collection’s popular self-titled track and other hits “When You Say Nothing at All” and “I’m No Stranger to the Rain” — the Country Music Association’s single of the year — made the Kentucky baritone an enduring force in the genre.

“In my opinion, you don’t get a better country voice than Keith Whitley,” Ray said. “We’ll look back on 1989 as the year that changed it all. They’re the class that opened so many doors for us as artists now. Thirty years later, we’re still reaping the benefits.”

'Dude quake' sent shock waves well into the '90s

As Travis was the precursor to the Class of 1989, Black, Brooks and Jackson led to what Gleason calls the “dude quake” that started in the '90s — artists such as Shelton, Kenny Chesney, Billy Ray Cyrus, Joe Diffie, Brooks & Dunn and, to some extent, Tim McGraw.

“The dude quake was about dudes who went to the church of boys will be boys, but they never forgot what girls liked and girls were never an appendage,” Gleason said. “To quote Kenny (Chesney), ‘Our hearts still skipped a beat when those girls shimmied off their old cutoffs.’ Those boys were highly attuned to the fact that it’s fun to go mudding in your truck, but nothing is as fun as skinny-dipping with some girl. And, it was a world of equally balanced dualities.”

Those themes further engaged young audiences that still buoy the format. Country music historian and author Robert Oermann believes today’s country music following is one of the Class of ’89's most important legacies.

“That was a huge moment,” he said. “We had youth acts before and we had youth acts after, but that was the first explosion. In order to sell the numbers they did, they had to attract people who buy albums, and that’s youth. We’ve had that youth audience since then.”

What country music hasn’t consistently had, Oermann added, was the authenticity delivered by Brooks, Black, Tritt and especially Jackson.

“Music Row forgets over and over again their core mission,” he explained. “(Country music executives) are like, ‘Oh, people really like that. They really like country music.’ It’s like you’re watching a circus parade and they (forgot the elephants). Then they go back to making pop s--t."

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: How Garth Brooks, Alan Jackson, Clint Black changed country music