Who Was Clara Bow? The Real Story of Taylor Swift’s Tortured Poets Department Heroine

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Composite. Getty Images

What would it be like if you achieved your wildest dream, and it turned into your worst nightmare? That was what happened to Clara Bow (1905–1965), a groundbreaking actor who electrified the silver screen a century ago — and who now lends her name to a song on Taylor Swift’s new album The Tortured Poets Department.

During the silent film era, Bow gained renown as Hollywood’s first sex symbol and the original “It Girl.” From 1923 to 1933, her vivacious screen presence enchanted the nation’s filmgoers. Then, when she was just twenty-eight years old, Bow walked away from her career. Her films remained largely forgotten until the late 1960s, when cinematic preservationists and archivists began directing overdue attention to her extraordinary talent. Examples of her work now available on YouTube reveal a performer whose refreshing spontaneity and emotional authenticity were well ahead of their time.

The Tortured Poets Department includes a song titled “Clara Bow” that seems likely to rekindle interest in the silent film star. Although Bow’s heyday preceded Swift’s by nearly 100 years, there are obvious parallels between her story and the pitfalls of fame that female celebrities continue to navigate today.

Clara Bow

Bow’s dreams of stardom were fueled by the traumatic circumstances of her youth. Raised in a string of squalid tenements in Brooklyn, New York, she bounced between a mother suffering from severe mental illness and a frequently absent father who struggled with alcoholism. At school, Bow’s ragged clothing, auburn hair, and tendency to stutter made her stand out, and she was often bullied by the other girls.

The street-smart boys in her neighborhood were more welcoming. They respected her prowess as the fastest runner, best pitcher, and toughest fighter in their group. Reflecting on her years as a “tomboy,” Bow later recalled in a 1928 interview with Photoplay magazine, “I was as good at any game as any of the boys. And just as strong. They always accepted me as though I had been one of themselves…. I never felt there was any difference between us.”

Clara Bow Classics

Whenever she could scrounge up a few pennies, Bow took refuge from the unpleasant realities she faced at home and school by escaping into the wonderland of the movie theater. “For the first time in my life I knew there was beauty in the world,” she told Photoplay. “For the first time I saw distant lands, serene, lovely homes, romance, nobility, glamour. My whole heart was afire, and my love was the motion picture. Not just the people of the screen, but everything that magic silversheet could represent to a lonely, starved, unhappy child.” Mesmerized by the fantasies projected on the screen, Bow grew determined to become an actor herself.

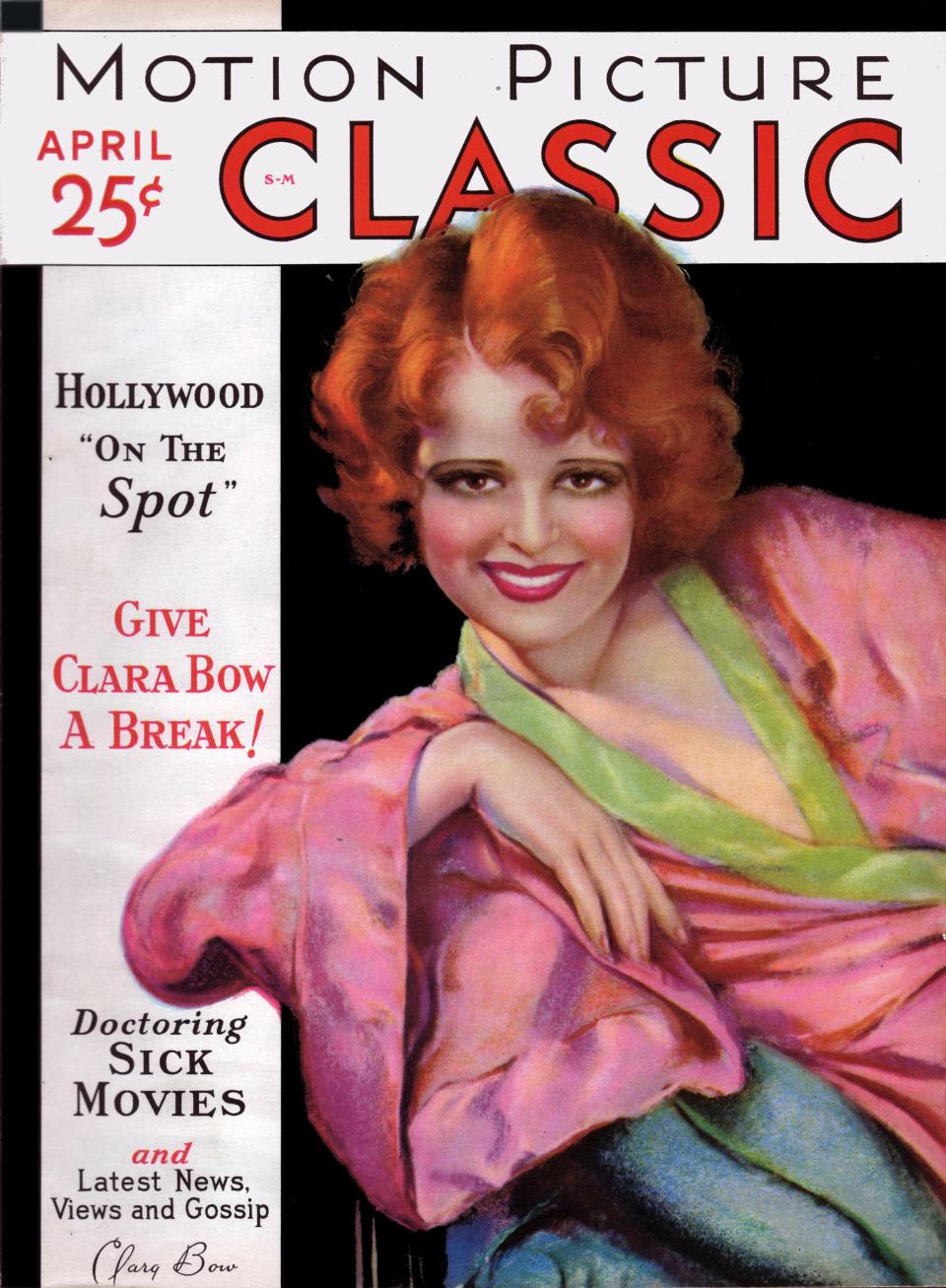

In 1921, a nationwide “Fame and Fortune” contest caught Bow’s attention with its offer of a motion picture role as first prize. She sent in her photograph and, to her amazement, was invited to take a screen test. Another screen test followed. And then another. Finally, after five screen tests, Bow was declared the contest’s winner. The January 1922 issue of Motion Picture Classic magazine ran her photograph under the title “A Dream Comes True.” Indeed, at the young age of 16, Clara Bow seemed on the way to making her cherished fantasy a reality. Notably, Taylor Swift was also sixteen when she released her debut album.

Bow’s promised movie role came to nothing when the scenes she filmed for Beyond the Rainbow (1922) ended up on the cutting room floor. Unwilling to give up, she attempted to use her notoriety as the Fame and Fortune contest winner to land other acting jobs. “I wore myself out trying to find work, going from studio to studio, from agency to agency, applying for every possible part,” she told Photoplay. At last, she landed the role of a feisty stowaway in Down to the Sea in Ships (1923). The small part drew on her rough-and-tumble childhood experiences as “one of the guys” on the streets of Brooklyn. She gave a spirited performance that leapt off the screen and convinced a producer to send her to Hollywood for a three-month trial. In July 1923, still shy of her 18th birthday, Bow boarded a train heading west to California.

In Hollywood, Bow’s performances swiftly drew attention. Her exuberant energy and expressive face lit up the screen. In December 1923, Motion Picture magazine reported on the many film companies that were seeking Bow’s services. In an era when studios rapidly churned out films to keep up with popular demand, she worked relentlessly, sometimes performing with two or three different film companies at the same time.

In many of her roles, Bow personified the iconic 1920s “flapper”: a fun-loving, sexually liberated party girl who drank, smoked, used slang, bobbed her hair, wore makeup, and shortened her skirts. Like the tomboys that were also part of her repertoire, Bow’s flapper roles challenged conventional gender norms. She endowed her performances with an assured self-confidence and frank sensuality that heralded a new model of modern femininity. “I had to make a niche for myself,” Bow explained to Photoplay in 1928. “If I'm the ‘super-flapper’ and ‘jazz-baby’ of pictures, it's because I had to create a character for myself. Otherwise, I'd probably not be in pictures at all.”The risqué themes suggested by titles such as Daughters of Pleasure (1924), My Lady’s Lips (1925), and The Adventurous Sex (1925) culminated in the film It (1927), in which Bow played a shop clerk intent on seducing her boss. Adapted from a novella by Elinor Glyn, the film showcased the potent “It factor” that Bow projected onscreen. What was “It”? An irresistible combination of charismatic charm and alluring sex appeal that Bow possessed in spades.

In the immediate aftermath of It, Bow’s superstardom continued to grow. At the height of her fame in 1929, she received 45,000 fan letters each month. Female fans imitated her bee-stung lips, darkly outlined eyes, and bobbed bright red hair. When sales of henna hair dye tripled, the boom was attributed to Bow wannabes.

Having endured years of destitution and misery, Bow suddenly found herself with the wealth and fame she had always dreamed of. Still in her early twenties, she responded by throwing herself into a string of love affairs and indulging in the many pleasures that had been absent from her hard-scrabble upbringing. As she explained to an interviewer in 1928, “I cannot quite trust life. It did too many awful things to me in my youth. I still feel that I must beat it, grab everything quickly, enjoy the moment to the utmost, because tomorrow, life may bludgeon me down.”

While other actors carefully curated their public images, Bow was unapologetically herself. Her refusal to abide by the unspoken social codes of Hollywood made her an easy target for jealous colleagues and tabloid gossip. True or not, salacious stories sold papers, and Bow became the subject of some of the most outrageous claims. Her unguarded honesty only made the situation worse. Without a media-savvy publicist to guide her, she agreed to an interview in 1928 in which she candidly revealed the squalid details of her early life, including her mother’s attempt to kill her while in a psychotic state. More unflattering information emerged during a 1931 court case in which a former assistant shared correspondence and financial documents that seemed to expose Bow’s hard-partying lifestyle.

Bow had kickstarted her career by tapping into the Roaring Twenties’ mood of hedonistic overindulgence. “I'd created a Clara Bow … who fitted the public desire and the public imagination,” she acknowledged. However, the perception switched when the stock market crash of 1929 ushered in the Great Depression. Suddenly, Bow seemed to personify the wasteful excesses of the previous decade. Besieged by vicious rumors, exhausted from overwork, and unnerved by constant surveillance, Bow stepped away from the limelight in 1930. “All I ask is to be let alone and to have the privacy everyone is entitled to,” she told Motion Picture. But in Hollywood, “Your life isn't your own for a minute. You can't love the man you want to, or get married, or have children, without the whole world prying into your affairs, asking impertinent questions. If you don't tell them every intimate detail of your life, they think you're disagreeable and high-hat.”

Bow’s comments reveal how little has changed for female celebrities since the early 20th century. If anything, technology has magnified the scrutiny under which stars like Taylor Swift conduct their lives. Like Bow, Swift has endured criticism for her romantic life and been smeared by inaccurate tabloid gossip. Yet Bow did not have to deal with social media and the internet, both of which abound with rumors about Swift and timelines tracking her romances. Swift clapped back at invasive media scrutiny with the release of her reputation album in 2017, issuing her own magazines with back covers parodying scandalous tabloid headlines.

Swift shares with Bow a remarkable emotional honesty and openness that endear her to fans but also encourage the rumor mill. Like her predecessor, Swift has experienced the painfully fickle nature of celebrity. “I’ve been raised up and down the flagpole of public opinion so many times,” Swift told TIME in 2023. “I’ve been given a tiara, then had it taken away.” Those words could easily have come from Clara Bow.

Following a two-year hiatus during which she tended to her mental health, Bow made two highly regarded sound pictures, Call Her Savage (1932) and Hoopla (1933). After that, she left Hollywood for good, retiring to a ranch in Searchlight, Nevada, where she lived with her husband, the actor and politician Rex Bell, and their two sons. By then, she had come to realize that stardom was not the dream come true that she had expected it to be. As she told Motion Picture, “You spend all your youth and all your energy to attain the thing you thought you wanted more than anything else in the world, and when you get it, you find you don't want it. It not only doesn't bring you happiness, but you find it has robbed you of all the other things that might have given you happiness.”

Abandoning the dream career that had dominated her childhood fantasies seemed the best path forward for Bow. As she explained to a Los Angeles Herald journalist in 1932, “I want somethin’ real now.” After the massive success of the Eras Tour and in the midst of a new love story, perhaps Taylor Swift is after the same thing.

This article was produced with Made By Us, a coalition of more than 200 history museums working to connect with today's youth.

Originally Appeared on Teen Vogue

Want more great Culture stories from Teen Vogue? Check these out:

A New Generation of Pretty Little Liars Takes on the Horrors of Being a Teenage Girl

Underneath Chappell Roan’s Hannah Montana Wig? A Pop Star for the Ages

Donald Glover’s Swarm Is Another Piece of Fandom Media That Dehumanizes Black Women

On Velma, Mindy Kaling, and Whether Brown Girls Can Ever Like Ourselves on TV

Gaten Matarazzo Talks Spoilers, Dustin Henderson, and Growing Up on Stranger Things

How K-pop Stars Are Leading Mental Health Conversations for AAPI People and Beyond

Meet the Collective of Philly TikTokers Making You Shake Your Hips

The Midnight Club Star Ruth Codd Isn’t Defined By Her Disability