City trailblazer: Music was saving grace for first Black in South Bend Symphony

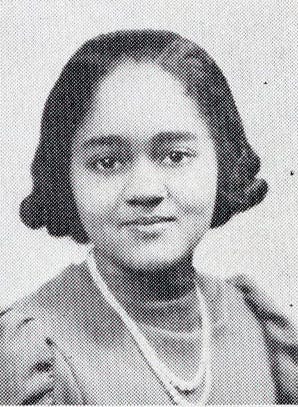

SOUTH BEND — Armed with a Stradivarius violin, city trailblazer Rosemary Sanders grew up quiet and shy, a girl who liked to read and listen to music.

“She was always thinking very deeply,” her daughter, Helen Ursery-Binion, recalls.

Sanders’ innate musical talent led her to become the first Black musician in the South Bend Symphony Orchestra. It meant enduring the racial slights of the 1930s and 1940s, but across the decades yet to come, music would prove more powerful.

Feb. 10, 2023: Viewpoint: Classically trained Rosemary Sanders of South Bend was the invisible player

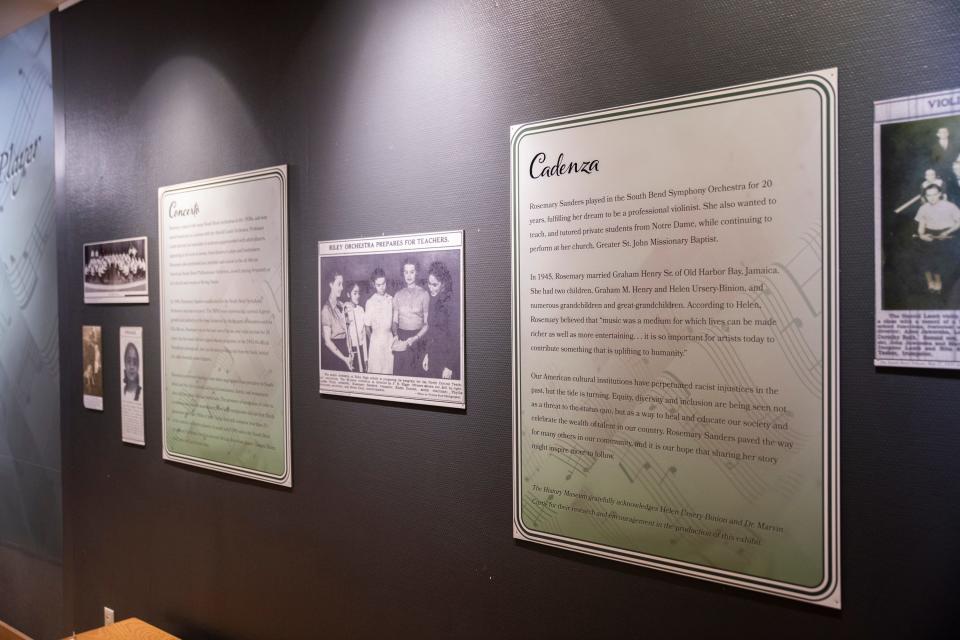

The “Trailblazers: Legacies of Excellence” exhibit at The History Museum, on display through Oct. 1, delves into her life and her mark on the symphony. And Marvin Curtis, who became the SBSO board's president on July 1, is working on a documentary film that, he hopes, will lift her from the “invisible” status of so many other Black classical musicians and composers.

The Tribune joined in Curtis’ recent interview with Ursery-Binion about her mom, as the camera of local filmmaker Chuck Fry rolled.

Born in Chicago in 1921, Sanders’ parents sent her to South Bend for treatment at age 5 because she’d come down with tuberculosis. She lived with her aunt and uncle, Helen and Rolley Sanders, who adopted her.

Hard as it was to leave her parents, that may have been her gateway to music. The Sanders worked for a wealthy family on west Washington Street — Helen as head of household staff, Rolley as chauffeur. They were “the help” for Gertrude Oliver Cunningham, whose father, J.D. Oliver, was an industrialist and owner of the local Oliver Chilled Plow Works.

Ursery-Binion said the Cunninghams paid “the help,” as they called them, in cash so they’d avoid paying taxes and had a caring, “open door policy.” They’d help with medical care and whatever the staff needed.

Cunningham and her husband saw young Rosemary’s musical interest and let her play the piano in their house, even teaching her to play a few songs. The first one she mastered was “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

Young Rosemary also asked to play Mrs. Cunningham’s violin, which she did. That led Mrs. Cunningham to buy her a Stradivarius violin.

Earning her symphony seat

The girl then studied violin under the private guidance of the SBSO’s concertmaster, George Zigmont Gaskas, and took weekly train trips to study violin at Columbia College’s Sherwood Music School in Chicago, for which the Cunninghams paid.

She attended Riley High School from 1935 to 1939 as a straight-A “loner” student who “was all about her music and her studies,” Ursery-Binion says.

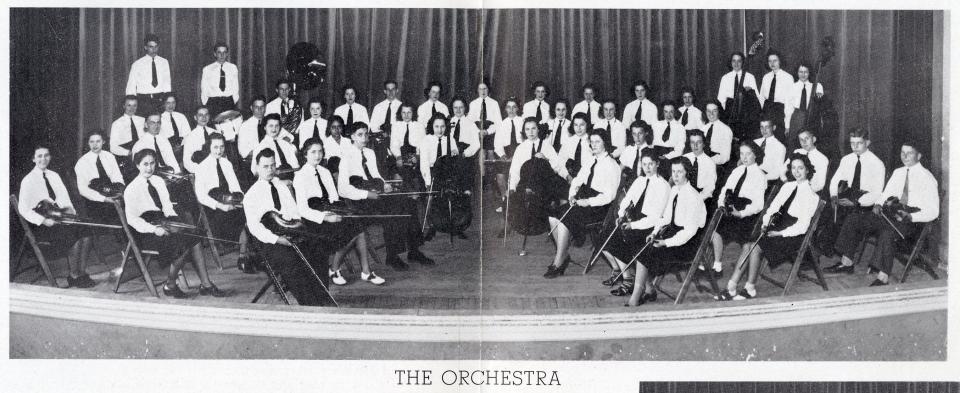

She played in the school’s 65-piece orchestra and served as its treasurer. She was also the only Black student at Riley at the time, from what Ursery-Binion and Curtis can tell.

Ursery-Binion said it seemed her mother felt “a little bit odd,” having felt rejected because her parents had given her away.

“I think that’s why the Cunninghams were so loving to her — they wanted to bridge that gap,” she said.

After high school, Sanders tried to enter the nursing school at South Bend’s Memorial Hospital but was told they didn’t accept students of color.

“But she continued to play her music, and it was her saving grace,” Ursery-Binion said.

Sanders could hear a song and just play it. She did solos and played with other local orchestras, including the all-African American South Bend Philharmonic Orchestra.

'At long last': South Bend Symphony shines a light on music, influence of Black composers

Her talent earned her a role in the SBSO in 1940, where she performed for 20 years. As the only Black in the orchestra, her name didn’t appear in programs. In a formal photo of the SBSO in the mid-1940s, she is seated behind the other musicians with just her head showing. She also couldn’t be in the restroom at the same time as a white person.

It led her to feel isolated, out of place and at times unwanted, but Ursery-Binion said, “There again, her love for music succeeded all of this.”

When the thrill was gone

Sanders went on to teach private piano lessons to University of Notre Dame students, who would come to their home.

“I’d have to go to my bedroom and play with my dolls, and I’d better not make a sound,” Ursery-Binion recalled.

Sanders, who was self taught on the piano, also played at her home church, Greater St. John Missionary Baptist Church.

Ursery-Binion followed her mom’s footsteps to a small degree, learning to play violin from her mother, as well as from the same SBSO concertmaster who’d taught her mom. She went on to play at Riley, too. And although she didn’t go to a prestigious music school, as her mother had, Ursery-Binion did sing and travel with the church choir.

Unlike her mom, she did make it into Memorial Hospital’s nursing school, as times had changed somewhat, and pursued a nursing career.

Nov. 17, 2022: Southold's first Black director taps her ballet childhood for broader reach

Her mother, though, reached a point where she didn’t play anymore. Sanders had composed songs, but that had stopped, too. She was coping with undiagnosed post-partum depression, a condition that led her husband, Graham Henry Sr., to leave because he didn’t understand what it was or how to deal with it.

Because of her condition, Sanders wasn’t able to function and care for her two children, Ursery-Binion and her brother, so they moved in with their grandparents when they were 5 and 7.

The house that they lived in — which their grandparents bought in 1916 on Bowman Street on South Bend’s southeast side — suffered a fire in 1979. Sanders’ Stradivarius was lost. By then, she wasn’t showing any interest in it.

But the house was repaired and remains in the family today. Ursery-Binion, who moved to Las Vegas a year ago, recently turned the house over to her son, who’s renovated it and is renting it out.

Violin restores her joy

In 2016, Sanders was 90 and living at the Sanctuary at St. Paul’s in South Bend. Ursery-Binion would bring some of her mom’s favorite music CDs. The activities staff would play them.

She also bought a violin and took it to her mother, urging her to play.

“She kept saying, ‘I don’t want to.’ I said, 'At least hold it,’” Ursery-Binion recalled. “I put it in her hands, and it was amazing."

Sanders had lost her sight, but her hands remembered how to grasp the instrument. A light went on. It was as if she momentarily sat with the orchestra again.

“For two seconds, that bow went up and down,” Ursery-Binion said. “That was the most joyous time I saw in her in her later years.”

Sanders died in 2017. Ursery-Binion has been writing a journal for eight years about her life with her mother, calling it “Tip of the Iceberg” to reflect both what was seen and the hidden “darkness and unknown” below the surface.

She hopes it will be a book from which, she said, “Others will heal from their untold stories and gather courage and wisdom from it.”

On the music her mom made, she said, “You can’t destroy anything that creates joy, not only in yourself but in other people.”

On exhibit

● What: “Trailblazers: Legacies of Excellence”

● Where: The History Museum, 808 W. Washington St., South Bend

● When: through Oct. 1

● Hours: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Mondays through Saturdays and noon to 5 p.m. Sundays

● Cost: $11-$7; free for members and ages 5 and younger

● For more information: Call 574-235-9664 or visit historymuseumsb.org.

South Bend Tribune reporter Joseph Dits can be reached at 574-235-6158 or jdits@sbtinfo.com.

This article originally appeared on South Bend Tribune: First Black musician in South Bend Symphony a trailblazer with violin