Chuck D on the 35th anniversary of Public Enemy's It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

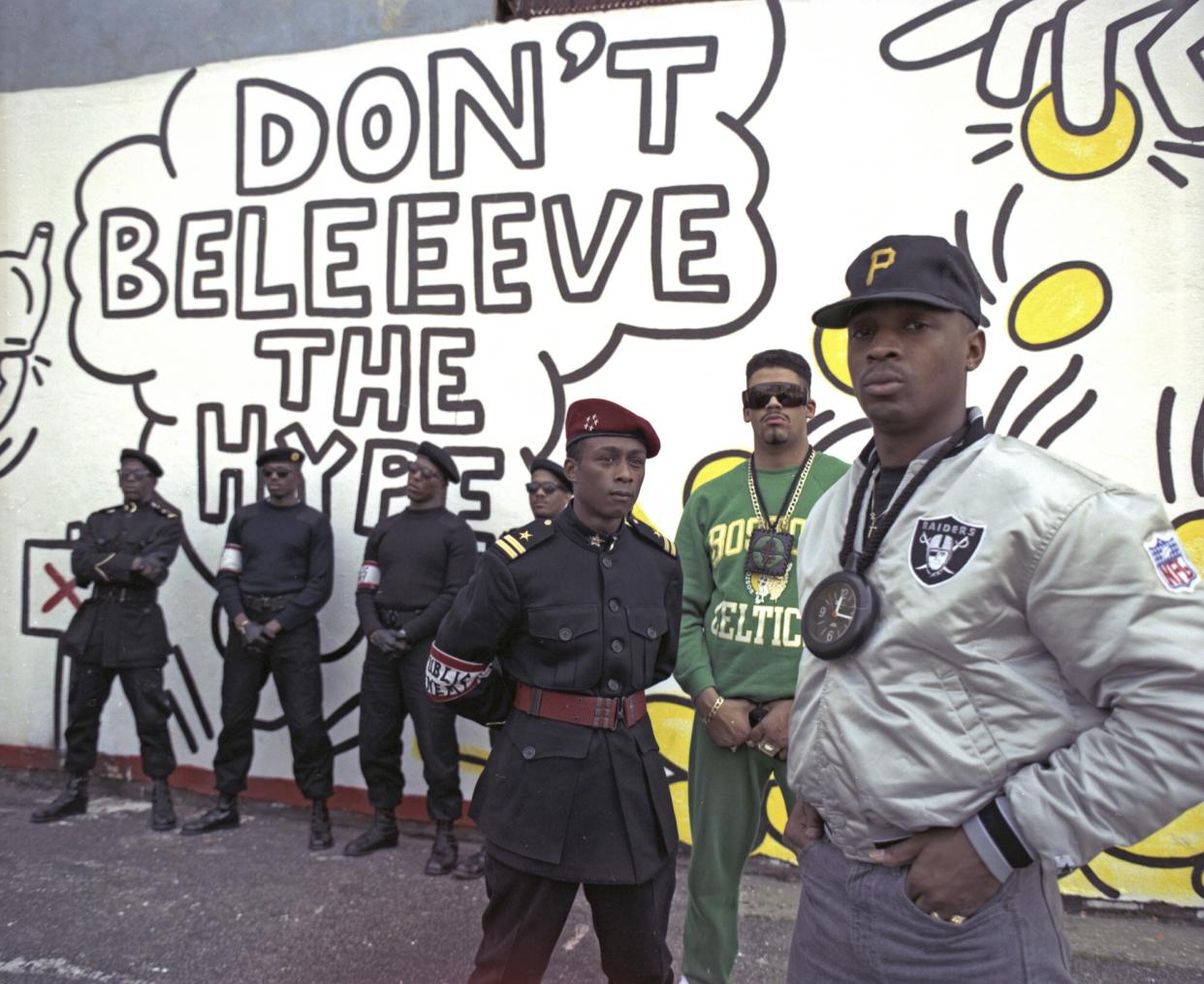

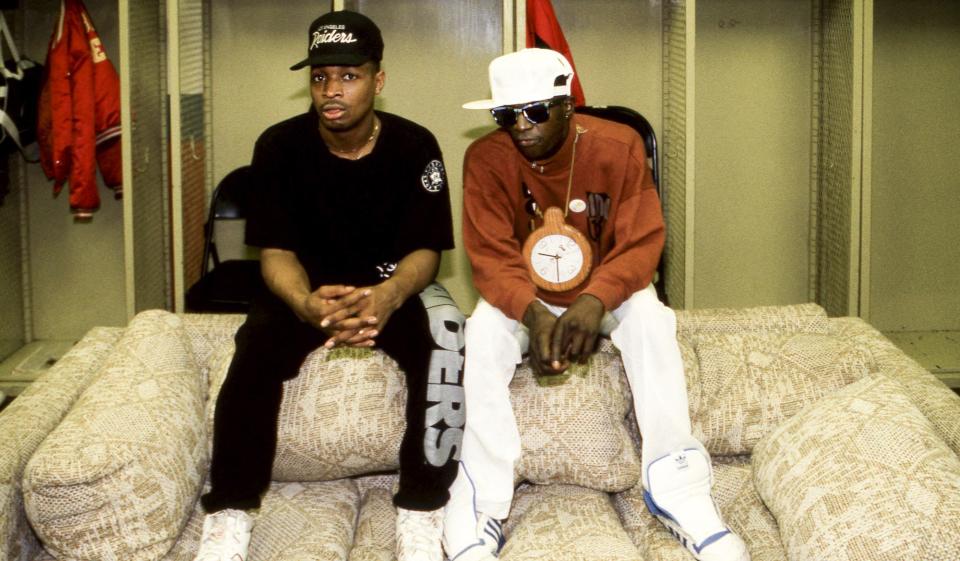

Jack Mitchell/Getty Images Public Enemy

Thirty-five years ago — on June 28, 1988 — the music world exploded, courtesy of a Molotov cocktail thrown by a group of former Long Island radio and club DJs. This collective — fronted by rappers Chuck D and Flavor Flav and DJ Terminator X, as well as a production team who literally called themselves the Bomb Squad — had already made their mark under the name Public Enemy, and a blistering first album on Def Jam titled Yo! Bum Rush the Show.

That debut announced the band as an uncompromising force in the still-emerging hip-hop scene, with song titles like "You're Gonna Get Yours," a repeating text crawl on the cover reading "THE GOVERNMENT'S RESPONSIBLE," and the now famous Public Enemy logo featuring a silhouette of a Black man in a rifle's crosshairs. But even that bold introduction could not have prepared anyone for what would come next.

Public Enemy's second Def Jam album, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, was a combative and creative leap forward not just for the band, but for the entire genre, taking rap to uncharted new places both lyrically and musically. A political manifesto to the Black community, It Takes a Nation… preached self-empowerment and Black power while also admonishing everything from playing-it-safe radio stations to corner dealers for "selling drugs to the brother man instead of the other man."

The album's vitality came not only from Chuck D's rapid-fire delivery and the hype-man antics of Flavor Flav, but also from its ear-bending production style — from a team that included Hank Shocklee, Keith Shocklee, Bill Stephney, Eric "Vietnam" Sadler, Rick Rubin, and Carl Ryder — that sought to mimic the group's energetic live show with faster beats, samples upon samples, and an abundance of vocal sound bites taken from various speeches and recordings spliced throughout the record.

Whether it was the pure speed of "Bring the Noise"; the pulsating, horn-infused jazz swing of "Night of the Living Baseheads"; or the ominous, piano-laden prison-riot thriller-movie vibe of "Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos," It Takes a Nation… was not only a manifesto, it was also an emphatic declaration of what hip-hop could be, opening up avenues of unbridled creativity and raw passion that previously seemed off-limits. And it is that mix of intensity and innovation that makes It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back the greatest rap album of all time.

On its 35th anniversary, EW sat down with Public Enemy frontman Chuck D — who also just released a series of illustrated journals titled STEWdio: The Naphic Grovel ARTrilogy of Chuck D — to deep dive into one of the most important and influential releases in music history.

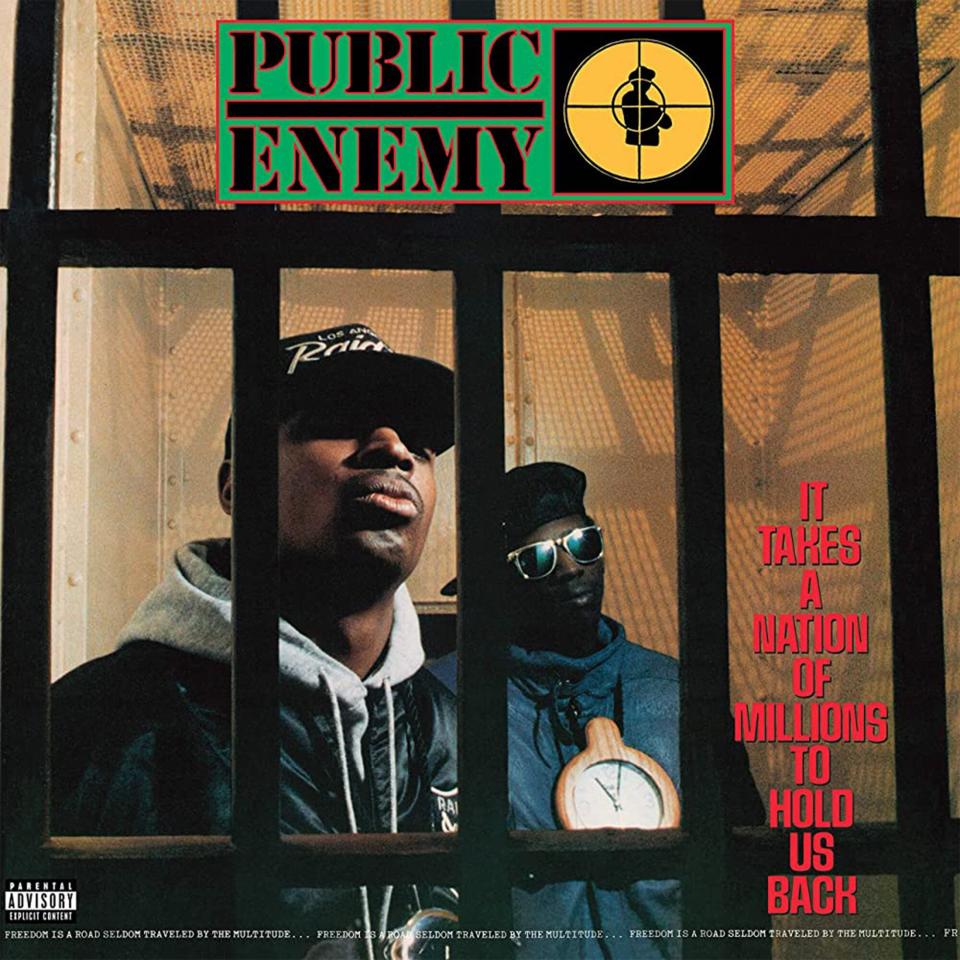

Def Jam 'It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back' by Public Enemy

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: The thing that bowled me over when I first heard this album as a teenager in 1988 was the attitude and intensity. Was that something you all were consciously trying to capture on wax?

CHUCK D: Well, our first album, Yo! Bum Rush the Show, was a culmination of a lot of different things, and on our first tour, we realized that one thing that will set us from the rest of the pack is going up another five or 10 beats per minute and speeding it up. Performance-wise on stage, we could step up to being rather physical and keep up with it, so why not? We came from an athletic background, and we thought a lot of people were music lovers and musicians, and they were kind of slow in the pocket. I said, "Well, maybe our advantage is to never let them see you be slow, weak, or at a tempo where you're just bopping. Let's raise the intensity."

What were some of your biggest influences when you were making this record?

Bob Marley, James Brown. Bill Stephney loved the Clash, and we just poured it all in the blender because we knew that hip-hop was a culmination of records. From the Rolling Stones to the O'Jays, there was sights, sounds, bits and pieces, especially live. That's why with It Takes a Nation of Millions…, we wanted to say hip-hop is not just in the United States. The first words you hear are from London. We also wanted you to know that hip-hop at its best is a live performance. That's why we cut excerpts from our live performance over in London… New Yorkers will always pride themselves on being the next step ahead, but we threw it back at New York and everywhere else like, "Well, you all are actually behind because this is the new movement, and it's got power and speed." I think that's the first two things that It Takes a Nation… signify. A: It happened in London. And B: It was live at a concert that you wasn't at.

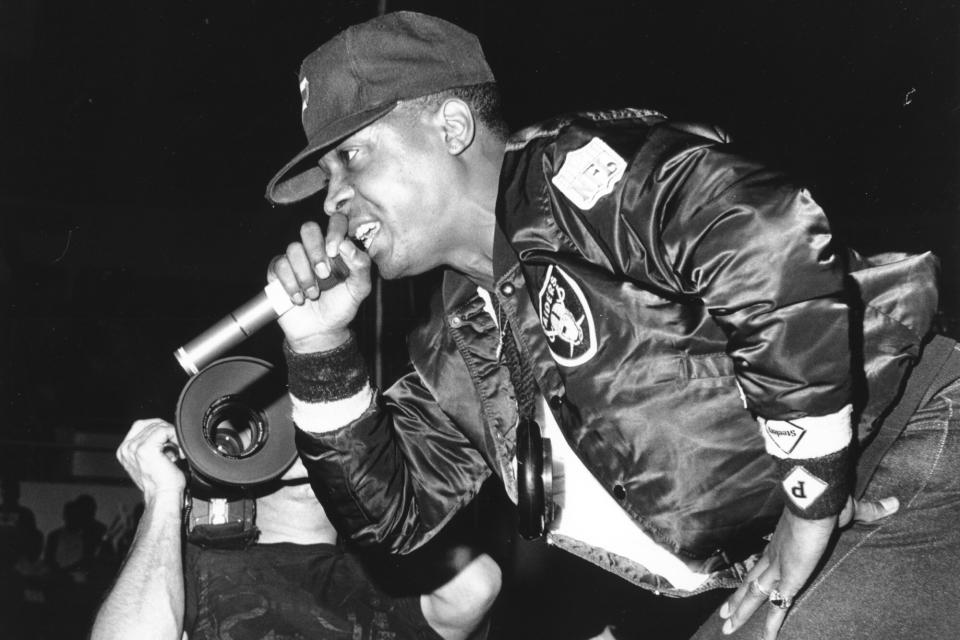

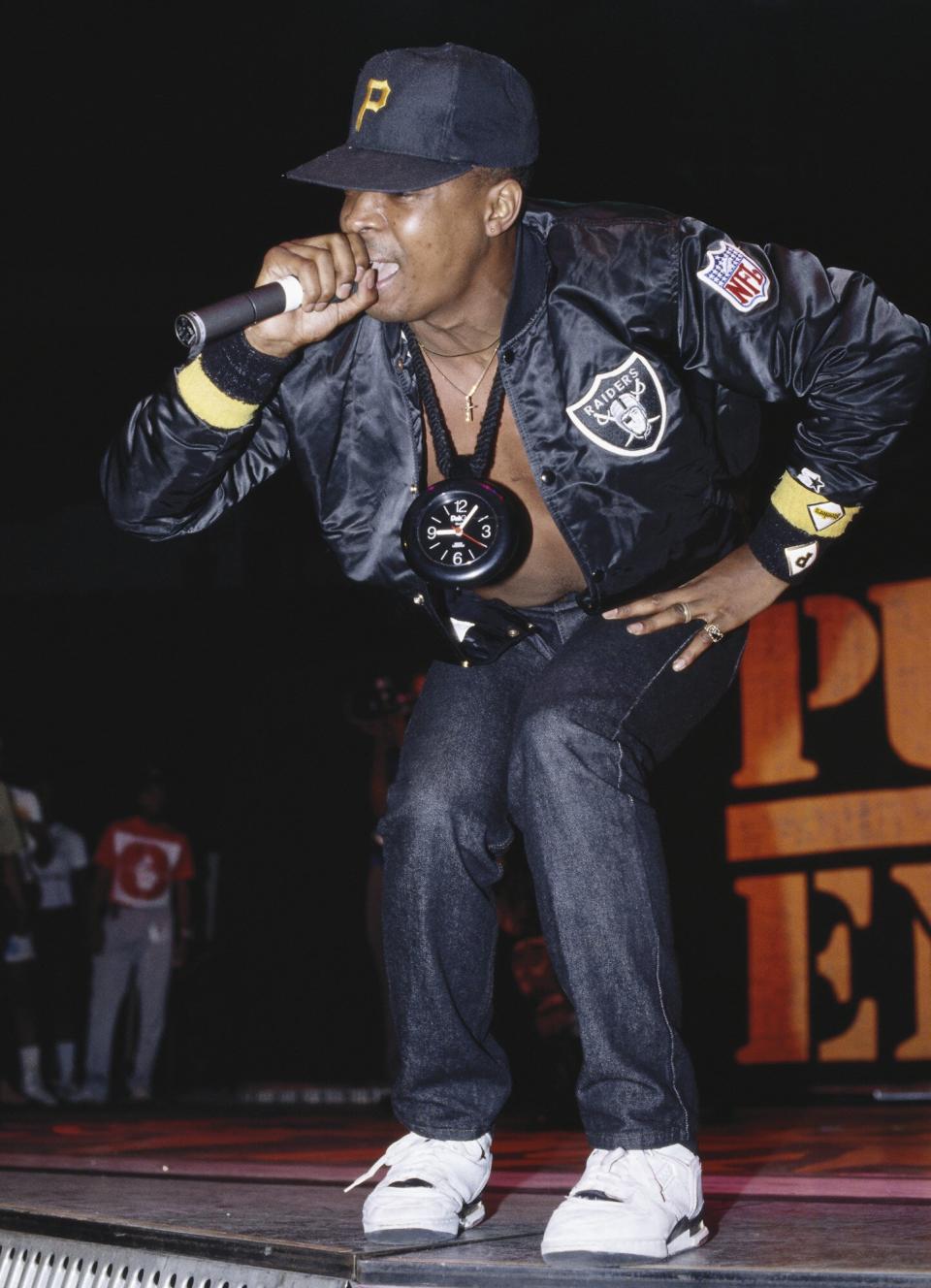

Al Pereira/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images Chuck D of Public Enemy

Speaking of the album opening with the London live stuff, is it true that side 2 was originally going to be side 1, and side 1 was originally side 2?

Yeah.

How did that happen?

We made our albums for cassettes because that was our biggest medium. We wanted our albums to pretty much transmit in tapes. They had an A side and a B side. A lot of times what the early record companies made a mistake on is that they never made the sides even. If you don't make a side even, if the second side is longer than the first side, what you have is the kiss of death on the first side, and that's silence.

We were very careful that if side B was 29 minutes and 30 seconds, then we're going to try our best to make side A be 29 minutes and 35 seconds, so you'll get no silence. That was our radio experience. If you hear two seconds of dead air on the radio, you notice it. We don't want no dead air.

It's such a startling way to start your record, though. Obviously, there's a precedent for that with James Brown's live intros and things like that, but when you guys flipped it and made that side 1, was there any thought like, "Are we really going to start our record with some stage banter?"

It was made for live. With the second side, we found a way that would've actually worked, but at the last second of mastering, [producer Hank Shocklee] said flipping the side would make it work better. So, we don't bulls---. We go into it live in concert with Griff opening it up, and we go right into "Bring the Noise" at 109 beats per minute, which was an insane BPM at that time.

Suzie Gibbons/Redferns Public Enemy

What was the process like of incorporating all those vocal samples from speeches all over the album? How did you find and catalog them and figure out what would work where?

I cataloged three rooms of records for Spectrum City, our DJ outfit. My whole job was to conjure up the voices. Again, we didn't want any dead air whatsoever. Even if a record faded and then the next record came in, that was taboo to us. If anything, that fade better happen and that silence better be a microsecond before the next joint. So I was filling those spaces up with interstitials that had words in key areas.

Like with Wattstax. At that time, Wattstax was a concert that by 1987 was forgotten. It was almost like this thing that happened that people didn't even believe had happened — 100,000 Black people inside a stadium checking out the music of the day. I had categorized it for the longest period of time, and when it came time to use it, I was like, "Oh, s---. We didn't take any of the music. We took the live event!" We had our own live interstitials that were put inside It Takes a Nation… and this was adding probably the greatest Black live event of all time into what we considered a keystone, groundbreaking live event that documented hip-hop's next generation.

Speaking of your own live bits you added, after It Takes a Nation… came out, anytime any song my buddies and I were digging ended, we'd be like, "Bring that beat back!"

The influence for that was Gratitude, the live album by Earth, Wind & Fire, [who] were coming off of That's the Way of the World. Their next record was Gratitude, which was live with a lot of that stuff from the previous couple of albums. Gratitude went over big in Black communities.

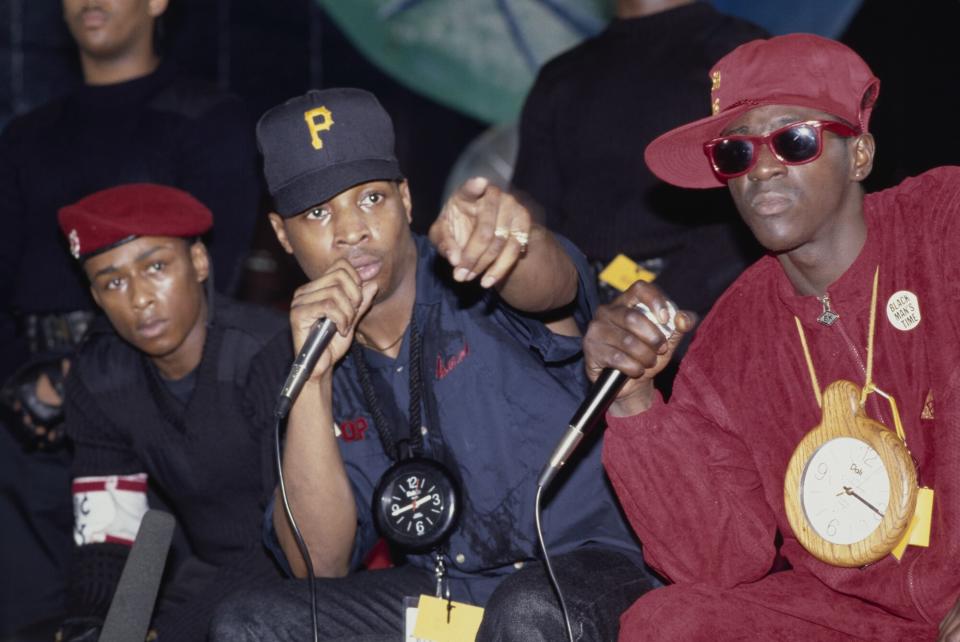

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images Chuck D and Flavor Flav of Public Enemy

I could keep you here all day talking about the lyrics on this album, but do you have a favorite line that still rings true to you in 2023?

Well, I have a lot, but it would have to be "Can I tell 'em that I really never had a gun?" We've lost ourselves in the culture of guns. It's mass nihilism. It's crazy.

My favorite was always the "Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos" opening: "I got a letter from the government the other day. I opened and read it. It said they were suckers." That actually might be my favorite lyric ever.

Yeah, that's a lot of people's favorite. In my prime, people gave me credit for being the first out of the blocks. That came off of the running track. I'm going to try to nail you in the first 15 yards out of the blocks, like boom! "Here it is, bam! And you say, 'Goddamn!'" Or "Yes, the rhythm, the rebel!" Or "Bass! How low can you go?" That became a signature. It's also how Berry Gordy did his stuff at Motown. He said the first 10 seconds better not be playing around.

I think that's one of the reasons I go back to "Night of the Living Baseheads" so much as the song I love the most on this album. It starts with the speech, and then you and the beat just jump in so hard.

The making of that record was so odd because we kind of reduced it, in the words of Rick Rubin. We had a straight-across track with a sample, and then I remember going to [Bomb Squad producer] Eric "Vietnam" Sadler, and I said, "Well, let's erase it from the two-inch." When you erase it from the two-inch, you don't have the crutch of going back to it or unmuting it. So we had no other choice but to fill those empty spaces with what we call cram-sampling. A cram sample is, if you got five seconds of nothing, you got to fill those five seconds up with something that bridges it onto the next beat.

Raymond Boyd/Getty Images Chuck D of Public Enemy

This album is such a leap forward sonically from anything before it with the beats, the samples, and things cutting in and out. It comes across as carefully orchestrated chaos. What was the approach you were going for in terms of cramming in all that stuff?

The first thing Hank looked for is a steadiness of the studio. For Yo! Bum Rush the Show, we used Spectrum City Studios. It was almost like an experience of, "Okay, we're in a spot, but we're kind of trying this place out." And then we recorded "Rebel Without a Pause" at Chung King, which was a Def Jam mainstay and Rick Rubin's go-to studio. The Beastie Boys and Run D.M.C.'s Raising Hell had been recorded there. Then we recorded bits and pieces of "Bring the Noise" at Sabella Studios.

This is where Hank's brilliance comes in, because if Phil Spector was the wall of sound, Hank is a wall of noise — because of his ability to hear the noise, hear through the noise, and then be able to make a pristine mix of it all. Hank wanted to have a place to call his own, which became Greene St. Studio, where Run-D.M.C. did some initial work. So all of a sudden, we began using Greene St. Studio and engineer Rod Hui.

That relationship was a very key anchor point in the creation of It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back. It was a stability and a locality of something that we could call our own that wasn't crowded yet. With the success of Public Enemy and It Takes a Nation… — and later on, Fear for a Black Planet — Greene St. became an impossible studio to book afterwards. Hence, later on, I'm in one studio and then you got Sonic Youth in another studio on the same session, and we're ordering the same food. And then, Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore are like, "Oh, come in. We're doing a song." That's how I did my vocals on "Kool Thing."

Raymond Boyd/Getty Images Chuck D and Flavor Flav of Public Enemy

I saw you live at a few shows around that time — in the tiny 9:30 Club in Washington, D.C. and also at the Capital Centre in Landover, Maryland…

We played at the Capital Centre with the Beastie Boys in April of 1987 and then later came back to play it with the Def Jam tour a day after coming out of Philly, and I was known for saying, "F--- go-go."

Exactly. That made a lot of waves in D.C. We're a go-go town, Chuck.

We came from Philadelphia, which was a raucous takeover, changing-of-the-guard type of gig. And then when we played D.C., we got no response because it was a whole different city. I was like, "How the f--- can Philly be so different from D.C. only a hundred-some-odd miles away?" I was flabbergasted. I was looking at a still crowd without knowing that it takes probably a year for that market, and you got to go through the go-go routes. I just said, "F--- go-go. What the f--- are y'all doing?" That caught some attention, and I had the audacity at the time to be able to say, "Well, you know what, man? Love and hate's the same emotion." I didn't know how it would go the rest of our career, but the next year we came to play D.C., and D.C. was in love with Public Enemy.

I remember at one point during that '88 show you said, "I want all the brothers to stand up and put your fist in the air." And then you said, "I'm not talking to you white people. You can sit down." Which is what I then did. [Laughs] The album is so clearly a message for the Black community, so how much did you guys talk or think about what white audiences were going to make of all this as you started to get more popular and see some more people like that at your shows?

My answer was, "I'm talking to Black." That was our nationalist record. Fear of a Black Planet was pretty much, "Okay, I'm going to include everybody in the mix," but It Takes a Nation… was straightforward: "This is us needing to talk to us, trying to fix us right now." A lot of the people in the Def Jam camp, like the Beastie Boys, brought me in, but who I was talking to was not directly white folks at all. No.

I had white folks all around me. I grew up in Long Island. I went to college and university. I went to a white high school. Def Jam was white. You know what I'm saying? Rick was from Long Island too. We knew how to talk to Black people, even though we were in the middle of white folks, and it was, "Hey, Black folks need this message. White folks are getting messages from everywhere."

I mean, the biggest thing is that we knew everything about white America. They knew nothing about us. Nothing. I knew everything about white America. Everything. I knew more white American history and Italian history and all that than most people who were white and Italian. It Takes a Nation… was definitely a Black narrative — like, "Listen, this is what it is." Of course, white folks are going to pay attention to it, because if they're in their culture, then culture is to seek out and try to find out about as much of what is coming their way as possible. That's what that was.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images Chuck D of Public Enemy

As a teenager, this was the album that got me to go read The Autobiography of Malcolm X. You were educating people, even if they were not the audience you were speaking to.

We were asked to challenge Black people. We were like, "All right. Your white friend knows more about you than you know yourself, so you're volunteering yourself to slavery. Once somebody knows more about you than you know, what are you doing?" Really, It Takes a Nation… was a call to arms and a challenge.

How did you settle on It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back as the album title?

It was actually a lyric in "Raise the Roof," which was on Yo! Bum Rush the Show. The original title of the album was going to be Countdown to Armageddon. But there was an article from Toronto, Canada, and the editor of that particular music magazine actually titled the article "It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back," talking about one of the lyrics from "Raise the Roof." So I had the article and I come back to our headquarters. When me and Hank saw "It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back," we were like, "That's a long-ass title, but it sticks out. If you are going to use something long, why not?" That's it. We changed it. "Countdown to Armageddon" then became the name of a track on the album.

And the cover art and photo by Glen E. Friedman are so arresting — no pun intended.

Our art direction had to definitely be on what we had centered our intent to be, but everybody was coming to the table. Glen had enough background where he knew what was punk and what wasn't, and we knew what was rap and what wasn't. We could take a little bit of this or a little bit of that and figure out how to come up with something that would depict the attitude along with how we sounded with one or two images.

The cover was very significant. It Takes a Nation… was actually knocking that posse shot down to just me and Flavor, and the group was on the back. And then by the third album [Fear of a Black Planet], no group at all. But we saw a tendency in Black albums that every single Black record had to have everybody looking for validation on the cover. If the group had eight people on it, everybody had to be on it. Anybody left out, then it's f---ed up. Hank railed against that. It's like, "Listen, man, the concept of the record needs to stand out, not just everybody's there for a vanity shot."

The jail shot was in midtown Manhattan. It was cold up in there. We were also trying to get a cover for "Don't Believe the Hype," and what we did is that whole multi-shot with the camera negatives at that particular time. That camera roll ended up being iconic in itself. But yeah, we shot it to make those visual statements.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images Public Enemy

Any thoughts on this album's themes in terms of where we stand today, 35 years later?

Well, it makes it easier for me to travel the world and be able to say, "Okay, this is a theme I think we need to hit at now." Like mass incarceration. "Don't Believe the Hype" actually fits right now. We're talking about challenging misinformation. "Bring the Noise" is like, "Hey, we ride limos too" — respect the genre of hip-hop and rap music as important as anybody else out there or any other genre. I mean, the "beat is for Sonny Bono and Yoko Ono and Run-D.M.C. and R&B as well" — I was just making those statements inside the grooves, and it was very important that we do that. I actually haven't heard the album in a while. Maybe one day this year I'll listen to it.

Sign up for Entertainment Weekly's free daily newsletter to get breaking TV news, exclusive first looks, recaps, reviews, interviews with your favorite...stars, and more.

Related content: