Choosing an art path: Join Alberto Escamilla in celebrating his legacy Sunday

Borderland artist Alberto Escamilla’s life has been shaped by chance and choices.

On Sunday, Sept. 24, El Pasoans can join him in celebrating the art legacy those decisions have created.

An exhibit, “Forty-Five Years of Art,” will celebrate Escamilla’s career. The free event will be from 2 to 5 p.m. at the Woman’s Club of El Paso, 1400 N. Mesa St. Escamilla will speak at 3 p.m.

Pianist Esequiel “Zeke” Meza will perform. For more information, call 915-474-1800 or visit https://www.albertoescamilla.com.

Visitors to his show will see exclusive work.

“Hanging on the walls are 11 paintings from my private collection, which are not for sale,” he said in an email. “These paintings are circa 1970s to 2005.”

He added, “I will have my recent paintings that are for sale, along with some of the items we sell in our gallery in San Elizario. The sizes of the paintings are from 5″ x 7″ to 30″ x 40.” This event is a one-day reception and exhibit in celebration of my 45 years as a professional artist.”

Escamilla, who was inducted into the El Paso Artists’ Hall of Fame by the International Association for the Visual Arts on Oct. 22, 2004, credits his wife for much of his success.

“My wife Rachel Braunston Escamilla has been very instrumental in influencing my career,” he said. “From the moment we met on a blind date on New Year’s Eve 1981, I learned she loved the arts as much as I did. She has been so encouraging in my journey in the art business. She is my muse, confidant, business manager, friend, soul mate and so much more.”

His work also can be seen at Escamilla’s Fine Art Gallery, 1445 Main St., in historic San Elizario, Texas. The gallery’s office phone number is 915-851-0742. It is open from 12:30 p.m. to 4:30 p.m. Wednesday through Sunday.

Escamilla’s brush with college basketball greatness had its start in a small Texas town around 305 miles southeast of El Paso.

“This all started when I attended high school in Sanderson, Texas,” Escamilla said. “I was a star player on their basketball team, having been in regional playoffs.”

Escamilla said his basketball coach knew legendary basketball coach Don Haskins when he was a high school coach.

He said that after Escamilla graduated from high school, his coach suggested he go to Texas Western College, now the University of Texas at El Paso, because Haskins was now the coach there “and I should go in as a walk-on to try out for the basketball team. I did and was accepted into the freshman team.”

The members of the freshman team of 1962 went on to become the national basketball champions in 1966, Escamilla said.

More: El Paso Museum of History exhibit highlights cultural changes following Mexican Revolution

But Escamilla chose a different path.

“Since I was on the freshman team, I was actually under coach Moe Iba. So, he was the one I told I was leaving the team to pursue an art career. He said it was my choice, but he mentioned that I had already survived the first year.”

That decision came back to haunt him a few years later.

“In 1963, I made up my mind to drop basketball and concentrate on becoming an artist. If I had known the future of the basketball team, I would have stayed on the team,” he said.

“When I was on a train going home in March 1966 and listening to the NCAA Championship Game on a transistor radio, I learned the Texas Western basketball team had won the national championship. I thought to myself, ‘What have I done? I could have been there with them.’”

However, he said, “when you get older and look back, you realize why things happened the way they do.”

Leaving team led to him saving his family from flood

The decision led to Escamilla saving his family from a deadly flood.

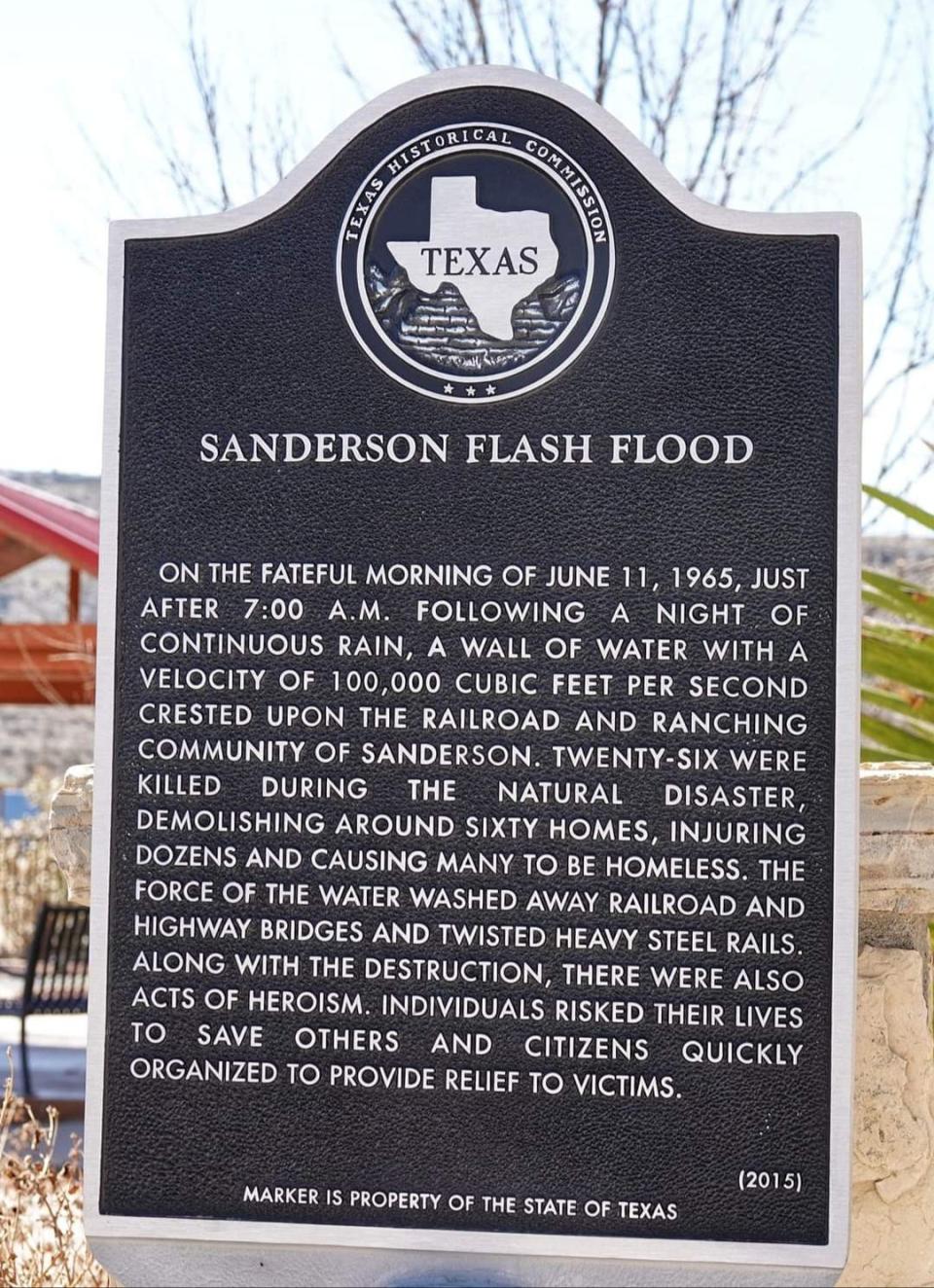

“Sanderson, Texas had been receiving heavy rain for several days, and on June 11, 1965, it got worse,” Escamilla said. “I was in Sanderson for the summer working at a construction site. This particular morning upon getting up to go to the work site, I noticed the Sanderson Canyon river had overflowed, and I could see the water was rising fast due to a cloud burst.

“Sanderson is in a canyon, and I could see the water coming down very fast. I gathered up my grandmother, my mother, sister and aunt and put them in the pickup I was using, but my grandfather did not want to leave the house. I had to force him to get into the pickup with the others,” Escamilla said.

“As we drove away one block up the hill, we heard the loud noises of when the floodwaters burst in and washed away everything along Main Street, which included my parents’ home. If I had not been there, they would have been washed away in the house.

“As I got older, I realized this was the main reason I did not stay with the basketball team,” Escamilla said. “My uncle was one of 26 people who drowned as he was driving a tow truck trying to get to his family’s home to rescue them. His body was never found.”

Being free to leave the El Paso campus during the college break had brought Escamilla home in time to save his family.

Leaving the team also brought Escamilla a successful art career.

“I have always liked coloring and drawing as far back as I can remember,” he said. “When I came to Texas Western, one day I saw some students sketching on drawing pads on the lawn in front of Cotton Memorial, which was the art department at the time. I stopped and asked them what they were doing and they advised they were part of a drawing class. They suggested I go inside the building and inquire about the art program. I then learned art could be pursued as a career.

“Right then, I decided this was what I wanted to do, become an artist,” he said.

“When I bought the material for my first art class and had to go to the bookstore to buy the supplies, it was an eye opening experience. I had no idea there were so many various types of materials to become an artist. Most of the students at the time were from larger schools who had prior art training and I did not have any type of art experience. At one time, my professor asked me if I wanted to pursue another career as I was such an amateur.”

Escamilla didn’t let the professor’s doubt deter him from his art journey, which also ultimately led to physical pain.

Physically suffering for his art

“I did not realize that being an artist would be detrimental to my health,” he said. “Because of the many years of painting, the ulnar nerve of my right arm was damaged, and I had surgery to help relieve the pain I was experiencing. My fourth and fifth fingers have never been the same as they tingle and hurt so I cannot use them like I used to when I paint.”

He added, “I had to find another way to use my brush in order to continue painting, and this has slowed down my production time. Also, because of the position I use when painting, I developed cervical spinal stenosis and had to have surgery on two of my discs. This also hampered my painting, and I had to adjust the way I paint. This surgery had to be done through my throat and it has hampered my swallowing and talking.

“I am 80 and now having vision issues, which also slow down my production. I’ve got a torn retina, have macular degeneration and receive an injection every six weeks in one eye,” he said. “I have learned to adjust to the various medical issues to keep on doing what I love — painting!”

Friendship with Cormac McCarthy

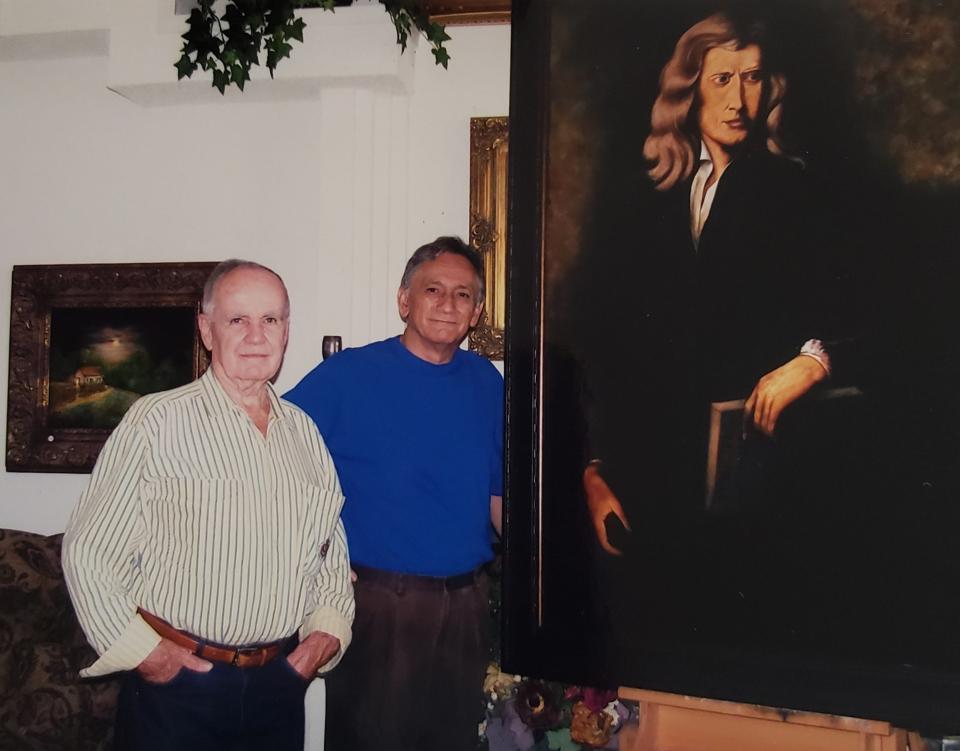

Through his art, Escamilla became good friends with renowned author Cormac McCarthy, who lived in El Paso for a time before eventually moving to Santa Fe, New Mexico. McCarthy, one of the nation’s most beloved authors, died June 13, 2023, in Santa Fe, New Mexico, at the age of 89.

“I met Cormac McCarthy when he asked the curator of a museum exhibit if he could be provided with my contact information,” Escamilla said. “He had seen two of my paintings, which were in the exhibit, and liked them and wanted to meet the artist. We became friends and he would sometimes come over to our home for dinner. Through the years he purchased two dozen of my paintings. He also commissioned several paintings, one being of his grandfather.”

Escamilla added, “One of the paintings he purchased was ‘A Tribute to My Grandmother.’ One night when he visited, I had just finished this painting and he said he really liked that painting and wanted to buy it. My wife, Rachel, and I discussed whether to sell this one as it had a special meaning behind it.

“My grandmother (Ester Paz) had told me stories through the years on how her family had to flee Mexico during the Mexican Revolution and this painting was a tribute to her. I had done a series of Mexican Revolution paintings for an opening of a Mexican Revolution musical production that was to be held at the Chamizal. I had gone through some black and white picture prints of the Mexican Revolution at UTEP and came across a picture of these people crossing the desert and instantly pictured my grandmother’s story, so I painted it.

“Cormac insisted on wanting to buy this painting as his books depicted the Southwest area, as did this painting. So, by the end of the evening, I decided to sell it to him. It is our number one selling image.”

Escamilla said: “When I first met Cormac, I did not know he was going to be a famous author. He was a very private person. I appreciated his friendship as he was very down to earth. Our conversations were about history and technical stuff as he enjoyed working on his pickup truck. We would go to Barnes and Noble often and other bookstores. He would ask how his books were doing.

“When I was accepted to show my work in New York and told Cormac about it, he got so excited for me, he went outside and did a cartwheel from the excitement. During one of our conversations, he advised — try to keep as much of yourself and success private. Let others come and ask, make yourself look like a mystery.”

Escamilla recalled: “Several times Cormac and I would have a late lunch at Luby’s cafeteria on Mesa. One day he said: ‘Alberto, look at the people just walking by us and not knowing they just walked by the world’s most famous author and most famous artist.’

Escamilla said, “Through the years, Cormac did not want his other artist friends to know he was collecting my work as he did not want to hurt their feelings.”

However, “After his last commission, which was a portrait of Isaac Newton, that was to hang in the conference room of the Santa Fe Institute, Cormac said it was now OK for us let it be known he was a collector of my work. Cormac wrote my artist statement and I have the actual written papers where he composed it. I have various memorabilia of our times together.”

Escamilla’s faith has brought him a greater sense of accomplishment: “bringing the beauty of God’s world through my art for 45 years.”

It also has given him a life without regrets.

“None — would do this all over again,” he said. “I have had a blessed journey because God has been the driver and all the glory is to God.”

This article originally appeared on El Paso Times: Join Alberto Escamilla to celebrate legacy at Woman’s Club of El Paso