Our children must learn our history, especially about killings of Harry and Harriette Moore

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I won’t pretend to understand the reasoning behind the critical race theory. I won’t pretend to understand why some people think it is wrong to teach our school children — of all races and nationalities — the true history of race in America, but it’s OK to remember the Alamo.

Slavery is a dark blot on our country’s history. So is lynching and segregation and denying the right to vote. And the way Native Americans were treated. But it is our history. We remember because we want to do better. We remember because we don’t ever want it to happen again.

Yet, as much as some people don’t want to remember, we see history repeating itself nearly every day in the seemingly police-protected killings of innocent Black people. Because we don’t want to remember and learn from our past mistakes, we see new events that will mar our country’s future history, such as the big lie about a stolen presidential election. Some even have said the storming of the nation’s capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, never happened, even as millions of us watched the insurrection as it unfolded live on national and worldwide television.

I am a person who has lived through the atrocities of segregation and Jim Crowism. Still, I don’t blame my white friends for the slave ships that brought thousands of Africans to these shores. I don’t blame my white friends for the crimes against my people that were committed by some of their foreparents. While we are at it, should we also blot out the story of how this land was taken from the American Indians, who were the real Native Americans? To blot out the truth means that we will forever live a lie.

While there are those who don’t want to remember, or don’t want their children to know their country’s history, it pleases me to know that Westminster Academy in Fort Lauderdale will stand up and be counted for what is right. Starting this school year, the private Christian school has included in its regular school curriculum the story of Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore, a Black husband and wife team who lived in Mims in Brevard County, and who were pioneers in the civil rights movement and the movement’s first martyrs.

“As history is being told, our school wants fair representation for both Black and white students, “ said Jeff Jacques, dean of spiritual development at Westminister. “That means we wanted to share the history of a series of events that happened here in Florida. The Moores’ story is one of them. Our objective is to educate our students on the history of the state and whatever we present to our students we want it to be concrete, fair and accurate. The story of the Moores fits that description.”

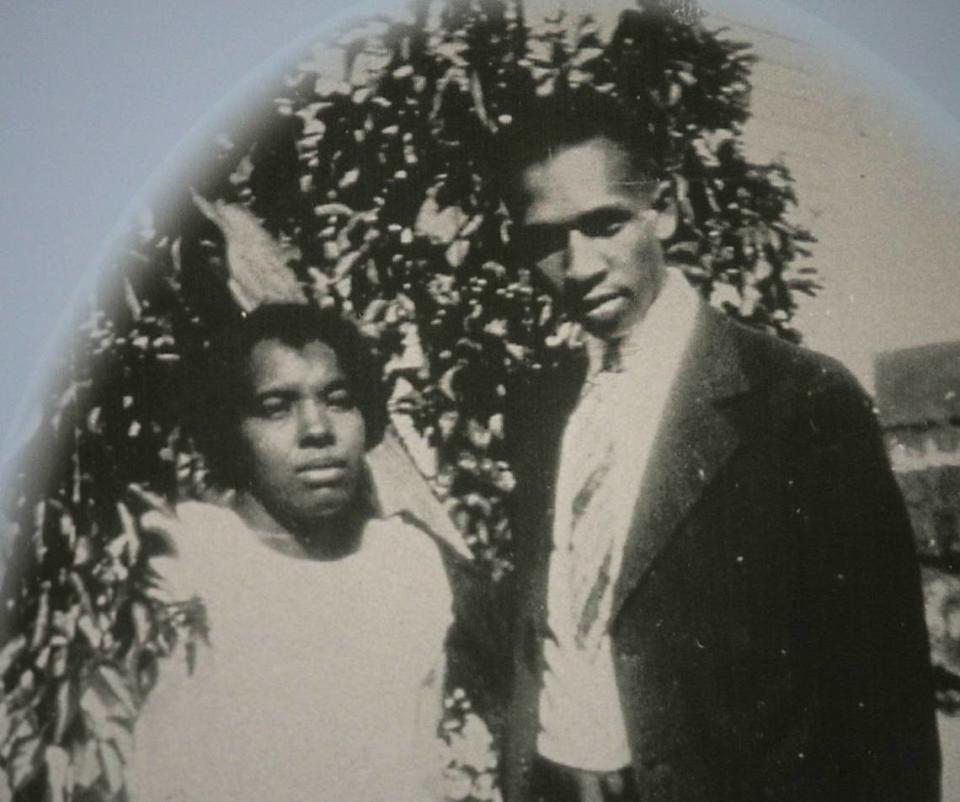

Until that fateful Christmas night in 1951, Harry and Harriette Moore were probably not very well-known outside of their home in Mims, located just north of Melbourne on Florida’s East Coast. Moore and his wife had just returned from celebrating Christmas and their wedding anniversary at the home of relatives.

It was a cool and foggy Christmas evening and the Moores had just settled in for a peaceful night’s rest when, about 10:20 p.m, a bomb exploded directly under their bedroom in their small shotgun-styled house.

Harry Moore died en route to the hospital, about 20 miles away in Sanford, in a car driven by his brother-in-law George Simms. Harriette Moore would suffer nine days, before joining her husband in death. Their daughter Anna Rosalea, who was home with her parents that night, was also injured in the blast. Another daughter, Juanita Evangeline, was on her way home for the holidays and missed getting injured or killed.

Both school teachers, the Moores were the first true civil rights activists of the modern civil rights era in Florida. He organized the first Brevard County branch of the NAACP in 1934 and later became its president.

During those early years of Florida’s NAACP, Moore organized chapters throughout the state, and in 1941, he was named president of the Florida Conference of NAACP branches. He later formed the Florida Progressive Voters’ League and served as its executive director. The league was instrumental in helping register over 100,000 Black voters in Florida.

In those days, Moore was known as an “uppity Negro.” Because of his civil rights work, his fight for equal pay for Black teachers, and his speaking out against lynching and other racial violence against Blacks, he and his wife both lost their jobs as school teachers. In February, the Brevard School Board passed a resolution honoring the Moores, acknowledging their unfair firing by the school board in 1946, and called for a social studies curriculum to be developed around the Moores.

On June 19 — Juneteenth — Northwest Seventh Street between Northwest 27th Avenue and 31st Avenue in Fort Lauderdale was renamed for the couple.

The Harry T. and Harriette V. Moore high school curriculum is based on the movie about their life, called “The Price for Freedom,” written by John DiDonna in association with Walter T. Shaw, producer. The movie is scheduled to open in late 2022.

The high school curriculum, written by Erica Fix, a high school teacher from Michigan, includes lesson plans that may be used together or alone in high school U.S. history or English classrooms, Shaw said.

“I went to her and told her that this story should be taught in our schools. I gave her the book and paid her to write the curriculum,” Shaw said. He said the movie and the curriculum were inspired by Gregory Marquette’s book, “The Bomb Heard Around the World.”

I asked Shaw why he wanted the curriculum placed in schools.

“This is a story that everyone — especially our school children should know. We should never forget our history, where we came from. The children have a right to know,” he said.