Charlie's Angels failed because the franchise era as we know it is changing: Opinion

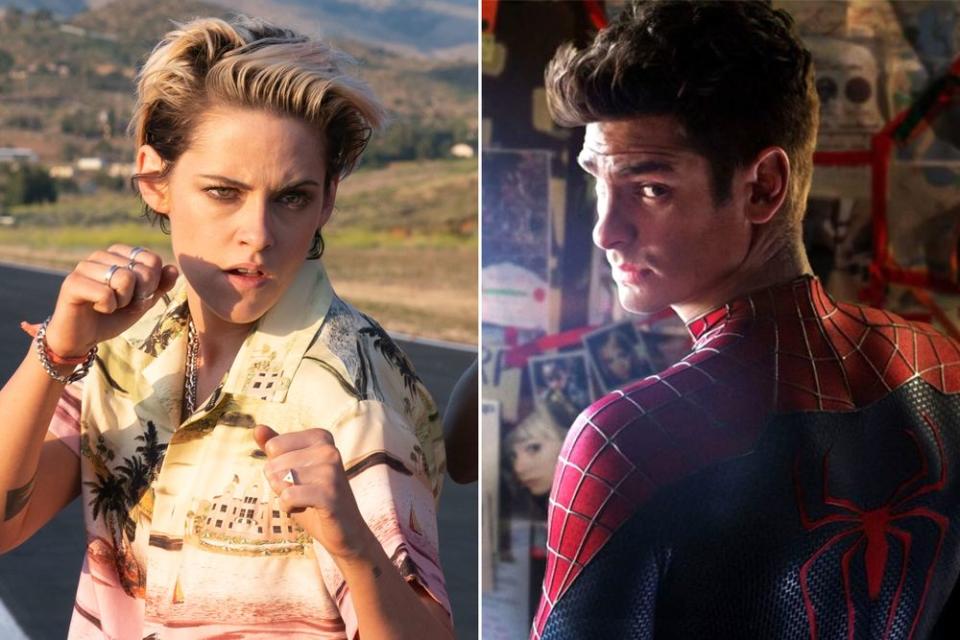

Charlie’s Angels isn’t terrible, and there are some terrible movies that gross a billion dollars. So why did the Elizabeth Banks-helmed reboot, featuring a vibrant Kristen Stewart, fail so miserably at the box office?

There are some obvious problems, flaws worth bean-counting for Sony, which released the film. Stewart was a generational figure for Twilight kids. She spent the rest of this decade minting hipster cred in Europe and Indieland. This new Charlie’s Angels could have been her thrilling reintroduction to the mainstream — but Stewart is the comic relief, her character given less proper plot than anyone in the main ensemble. The other leads, Ella Balinska and Naomi Scott, aren’t yet established stars. It was an event, in 2000, to see Drew Barrymore, Cameron Diaz, and Lucy Liu together in the first Charlie’s reboot. (Liu was arguably the least famous, I guess — and yet, everyone back then knew she was blasting off Ally McBeal, possibly the single most-discussed TV show of the ’90s that no one ever discusses today.)

In fact, Stewart’s Sabina has less of an arc than the character who — in Charlie’s Angels lore — should be a supporting figure. Bosley is, theoretically, the Person Who Gives The Angels a Mission. In this 2019 variation, though, Bosley is a collective rank most clearly embodied by a character played by Banks herself.

Sometimes, the best thing you can hope for with a franchise reheat is the bare hint of personality, a feeling that a filmmaker is finding something uniquely them in the clanking machinery of 20th Century Intellectual Property. One utmost recent example is what Ryan Coogler brought to Black Panther, reframing the comic book iconography around a tragic secret origin in the director’s own native Oakland (not to mention the movie-heisting performance from Coogler’s frequent onscreen collaborator Michael B. Jordan).

And Banks, to her credit, gives her Charlie’s Angels some eccentric flourishes that feel almost biographical. Her character, we find out, is the first-ever Angel promoted to Bosley-hood — metaphorically, an actress who became a director. The hand-off from Patrick Stewart’s Bosley to Banks’ Bosley is rich with gendered meaning, especially given the final-act twists which prove that some Bosleys are anything but angelic.

To give Banks more credit, she clearly realizes that the whole concept of Charlie’s Angels looks archaic, even regressive, today. The original series lives in cultural memory as an Aaron Spelling slice of ’70s cheese, built around the central idea of women following orders from a powerful absent man. (Note the possessive in the title: These angels belong to him.) Unlike the 2000s movies, which gloried in their goofery, Banks’ film clearly wants to break new ground for the franchise. She gives herself a few world-weary lines, of the “Women are always hungry” variety. There is a ridiculously sincere montage of young women around the world, united in sisterhood. The Townsend Agency itself has become a global sorority. Even the advertising for the movie is telling. “Sworn to Secrecy, Bound by Sisterhood” — those words don’t really have any obvious relation to the plot, and yet those sentences seem to speak hidden volumes about the last few years. (Hell, it could practically be the tagline for Bombshell.)

I leave it to much deeper thinkers to analyze precisely what kind of feminism this new Charlie’s Angels represents. There’s a suspicious elitism underpinning the collective spirit, a sense that you’re watching an elaborate advertisement for the Wing. Still, the film saves its shiftiest twist for the very end — ***SPOILER ALERT*** — when we learn that Charlie isn’t a man at all. She’s a woman, using a John Forsythe-a-like voice modulator.

Is this new Charlie some former Angel, a woman in a man’s world who has kept the original Charles Townsend “alive” in fear of losing misogynist clients who wouldn’t trust a woman? Or, does the subterfuge go deeper: Has the Townsend Agency always been secretly female-run, its founder forced into the shadows by a society that, as Stewart’s Bosley says at one point, wasn’t always ready for the Angels? Basically: Is this a Weekend at Bernie’s or a Victor/Victoria?

Who knows? One important lesson of this new Charlie’s Angels, maybe, is you really can’t save the good stuff for the sequel. Banks has sounded admirably pithy about the movie since its release, at one point saying: “You’ve had 37 Spider-Man movies and you’re not complaining.” The Spider-Man comparison is a smart one, and I’m not just saying that because I think the recent run of Spidey films runs meh-to-bleh.

When I think about all the unrealized promise of the end of this Charlie’s Angels, I remember the truly embarrassing Amazing Spider-Man duology from earlier this decade. That 2-part origin story kept teasing big showdowns ahead, ending two straight films with identical “See you next sequel!” mystery-man cliffhangers. This new Charlie’s Angels is, tragically, another origin story — the Angels themselves are getting to know each other gradually, so it’s only in the final scenes that the movie gets to conjure up the party vibe it’s looking for.

The big issue, I think, is that Banks’ Charlie’s Angels so clearly represents the poor instincts of the modern franchise era — an age, by the way, that is hopefully coming to a long-awaited end. There’s been a lot of talk that the Angels flop comes fast on the heels of box office failures for the Shining sequel Doctor Sleep and yet another terrible Terminator movie. You could also throw in Men in Black: International, which successfully squandered Tessa Thompson and Chris Hemsworth — and we should not forget Dark Phoenix, one final pre-Disney flare of campy Fox mutant cinema (at least until anyone finally sees New Mutants).

How could all these franchises fail, while Disney keeps printing money off ’90s childhoods and comic book concepts from half a century ago? What unifies them all, I think, is a secretly conservative angle on their own iconography, an unwillingness to do anything new (beyond adding terrible new digital effects). The new Terminator revolves around a bad guy who’s obviously just a combination of past Terminator bad guys. Dark Phoenix is a do-over for a comic book story arc that already died in another bad movie. Doctor Sleep has its fans, but the film is structured around an oddly shameless bait-and-switch, clashing flashbacks to the Overlook Hotel into a brand new story about nefarious telepaths with terrible hats. Men in Black: International is the worst and most telling comparison point here, squeezing the particular charms of Thompson and Hemsworth into somebody else’s clothes. There’s a similar feeling in Charlie’s Angels that Stewart and Banks are fitting their eccentricities into a format, when they should be exploding it.

Marvel sure isn’t perfect, but that cinematic universe keeps self-renewing, tearing down some franchises to make room for newer central figures. And the moment feels right for something like Patty Jenkins’ upcoming Wonder Woman 1984, which promises to take the title character (who already starred in three movies!) into entirely new timespace surroundings. Look, it doesn’t always have to be philosophical-societal brain surgery: Sony’s own Jumanji revival featured a new star lineup and a conceptual nudge forward into video game tropes. It’s a frustrating lesson, like every Hollywood truism: When you’re being unoriginal, it still helps to be original. The biggest bummer about the new Charlie’s Angels is the knowledge that you’re watching talented people speak with somebody else’s voice.

Related content: