Charles Busch Is Ready to Dish, So Watch Out!

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Actor. Writer. Filmmaker. Playwright. Drag icon. These are just a handful of the titles Charles Busch has claimed over the course of his celebrated—and singular—entertainment career, which has taken him from Broadway to Hollywood (with more than a few “rat-infested basement” theater performances in between). While he has carefully crafted his role as a self-described “male actress,” and has a complicated relationship with being called a “drag queen,” “raconteur” might be the more befitting descriptor for the Tony-nominated creator of The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife.

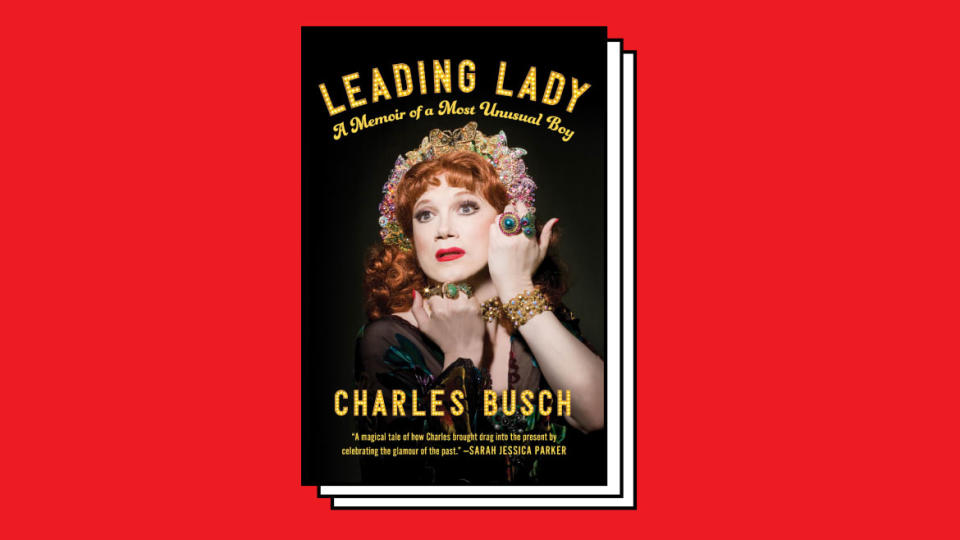

While Busch has been telling stories for nearly half a century now, they’ve rarely been as personal as the ones he’s sharing in Leading Lady: A Memoir of a Most Unusual Boy, which traces his journey from a motherless boy in Hartsdale, New York, to the so-called “godmother of drag.”

Busch is one of those rare humans who is unafraid to live life on his own terms, making up the rules as he goes along—then changing them as he sees fit. But even readers who are not familiar with Busch’s signature camp, which can be seen in plays-turned-movies like Die, Mommie, Die! and Psycho Beach Party, will find his endless series of personal anecdotes affecting and hard to put down. In Leading Lady, Busch doesn’t hide anything as he shares random moments from his extraordinary life—some of them heartbreaking, many of them hilarious, and others both at once.

Busch heartbreakingly shares how, in the summer of 1962, his life was forever altered when his mother died suddenly.

On June 21, 1962, when Busch was just 7 years old, his mother—a typically reserved woman—worked up the courage to confront their neighbors about their dog, which regularly ran loose in the neighborhood and had adopted the Busches’ front yard as its favored toilet. While standing on the neighbor’s, she suffered a heart attack and died before an ambulance arrived.

Liza Minnelli Turns 75. Her Famous Friends Have Some Tales to Tell.

“I didn’t cry,” Busch writes of the surrealness of that day. “I watched the characters in the movie. Daddy pulled me over to him and wrapped his arms around all of us. Crushed in that tight embrace, I wondered, What happens to us now?

“Was that the first time I came up with that question? It’s what I wonder after any moment of tragedy or joy. An opening night and a rave review is read aloud; everyone cheers and embraces each other with abandon. I stand apart, watching the others and silently wondering, What happens to us now?”

Busch quickly adopted Judy Garland as his mother figure—even though they never met.

“All my life, I’ve been in a search for a maternal woman whose lap I could rest my head on,” Busch confesses from the get-go. It’s that desire that fuels much of the narrative, as well as the trajectory of Busch’s extraordinary career. And Judy Garland became the first in a long line of women who he allowed to fill that maternal role for him, though he only knew her from her movies.

“I wasn’t allowed to attend my mother’s funeral at Ferncliff in June 1962. Being seven years old, it was felt that I was too young,” Busch explains. “Around the time of my mother’s death, my father told me that the neurasthenic lady with the thrilling singing voice we were watching on television was Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz all grown up. From that point on, Judy Garland became a mother figure to me—she even had a son, Joey, who was exactly my age. The image of Judy hugging and kissing her little boy was a powerful one. When she died, there was no question that I’d cut school and join the throng bidding Judy farewell. I hadn’t been at my mother’s funeral, but I would see Judy lying in state.”

Garland passed away on June 22, 1969, almost seven years to the day that Busch’s own mother had died. It’s estimated that as many 1,500 mourners showed up to Frank E. Campbell’s, a.k.a. the funeral home to the stars, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. “We were ushered into the chapel, where we saw Judy lying in a glass-covered white coffin, a soft pin spot providing illumination,” Busch writes. “It was difficult accepting that the doll-like figure on display was Judy Garland. She held a slim prayer book in her hands. I remember thinking that a hand mic would’ve been more appropriate and somehow less kitschy. My companion muttered, ‘They’ve got her hair all wrong.’ Her hair was teased and sprayed, similar to how she’d appeared on her 1963-1964 CBS TV series, not the casual contemporary style we’d seen in her last photos in London. How odd that after a lifetime of tour de force performances and volcanic offstage emotions, she was now an inanimate object to be studied with cool objectivity.”

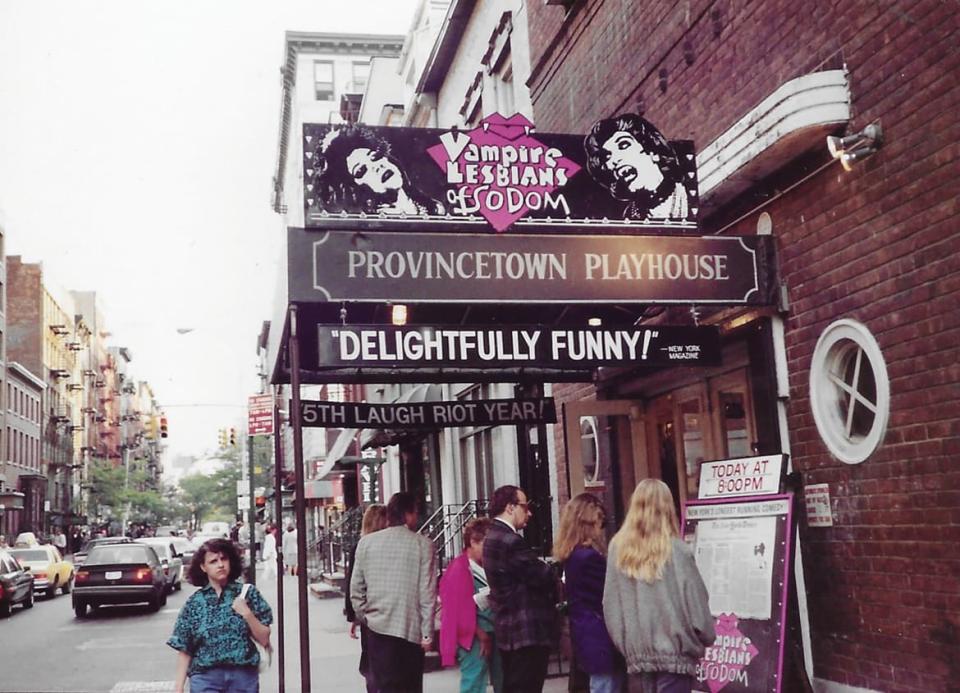

Vampire Lesbians of Sodom at the Provincetown Playhouse

Busch spent a memorable Seder attempting to out-act Angela Lansbury, Sarah Paulson, and Cherry Jones.

Over the years, Busch spent many a Seder with Barry Kohn, the one-time allergist who inspired Busch’s Tony-nominated play The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife. While Busch appreciated that Kohn and his wife, Brina, used an abbreviated version of the Haggadah from which everyone at the table read a passage, “it still seemed a chore” according to Busch… until that one year he turned it into an acting challenge.

Barry had recently befriended Angela Lansbury, who had made a long-awaited return to Broadway after 20 years and was starring in a Terrence McNally play alongside Marian Seldes, yet another stage great. Busch jokingly suggested that Barry invite the pair to Seder, which the host thought was a splendid idea. “It was a small group: Barry; Brina; Angela; Marian; [my partner] Eric; the actress Cherry Jones and her partner at the time, future Emmy Award winner Sarah Paulson; and me. Angela confessed that this was the first Seder she’d ever attended,” Busch writes. “We all sat at the table and began reading from the ancient text that told of the Israelites’ escape from slavery in Egypt.

“Suddenly, it hit me that I was acting with Angela Lansbury, Marian Seldes, Cherry Jones, and Sarah Paulson. I felt pressure to give a performance up to the standards of this estimable company. It was spellbinding hearing them read with their distinctive voices, particularly Angela with her bright Anglo-American accent and Marian in her low cathedral-like whisper. You would’ve thought they were co-narrating a program on the History Channel. When it came around to me, I made every effort to enunciate perfectly and read with emotional expressivity. I thought I was doing very well.

“When I finished, Eric hissed in my ear, ‘I can’t believe you’re reading the Haggadah as Joan Crawford.’ I whispered back defensively, ‘I’m giving it vocal color.’ As each guest took their turn after me, I was competitively flipping through the small book searching for my next passage and thinking, My part stinks. I can’t do anything with this. When at last it was my turn again, I employed every bit of vocal virtuosity to make something of my dreary lines. This time Eric whispered, ‘I never knew the word ‘Jew’ had so many syllables.”

Busch has a complicated history with the term “drag queen.”

While “drag queen” is a term that gets thrown around regularly these days, from politics to pop culture, Busch writes that he’s of “an older generation of performer who bristled at those words. Actually, ‘bristle’ is too mild a description. We became downright unhinged. When that term was applied to us, we felt we weren’t being taken seriously as writers and actors. In days of yore, ‘drag queen’ implied someone dressing up for the outrageous fun of it, possibly having a drug and alcohol problem and a distinct lack of professional behavior.”

Though Busch and many of his peers attempted to come up with alternative terms for the artform they were perfecting (“gender illusionist” was a particular favorite), he now believes that “Perhaps it was disingenuous of me and my colleagues to refuse to acknowledge the profundity of what creating art through a female persona truly meant to us. We demanded instead that it be stated without any ambiguity that dressing up in women’s clothes was strictly a professional choice. I read old interviews I gave where the subject came up and I’m mortified by my glib, evasive responses. ‘I’ve got great legs and I know what to do with them.’ I wanted to be regarded as an actor who just happened to specialize in playing female roles, not as a psychological case of alter ego possession à la Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde.”

For Busch, portraying female characters is not about the visuals.

Ultimately, Busch concludes that “I belong to two worlds: the theater and the drag community, and I’m proud that both claim me as their own. Embodying a female character has been a major part of my creative life. I will not dismiss or belittle it. And I can’t easily separate the lady from the gentleman. The lady is not simply an adopted theatrical persona. Although I’ve taken great pains to create a feminine illusion on stage and film and I enjoy all that this entails, the paraphernalia of drag is not necessary for my own belief in the women I play. I’ve performed feminine roles on radio and in staged readings without costumes. It’s not about visual transformation. To go from male to female is as effortless for me as walking from one room to another.”

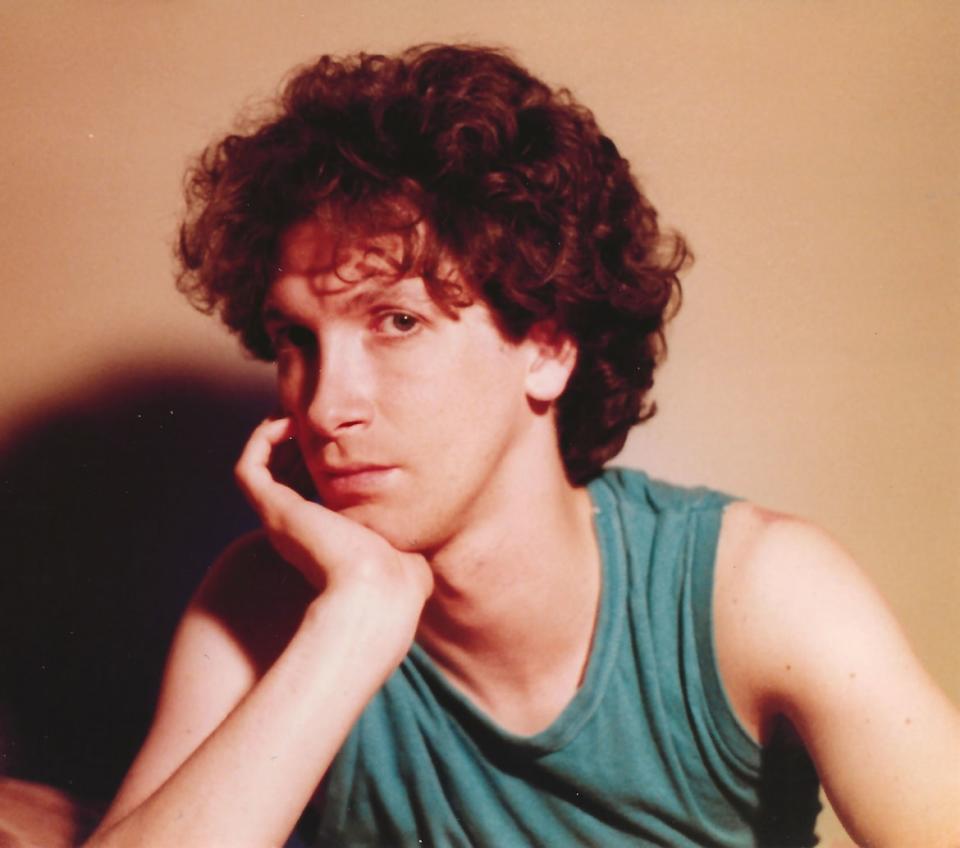

Charles Busch in 1977

Busch had a lot of trouble dying on Oz.

Before there was The Wire or The Sopranos, HBO had Oz—a gritty prison drama that intrigued Busch. After making an offhand comment about how interesting it must be to work on a show like that, Busch found himself in a meeting with series creator Tom Fontana. Shortly after that, he was offered the role of Nat Ginzburg, whom Busch described as “a well-educated, articulate drag performer who in a fit of pique threw acid in another queen’s face. Once in prison, he was enlisted to seduce an elderly retired mob boss and smother him with a pillow. That bit of mischief landed him on death row.”

The character proved to be popular with fans, so was brought back for a second season. “As my second season progressed, the other prisoners on death row were executed, one by one,” Busch writes. “I’ve neglected to tell you that Nat Ginzburg also had full-blown AIDS. Between his advancing illness and being condemned to death by a judge and jury, my prospects of returning for a third season didn’t look promising. In each successive episode, it was evident from the way the makeup man was applying more and more dark shading under my eyes that my days on Oz were numbered. If I was to be written out, I was hoping to leave in an exciting, memorable way, by lethal injection or, better yet, the gas chamber.”

What Busch and Fontana ultimately came up with was even better: series regular Rita Moreno, who played Sister Pete, would paint Nat’s fingernails and prepare him for his walk down death row. But the walk would never happen, because Nat died the night before his scheduled execution. “The day arrived for what I’d hoped would be my epic farewell to Oz,” Busch writes. “Rita and I played our nail polishing scene. It was filled with great dramatic opportunities for Sister Pete, and EGOT winner Rita Moreno certainly made the most of them. We broke for lunch. When we returned to the set, I lay down and played dead. The camera slowly panned over my serenely composed visage and then moved to the group of prison personnel.

“We did the first take and the assistant director yelled, ‘His eyes were twitching.’ I had no idea. I apologized to everyone assembled. Before we did a second take, Rita came over to the bed and whispered, ‘Honey, here’s a trick I learned during my early days at Fox. Before they call ‘action,’ close your eyes tight for five seconds, then relax them. Your eyelids won’t twitch.’ I gratefully took her advice. Take Two and, again, the assistant director shouted, ‘What are we gonna do? His eyes were twitching.’ I was getting anxious. Things had to move quickly on Oz.

“This time my friend BD Wong, who played the priest Father Ray Mukada, came over to my cot and whispered, ‘Here’s a trick I once learned. Open your eyes wide for five seconds before they call ‘action,’ then close them. Good luck.’ We did a third and an unheard-of fourth take and my eyelids were now blinking out of control like oranges and lemons in a slot machine jackpot. The director of photography looked ready to put me out of my misery for real. The last shot of Nat Ginzburg ended up being a quick pan over his dead face, the focus swiftly switching to linger on the mournful mugs of Sister Pete, Father Ray, the warden, and the guards.”

Busch, sad to see his time on Oz end, sent off a quick letter to Fontana suggesting that “What if Nat Ginzburg had a twin sister named Natasha, played by me of course, who under another name seeks revenge by infiltrating the walls of Oz by becoming a prison guard? Tom’s a lovely but terribly busy man, so there could be any number of reasons why he never had a chance to get back to me.”

Being concerned with what other people think has never occurred to Busch.

While a student at Northwestern University, Busch wrote and starred in Sister Act, a one-act comedy about a traveling freak show, in which he played one half of conjoined sisters. “Sister Act would be my first shot at writing, directing, and starring in a play—and at performing in drag,” Busch writes. “What a relief when I first saw myself in the mirror in full drag. I had small features, no discernible Adam’s apple, was only 5'7", and had been blessed with the same great legs as the women in my family. The point is that although I may not have been as stunning as Ann Sheridan (few are so fortunate), I could realistically look like the female character I’d written for myself. Never was there a thought that performing in drag could have any negative repercussions or even be considered an act of bravery. The question ‘What will people think?’ has put the brakes on so many creative aspirants and it’s something that’s simply never occurred to me.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.