Cedar Grove Cemetery: New Bern’s 200-year-old silent sanctuary a gateway to the city's past

This is the first in an ongoing series by reporter Todd Wetherington examining the beauty and cultural significance of our area's historic resting places through words and photos.

Growing up in New Bern during the 1980s, I always thought of Cedar Grove Cemetery as the center of my riverfront hometown. For reasons having little to do with geography, the roughly two and a half acre plot of land seemed to represent an unofficial demarcation point between New Bern’s fascinatingly derelict historic district and the newer city of Winn-Dixie grocery stores, mall arcades, and auto dealerships.

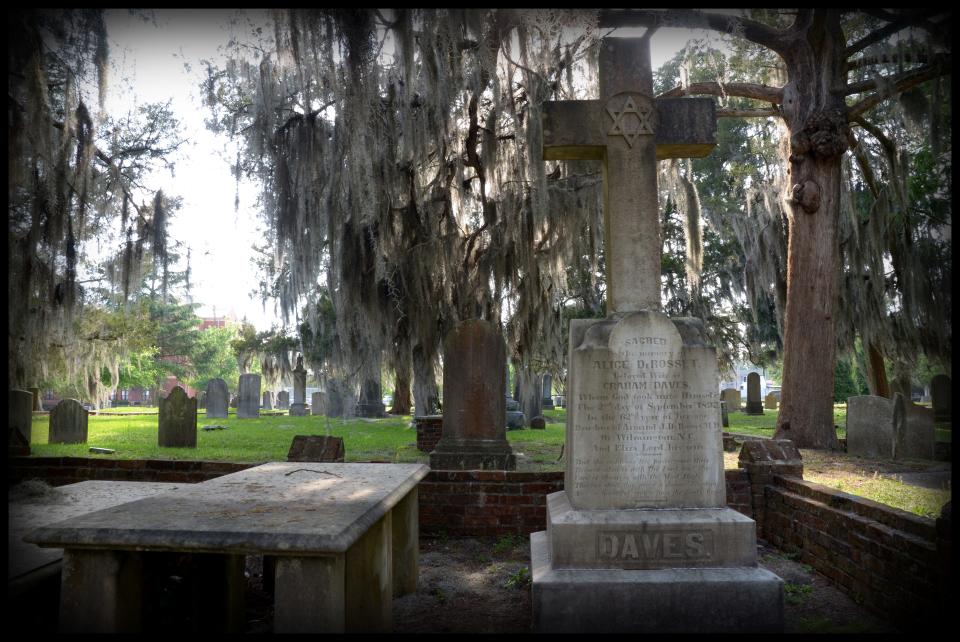

Behind its walls embedded with the shells of mollusks and other river invertebrates was a world older even than the city’s towering Masonic Temple and Harvey Mansion (though not quite as old as Tryon Palace). The Spanish moss-draped cedar trees that gave the cemetery its name and the seemingly ancient mausoleums stood in even starker contrast to a modern society that seemed increasingly infatuated with surface gleam and entertainment.

If I had known even a portion of Cedar Grove’s history back then, I would have had even more reason to be enchanted with the burying ground. Established in 1800, the cemetery was owned by Christ Episcopal Church until 1853 when it was transferred to the city of New Bern. According to local historians, it’s almost certain that the cemetery was established in response to the yellow fever epidemics of 1798-99. During that period “so many persons succumbed that at night trenches were dug in the Christ Episcopal church yard in a line near the adjoining property to the northwest… and the bodies were buried there indiscriminately,” reads one contemporaneous account.

After 1802 the cemetery became the major New Bern burial ground. The grave markers and cemetery records read like a “Who’s Who” of 19th and 20th century North Carolina’s most influential citizens: William Gaston, congressman, writer, state supreme court justice, and author of the North Carolina state song; William Williams, a portrait artist who painted from life the only Masonic portrait of George Washington; Moses Griffin, who established a free school and served the state throughout his life; John Stanly, lawyer, politician and public servant; and Mary Bayard Clarke, 19th century New Bern poet and writer.

With a good map a visitor might even locate the grave of perhaps New Bern’s most famous son, Caleb Bradham, who concocted his Pepsi-Cola formula in a local drugstore in 1893.

Cedar Grove Cemetery also bears witness to the region’s brief but lethal engagement in the Civil War. At the cemetery’s mid-point a bronze Confederate soldier rises 18 feet above its granite column, parade rifle at rest, a canon ball propped by his right foot and a sword slung at his side. The monument sits above a vault where approximately 67 Confederate soldiers are interred. A Latin inscription at the statue’s feet reads, “Dulce Et Decorum Est Pro Patria Mori,” (“It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country.”)

The cemetery has also borne witness to the slow and often painful civil rights struggles that have tested the country’s moral character since its very inception. In 1913 New Bern leaders made the shameful decision to remove the bodies of all Black residents buried at Cedar Grove and have them reinterred in Greenwood Cemetery. The act was necessary, they said, to create room for more whites.

Two memorial plaques honoring those dozen or more disinterred souls now greet visitors to both cemeteries, a reminder that, in our city’s recent past, even death offered no guarantee of equality for some citizens.

But for all its famous dead and memorials to history’s murderous advance, Cedar Grove Cemetery may be more well known among tourists for its looming black entrance arch. Built from the same shell stone as the cemetery’s wall, legend has it that if the arch “weeps” or “bleeds” its sticky, rust colored ooze on a pallbearer passing beneath, the unlucky individual will soon be the guest of honor at his or her own funeral procession.

Inscribed over the arch gates is a hymn composed by Francis Lister Hawks, grandson of Tryon Palace architect John Hawks:

“Still hallowed be this spot where lies

Each dear loved one in earth’s embrace

Our God their treasured dust doth prize

Man should protect their resting place.”

In 1972, Cedar Grove Cemetery was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Today, more than four decades after I first toured its grounds as a young boy, the cemetery is part of a downtown that has seen massive revitalization, as the city long ago embraced its heritage and earmarked funds to preserve its historical structures.

For me, the cemetery now feels more than ever like a sanctuary, from the renovated old homes and parks that draw tourists and from the big box stores that crowd New Bern’s business district. An island, for the living and the dead, carved from an older and stranger world. I drive past its walls sometimes just to remind myself that it’s still there, and that I am too.

Reporter Todd Wetherington can be reached by email at wwetherington@gannett.com. Please consider supporting local journalism by signing up for a digital subscription.

This article originally appeared on Sun Journal: Cedar Grove Cemetery: New Bern’s 200-year-old silent sanctuary