A Broadway Classic Has Learned Some Fresh Moves. We Talked to the Wizard Behind Them.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

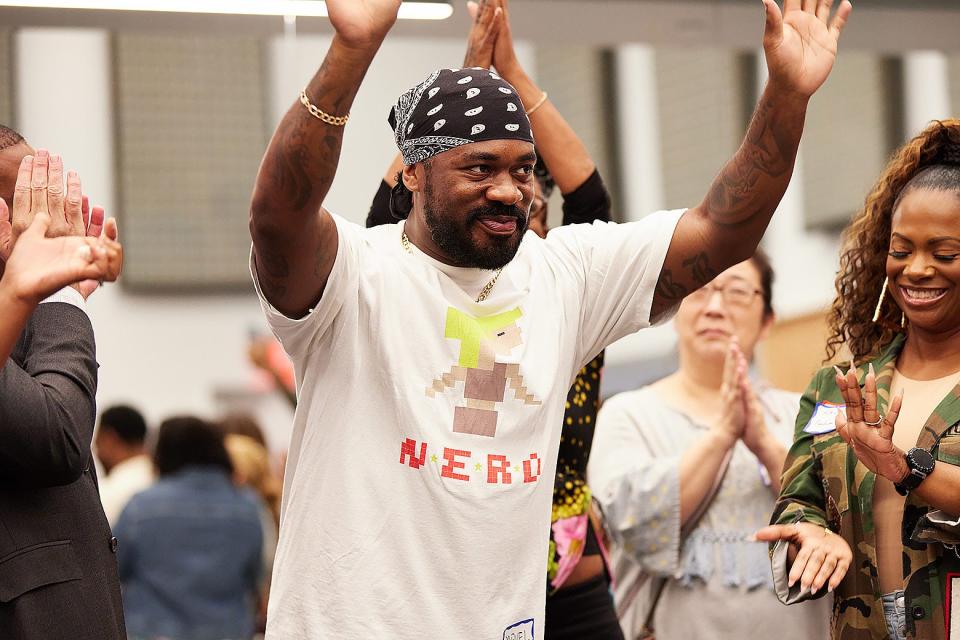

When it was announced that JaQuel Knight would choreograph the stage revival of The Wiz, a particular cross-section of the internet emerged to express a lot of excitement. These fans were not only those deeply familiar with the 1978 Sidney Lumet film or the 1974 Broadway production upon which the film was based, but also followers of today’s top-tier pop stars, female rappers, and R&B singers. That’s because Knight happens to be the mind behind some of our biggest stars’ most notable dance moments. Think Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion’s “WAP” music video, Beyoncé’s “Formation,” segments of Beyoncé’s acclaimed Coachella performance and subsequent concert film, Homecoming, and, most iconically, Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies” video—whose hand-twisting moves he conceived when he was just 18 years old.

Now, in an exciting turn of events, one of commercial music’s most sought-after choreographers is taking his talents to the theater. But the move doesn’t come without its challenges: Beyond embracing theatricality, for Knight there’s now the task of finding the right balance of paying homage versus putting his own spin on a classic.

Slate caught up with the artist to talk about his translation of The Wiz, how his commercial experience helped him craft his Broadway debut, and how Black joy is the through line in all of his work. This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Slate: What made you want to try this new genre?

JaQuel Knight: I’ve always had a love for theater. I feel like what we do in the commercial concert world, we’ve evolved that space from the inspirations that we’ve taken from the theatrical productions. I’m a storyteller too. I love that my movement tells a story and speaks to people—you can understand a person, where they’re from and where they’re at, from how they move. So that’s a huge part of it as well, it just makes everything meet there. And then it’s something new [for me].

I just want our people to know that we can do all things. You just don’t have to choreograph videos. Go and do it all. Be multi-hyphenated. You want to know all sides of you. And be great at it and let the people put some respect on your name.

You’re no stranger to crafting live performance—you co-choreographed Beyoncé’s famed Homecoming, for one. I was wondering, what are some of the differences between making something like Homecoming versus theater?

When you speak specifically to Homecoming, it was very much like choreographing for a Broadway show. We didn’t have as much dialogue. We had all those songs, but we wove that show together just how we did The Wiz. It was broken down into acts, and understanding what you’re trying to say and then executing it; again, inspired from the theatrical space. Generally, for concerts, it is just a music thing, but I just try to have art intersect. All parts of art. I think movement, dance, music, storytelling, understanding of what you’re doing and saying, should all marry at some point. You should have a voice, and people should come and be able to walk away with some sort of statement or understanding of where the artist is in life. I’m really big on who we are as people and where we are as artists: That should be placed into the art that we create.

One of the biggest differences, though, with something like a music video or Homecoming, is that there isn’t an original movie that people are going to compare the new version to.

The great thing about what Schele [Williams, the director] did was she really made us truly have a collaborative experience. So I’ll say the first two weeks, the creative team sat in the room and we went through every piece of material that has been released. We all knew [the original], and Schele had sent us all the previous script. So for us it was important to keep what was important, what we all felt like we held ownership to—and what Black Twitter had ownership to—but then also made sure we took risks like, “OK, they would appreciate this, they would love how this is moving.” Or, “Nope, we can’t do that. They’re going to read us.”

And then also just knowing that The Wiz comes with a certain level of joy, a certain level of Black excellence, a certain level of, “Wow, we can be something else besides depressed, sad slaves getting beat down.” It just showed another side of us as humans. We can be weird, we can be whimsical, we can dream, we can dance and sing and do harmonies and have great technique and be funky. For me, it was important to keep the essence of all of that. And then within keeping the essence, how do we make sure it’s current and speaks to the generation today?

I think a good thing that we’ve done as a team is we’ve created a piece that is timeless. You cannot put it in a place. Which is very funny, because the original Wiz is very set in the ’70s, but has become a timeless piece. Thankfully the music can never get old, so we were lucky with the property we had. But we took out all the buffoonery talk in the original piece, and then just made it a timeless classic that’s funny, with awesome music, and what I hope is kick-ass dance.

Thank you for taking out the creepy subway peddler with the puppets that grow, because that traumatized young me. I want to talk about modernization, because this version is certainly updated. What were some of your favorite parts of the original that you couldn’t wait to put your own spin on?

Obviously the introduction of Emerald City from the film. I think for me, that just spoke volumes of things that we can do. Even for me as a filmmaker and a choreographer, to look at all those people do that, it feels epic and iconic. That was probably my most exciting thing, taking that and twisting it, because I know people like myself growing up who didn’t see the original show and don’t know that Emerald City wasn’t a part of the original Broadway show. But I was like, people are going to come and they’re going to be like, “Where’s Emerald City? Where’s the dance?”

You’ve got to be seen green, baby!

What we did for this production is we took the genres of dance and style of music and switched it up each go-around. I think that gets the point across. And people really enjoy that part of the show. Within that, it speaks to this journey of Blackness where, in my mind, it’s the past, present, and future of how I see Black dance, Black music, and Black instrumentation. It was my most favorite part to choreograph.

Then, re-imagining the Poppies too. The Poppy Girls were probably my favorite thing in the film outside of Emerald City. So, I just was excited to give that a voice and put something sexy that had a little bit of oomph to it on the Broadway stage.

Louis Johnson’s choreography in the original movie is so singular and iconic. One of my absolute favorite parts is the middle of “Brand New Day”—

Oh my God, yes.

After Evilene is defeated, all of the workers under her spell shed their working garments and go into this joyful, jazzy contemporary dance while they’re basically naked. I was so excited to see your take on those standout dance moments from the movie, because they are so rooted in Afro-jazz, Broadway, contemporary, and tap. I think back in that day, until recently, the way that people of the Black diaspora would most commonly relate to African dance was through Afro-jazz and the Alvin Ailey style of Afro-contemporary. Nowadays, Afrobeats and amapiano are how we most connect to African music and the idea of African movement. I thought the inclusion of modern Afrobeats music and dance in the revival was poignant, because a lot of the intention of The Wiz seems to be an exploration of how Black people everywhere might relate to art from the continent, and you still have that—it’s just not the same Alvin Ailey–like connection that it was before, but a more accurate representation of that connection today.

There used to be a full amapiano section in the Emerald City world, and then we took that music and split it up. When they first open the gates of Emerald City you can hear it; that piece of “Brand New Day” was part of our Afrobeat inclusion, which represents the future. This is how the future of us lives, and it’s just that: still having that point of connection and relation to the motherland, and understanding that this is where we come from, but this is also where we’re going. It’s that trippy circle that we’re going into, understanding where you come from, but also knowing that we’re going back to the same place. So it’s really a really good tie there that you nailed.

There were some other modernizations, like Phillip Johnson Richardson’s Tin Man had a whole hip-hop dance breakdown and Wayne Brady’s The Wiz also did an ’80s/’90s dance break as well. How much of those decisions are you dictating what you want from the get-go and how much of them are you working with the talent’s strengths?

It was a bit of both. I knew we wanted the Tin Man to feel cool and super grounded and bring another sense of ability. It’s interesting that the original Tin Man only tap-danced, but tap generally isn’t a dance style that you feel requires your entire body. So that reinvention of the Tin Man was intentional; we thought he should really come into a place of full movement and excitement. But then it also made sense with Phil, so that married perfectly. But then there are [legends] like Wayne, and it’s like, “We’re going to put a dance break here, Wayne. What do you want to do?” “Oh, I would love to do a ’90s dance break. Maybe we should do something like this.”

The Adidas tracksuit! He’s locking (and maybe doing a little popping) in the Adidas tracksuit. It’s so perfect.

Once you find out he’s this scam artist or con artist, [the number] just totally makes sense to his storytelling.

Obviously, Michael Jackson is a huge, huge, huge figure. When it comes to crafting your version of a number like “You Can’t Win,” performed this time by Avery Wilson, how much of that was inspiration from the original and from Michael? I feel like I maybe even caught an MJ reference in there.

“You Can’t Win” has gone through a few [iterations]. I think in my original workshop I choreographed a section of it where I actually wanted to include tap, so we had a bit of footwork. And I wanted “You Can’t Win” to feel like a classic. For me, that’s the classic Wiz number in the show. It’s a little more jazzy, there’s a lot of great lines in it. We crafted a really great number that we toured. And then halfway through the tour, I went back to the Michael performance and I was like, “OK, maybe I can use a bit more of this from the film.” We do a cool thing in the story where the crows aren’t—

They’re not mean! I noticed that change from the film.

Scarecrow just takes it the wrong way and doesn’t understand [his predicament] until Dorothy tells him to change his perspective. So, [with the crows being nice] I felt like they were a great support, like the Supremes, or any of those great groups with the lead and three behind them. That was a huge part of it. And then also understanding there was a freedom in the Michael numbers. Michael’s a spirit that you can’t compare to. He’s just otherworldly human—not even human. A robot, super-figure. You just have to keep that out your way because you’ll kill yourself trying to compete. Instead, just create from the essence of, or spirit of, the original. I think we have that when you see it.