Brett Morgen Had a Heart Attack Making ‘Moonage Daydream’ — and Credits David Bowie for His Recovery

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Editor’s note: This interview was originally published at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival. Neon releases the film in theaters on Friday, September 16.

Documentarian Brett Morgen has tangled with rock legends before, with “Cobain: Montage of Heck” and Rolling Stones doc “Crossfire Hurricane,” but when he landed the plum assignment of directing the first officially sanctioned David Bowie documentary feature, he had no idea what he was in for. Finishing the movie took five years of absorbing Bowie’s massive archive by himself, tracking down hi-res footage and music stems suitable for IMAX and Dolby Atmos showings, and editing all alone during a pandemic. No wonder Morgen suffered a heart attack and wound up in a coma.

More from IndieWire

Armie Hammer Docuseries Is for the Person Who Knows Nothing About Armie

'Fragments of Paradise' Review: Jonas Mekas Doc Is a Message from Beyond the Grave

He insists that it was all for the best and turned him from a child-man into an adult — and that Bowie’s philosophical musings on art and life enabled him to complete the movie. To chart Bowie’s creative, musical, and spiritual journey, Morgen dug into a kaleidoscope of never-before-seen 16 and 35mm performance footage and movies, with narration from the musician’s interviews. Clocking 140 minutes, “Moonage Daydream” (referring to Bowie’s song from the 1972 album “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars”), finally debuted as a Cannes Midnight selection at the Grand Theatre Lumière, complete with Morgen’s spontaneous jubilant dance up the red carpet and a rousing after-screening standing ovation.

It was 20 years since he had played his Robert Evans documentary “The Kid Stays in the Picture” in the tiny Buñuel theatre, and Morgen was enjoying the moment. “When I got to the red carpet, I don’t have a team, I’m by myself, I’m walking in,” he told me the day after the Cannes premiere. “I thought to myself, ‘I’m going to take my time; I’m just going to soak this in.’ And I got in front of the first group of photographers and all of a sudden [he hums the opening chords of ‘Let’s Dance’] and I can’t not dance. The press were goading me on and I can see that they were sort of having a good time. And it was pure joy.”

Neon will likely next book the movie at the IMAX theatre at the Toronto International Film Festival before hitting screens on September 16. The movie took so long to get made that its release plans were forged in the pre-streaming era. Morgen insists that IMAX is the best way to experience this immersive and dense collage of Bowie performances across many disciplines, from music and film to dance, painting, sculpture, travelogue, writing, interviews, and theatre. In Spring 2023, six months after its release, the film will be available on HBO Max.

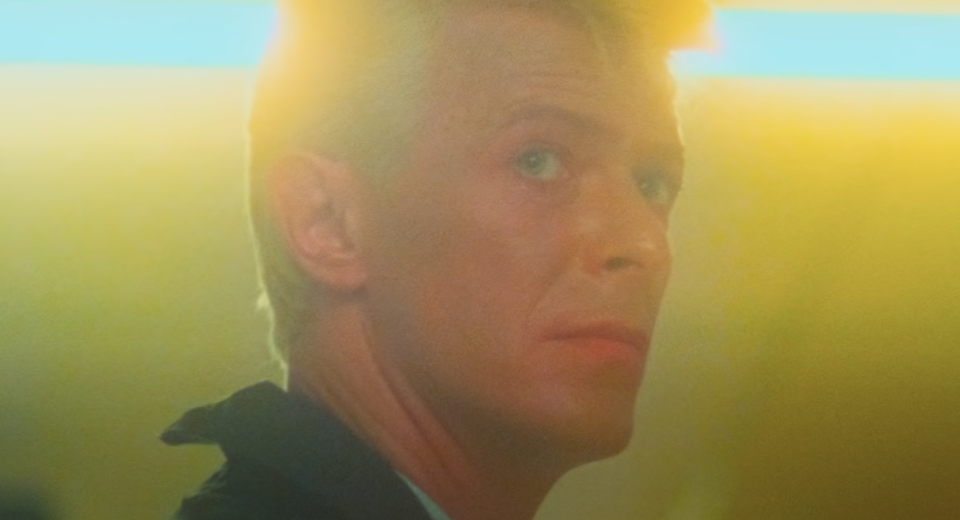

screenshot/Neon

Morgen first met with Bowie in 2007 to pitch a hybrid nonfiction project that would have involved Bowie performing for about 50 days, which the singer was not healthy enough to take on at the time. Three weeks after the singer’s death in 2016, Morgen reached out to Bill Zysblat, the artist’s manager-turned-executor. Zysblat remembered that Bowie had liked Morgen, and responded well to his new pitch for a non-biographical approach to a wall-to-wall music movie with no talking heads.

The estate gave Morgen full access to Bowie’s personal archives, including all of his master recordings. He uploaded all the digital material onto his computer and watched every snippet. It took two years. “Moonage Daydream” features 48 of Bowie’s musical tracks, mixed by Oscar-winner Paul Massey (“Bohemian Rhapsody”) from their original stems in Dolby Atmos. All of the film performances appear for the first time.

IndieWire: What was the nugget of your Bowie pitch?

Brett Morgen: In 2015 I was at a screening of “Montage of Heck” at the Paramount at South by Southwest with David Fricke from Rolling Stone. I mixed the music scenes really loud. And Fricke said, “I’ve been at 12 Nirvana shows and that’s as close as anyone’s ever gonna get to seeing Nirvana.” And in that moment, something clicked. And I thought to myself: “Movie theaters have the greatest sound systems for listening to music. And why do we waste that space on biographies you can look up on Wikipedia? Let’s create a new form of cinema that’s just experiential, that doesn’t need a narrative or biography, just a format to capture the essence of an artist.”

And then David passed in 2016. And I called Bill Zysblat. And he said, “Most people don’t know this. But David saved everything. He’s been collecting everything from the very beginning, but particularly in the last 20 years, he was buying stuff at auctions and really building out the archives.” And he at one point was talking to Bill and said, “What are we going to do with all this stuff? I don’t want to do a trad documentary.” And so my pitch to Bill was, I want to make a film that’s just an immersion into his creativity. And Bill said, “This is the perfect opportunity. This is a perfect synergy.”

NEON

Did you see the Bowie touring museum exhibit?

I was working on the film when I saw [the exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum] and I felt like I walked into my movie. I called the estate afterwards. I said, “Okay, it’s been very difficult for me to explain what my film is. It’s the experience of walking your exhibit.” Because “Moonage Daydream” is not a film about David Jones. And it’s not a film about David Bowie. It’s a film about “Bowie.” And the visual language of the film was that everything is performance. So whether he’s an actor in “The Man who Fell to Earth,” or he’s on stage singing, or doing an interview, it’s all performance. So I was going to treat all images of David equally. I also made a decision before I started making the film, that one of the one of the great joys of Bowie is how he introduced me to Bertolt Brecht and William Burroughs and you hear a song and you hear him talk about a reference and you go look it up. And now I know about Kandinsky and German Expressionism and I wanted that to be part of the fabric of the film. So I created a database in my Avid of all of his inspirations through choreography, philosophy, film clips from films that he admired, and I would just grab those images at random when I needed to evoke something.

What is that repeated black-and-white footage of a moonscape?

That was a film called “Universe” from 1960, a CBC documentary that was Kubrick’s biggest influence on “2001: A Space Odyssey,” which was a huge influence on Bowie. He had the “Universe” film print in his possession in the ’70s.

Were you overwhelmed by the archive?

When I’m going through materials, I’m usually just trying to absorb. You only get one chance to see something for the first time. So I’m trying not to write the film then, I’m just trying to immerse myself until I get to the end. And that’s when I start writing. So for two years it was like going to watch television. Watch David Bowie every day. I was by myself. Everything was transferred over to my office, digital. We scanned every document. I’d asked our staff to organize things chronologically, but there wasn’t a table of contents. I would know what year I was going to go into that day, but suddenly the “Diamond Dogs” tour comes on and I’m like, “Oh my God, I didn’t know there was footage of the ‘Diamond Dogs’ tour.” And now I’m watching the entire Philly “Diamond Dog” show, and you want to turn it and put it on YouTube. You want to share it with the world. I watched every frame. I didn’t want to miss anything.

Why did you let that incredible performance of “Heroes” play out?

Because it was emotional. That was never before seen. It’s 1978, from Earl’s Court. Bowie fanatics know that that show was filmed but had never seen the light of day. So when I walked into the vault, the first time I saw stacks of 35 mm cans that said “stage,” “What’s that?” And they’re like, “Oh, David lost interest.” And it’s been sitting here for 40 fucking years. And the film used to end with a 12-minute performance from that show of “Station to Station.” Sean Penn was the first person to see the film. One note was to cut that out, that I had said everything I needed to say by then. So we went back. Not just because he said it, it actually resonated. He’s the only person who had any major editorial input.

Anthony Behar/NatGeo/PictureGroup

Where did the footage of him wandering up and down escalators in Asia come from?

In 1983 Bowie was on the “Serious Moonlight” tour. They had been on the road for nine months, he didn’t have a home to go back to. So when they reach Auckland, he said, “Bill, can we go tour Southeast Asia? And let’s use the money from the tour to do a little travelogue piece.” So he made this film “Ricochet.” It’s so obscure that it was not on YouTube when I started the film. I could only find a VHS tape. When I saw it: “This is the holy grail. This is what I’m missing. This is the visual metaphor that I need to tell my story.” And I call Bill and say, “I need to find the masters for ‘Ricochet.'” Nobody knew where the masters were; there was only a three-quarter-inch master and it was no way going to work in IMAX. And Jessica Berman Bogdan my archivist who I’ve been working with for 25 years found the 16 millimeter negative mislabeled in a vault in London. And when we saw the 4K transfer of it: “Oh my god.”

So regarding the length of the movie, it’s always a question, when are you done?

When I put together my playlist for the film, there was going to be an intermission. It’s Bowie. It’s got to be three, three and a half hours. Originally I wanted to get deep into the ’90s, into his work in the early 2000s, which I came to appreciate. But I realized that once he arrived at Iman he plateaued. And his approach to work changed, it wasn’t as intensive as it was prior to that. He opened up a part of himself that wasn’t there. So I just felt at that point it was a series of great albums. And the story hadn’t landed. And so I stopped there.

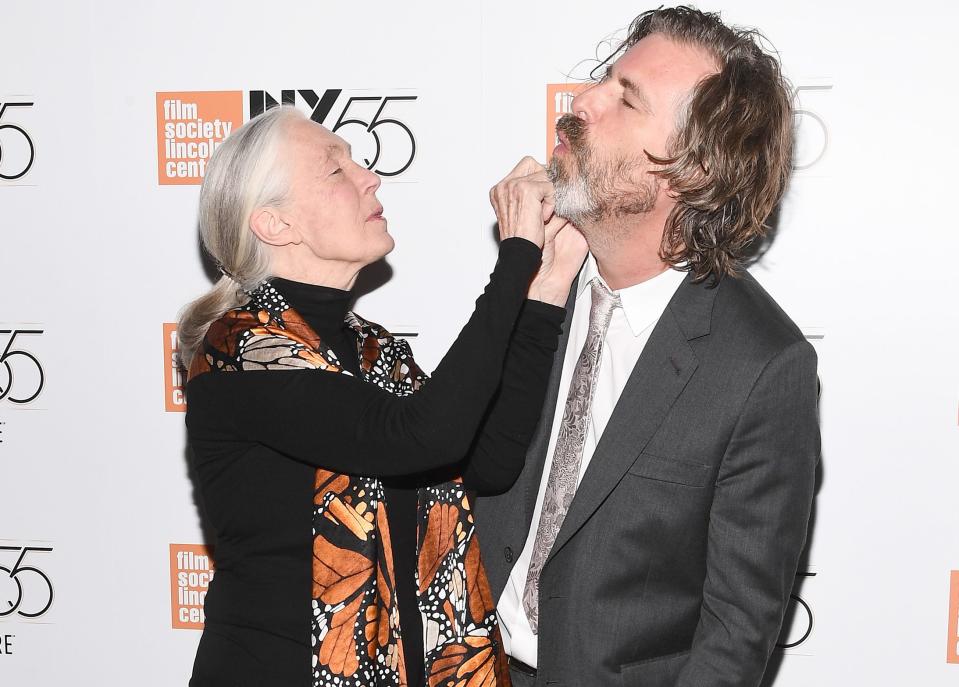

Anne Thompson

Was the Bowie narration fairly chronological, showing his evolution?

He talks about certain things at certain times, he comes back to chaos and transience, from 1971 to his last interviews, it’s the most consistent theme in his interviews and the area that he’s most passionate discussing. But I assembled the film by creating these blocks, themes: spirituality, mortality, aging, creativity, and pulled all my favorite bites and put them in.

Where do the Bowie interviews come from?

All over the place. My favorite one was the outtakes for the Michael Apted 1997 film “Inspirations.” Michael did portraits of eight different artists, and because the interview was about David as an artist, about his creative life, he was speaking artist to artist. I pulled from that more than from anywhere else.

Editing must have been a bear.

It was like a house of cards, I would have 29 days of working 16-18 hours a day and get nowhere, nothing, not one frame advanced, torturous, because I was my own editor, and my own producer. Once we got the material from the estate, I had budgeted for four months of screening. And it was two years of screening, and I couldn’t risk paying an editor $6,000 a week for two years, to then start cutting the film and find out that they’re not the right editor for the film. So the only way this would work is if I screen everything; our investors weren’t going to give us any more money.

It’s unusual for it to just be you.

Well, I had a personal assistant who’d never worked in film before. And he was, besides me, the only person who was involved in line producing, post supervising. He got to learn everything on the film. It was a bit batshit crazy. And then there was a pandemic. And I have a heart condition.

screenshot/Neon

You had a heart attack. It must have been horrible for you and your family. I’m sorry.

Thank you, but I’m not. It was horrible. But it got me to such a better place in my life. I could not have made this film, if I didn’t have that experience. I was not ready to make a David Bowie film in 2007. I was a man child until my heart attack and probably for another year after that. My life, and my sense of self and my sense of self worth, have always been defined by my work. And I’ve always prided myself that I’ll work longer in the night than anyone else. I’m first in and last out. So, when I had the heart attack, it wasn’t an accident. It was a sign. Why does someone have a heart attack at 47? You can click off every reason: I had them all. I was in a coma on my daughter’s birthday, which was exactly one year from the day David died. And when I came out of that, I started a process. I could have died in that moment. What was the message to my children? Work hard and you’ll end up like that. And at the same time, I’m listening to David and I’m immersing myself in David. And I realized that through his words, I could present my children with a roadmap for how to live a fulfilling and satisfying life in the 21st century. And David Bowie, the man who I don’t really know, but the person that was guiding me, taught me how to live. It was very profound. He changed everything for me. I mean, I’m still a little hyper obviously, as you can see last night, but in the moment.

Are you healthier now?

Well, this film was difficult on my health. Yeah, it really, really was. I got two CT scans while I was making it. After the heart attack I was having trouble with my memory. And when I went to edit, it was two years after I had first seen that footage. And I started to lose my mind, because I started to forget that I’d seen stuff. I would see stuff and not recall that I’d already seen it. But I didn’t have an editor, I didn’t have someone else tracking it. So if it went out of my head, it was gone.

Did you ever think about bringing someone in to help?

The pandemic meant I couldn’t be in the room with someone, I couldn’t be in a building with someone. We had no more money to hire anyone at that point. So I had to figure my way out of this mess. The most frightening part of it was we had blown through all of our money before I started editing. And when I went to go write the film, I didn’t know how to write it. I don’t know how to write an experience: “I’m a total fraud. I sold my investors this experiential cinema. I don’t know what the fuck I meant, it was a pitch! If they were smart executives, tell me what happens at minute 17.” But they bought it all, like it’s going to be wild and crazy. What was particularly difficult too, is it’s Bowie.

He’s beloved. The sound mix is elaborate and layered. Was it all coming through at the Lumiere?

The film in IMAX is night and day to what you experienced last night. It is a totally different experience. It was designed for IMAX, not for 7:1 [surround sound]. It’s a dangerous mix. Depending on the theater, it can go off the tracks. Last night it went off the tracks. That theater is meant for dramas. It’s meant for dialogue-driven films. It is not meant for our mix. Last night was a little bit of a disappointment.

So the movie is Dolby Atmos and the theater is not?

The theater is not Atmos. We played in 7:1 last night. If you saw it in 7:1 at the Blakely at Fox, it’s a small room, so you can hear things as they’re wrapping around you. Last night I couldn’t hear things. See the IMAX version. It was Paul Massey, that music mix. He’s a legend. So my whole reason for making the film was to take stereo music and spread it around the room.

Part of that was when I saw Cirque du Soleil’s “The Beatles LOVE” I felt like I was really discovering the Beatles. It was around 2006. I used to go see Pink Floyd’s Laserium at the Griffith Observatory like every fucking Friday and Saturday in 11th and 12th grade. So I really wanted this kind of wraparound immersive design. And the reason to make the film was to take stems and spread them out and allow you to feel like you were inside of it. It’s a different way to experience music.

Whereas where I was sitting last night, I couldn’t even hear the sides of the room. So the idea was to allow the audience to have an experience not that dissimilar from headphones. Paul kept me in check because, as he’d constantly say to me, not all theaters are the same, except for IMAX.

Should “Moonage Daydream” be seen in IMAX?

We were very aggressive on the IMAX, because we know that every IMAX theater plays it at the same sound, the same speakers, in the same distance. And you can really put your foot down versus the 5.1, which is for the movie theaters that don’t care about sound. That mix is restrained, it’s like watching on television. So we created separate sound.

Do you read reviews? Cannes critics have described your film as “impressionistic,” “a collage,” and “busy.”

Some reviewer said, “It seemed a little indulgent.” I was like, “a little? I’ve never been against art that’s indulgent. I actually prefer art that goes all in.”

Best of IndieWire

New Movies: Release Calendar for September 2, Plus Where to Watch the Latest Films

'White Noise': All the Details on Noah Baumbach's Film Starring Adam Driver and Greta Gerwig

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.