Breaking Baz at TIFF: ’American Fiction’s Debut Filmmaker Cord Jefferson Donated A Kidney To His Father – And Made One Of The Year’s Best Movies

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

EXCLUSIVE: Filmmaker Cord Jefferson has, in recent years, made two life-changing decisions.

In 2008, he donated a kidney to his father.

More from Deadline

“That was easy,” he said.

“That was one of the easiest decisions I ever made. I mean, he gave me life. I feel like the kidney’s half his,” the 41-year-old declared.

A few years later, Jefferson read novelist Percival Everett’s book Erasure.

Then he adapted it for the big screen and called it American Fiction. The project became his feature film directorial debut.

The searingly provocative movie had its world premiere at the Toronto Film Festival and has emerged as one of the best films of the year, joining the handful of movies that have so far galvanized the fall festivals at Venice, Telluride and Toronto.

Orion Pictures releases American Fiction in select theaters November 3, expanding it November 17.

To my shame, American Fiction had not registered in my mind when I gave this year’s TIFF titles a cursory glance when the films were announced.

RELATED: TIFF 2023 Has 50 Acquirable Films & Few Stars To Promote Them; Will Hungry Distributors Pounce?

Jefferson’s reps at Rogers & Cowan/PMK sent me a note last week pitching Jefferson as a possible candidate for an interview.

They’re good people, but I was wary.

Jefferson is Black, and I bristle, ever so slightly — but not in every instance — whenever a new Black artist comes along and people want me to meet them.

Why have they come to me?

I’m damning myself here because it’s pertinent to the topic that underpins American Fiction.

The movie subverts the white lens and satirizes how my Caucasian brothers and sisters react to Black culture; in this case publishing, and the motion picture industry, too.

The stereotypical cultural tropes we know so well are mercilessly ridiculed.

And, in part, both Everett and Jefferson also observe the Black perspective; as in how do Blacks perceive this stuff? By the way, we’re not all of the same opinion.

Our angry hero in American Fiction, played with electrifying authority by Jeffrey Wright, is one Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, a published author and a professor of English literature.

Monk’s peeved because his latest offering hasn’t caught fire with publishers, while on the other hand a tome on urban misery called We’s Lives in Da Ghetto, by a Black writer named Sinatra Golden (played by Issa Rae) hits the bestseller lists, leaving Monk seething.

Rae’s Golden reads out an excerpt of the book on a festival panel, providing a hilariously scathing moment of mockery.

The thought keeps flashing in my head that I nearly didn’t see American Fiction at all.

Funny how a casual remark made to me by Jerry Rojas, Shelter PR’s awards and events supremo, reminded me of the message from Rogers & Cowan/PMK. As soon as Rojas uttered the title I had an epiphany that I should see American Fiction — like that night, like in about half an hour. Rojas saw my eyes flash and found me a ticket.

I’m detailing all this blather because I want to make clear that seeing American Fiction was a spur-of-the-moment thing.

Running parallel with Monk’s literary determinations are the irascible writer’s issues with his family: namely his mother, played by Leslie Uggams; his sister Lisa Ellison, played by Tracee Ellis Ross; and other sibling Clifford Ellison played by Sterling K .Brown. Not for me to detail what occurs, but of course, stuff happens to them.

Monk decides to pen, using a pseudonym, his own cop-out urban book, which he entitles My Pafology and then, in a bid to derail the deal, he demands it now be called FUCK. The white publishers are on board because they think it’s so darn awesome. White folk will gobble it up. And they do.

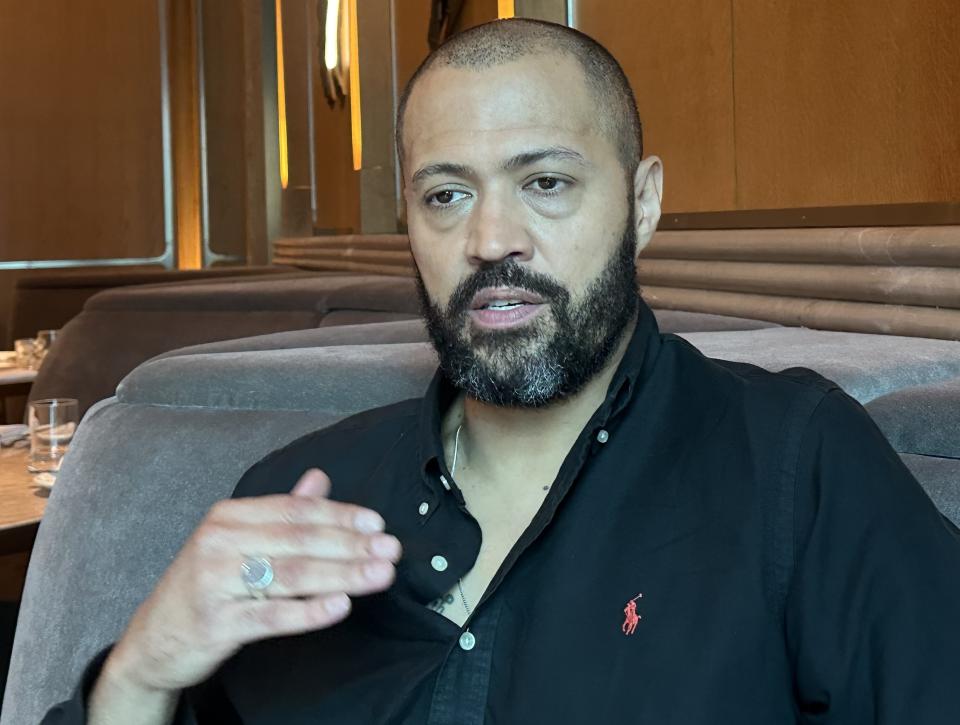

”I wanted it to be satire without becoming farce. That was important to me,” Jefferson explained when we met for tea in the 31st-floor restaurant at the St. Regis in downtown Toronto.

Jefferson continued, ”I think that some satire becomes farcical, and I think that’s totally fine. I think there’s some great farcical films, but I didn’t want to do that with this. I wanted it to feel satirical but also grounded. I think the blending of the family stuff in there grounds it. It grounds the film before it becomes just pure satirical farce.”

Jefferson has worked as a writer, executive story editor, consultant, co-producer or supervising producer on The Nightly Show with Larry Wilmore, Succession, Watchmen, The Good Place, Master of None and Station Eleven.

He won a Primetime Emmy for co-writing with Damon Lindelof the Watchmen episode “This Extraordinary Being.”

In December 2020, Jefferson read Erasure.

He explained how he’d been reading a review of Charles Yu’s National Book Award bestseller Interior Chinatown “and it said that there that it was a satire reminiscent of Percival Everett’s Erasure. I’d never heard of Erasure, so I went and looked it up and bought it and just devoured it in a week over Christmas break, and knew instantly as soon as … I started reading Monk’s lines in Jeffrey Wright’s voice. That’s how immediately I knew I wanted to adapt this, and I wanted to reach out to Jeffrey Wright. I Initially thought that I just wanted to write the script, but by the time that I got to the end of the book, I realized that I was feeling such a connection. I felt it so deeply in my bones that I wanted to try to make this my first shot at directing as well.”

What was it he felt deeply in his bones?

”Well, firstly, a large part of it, it’s about family dynamics and siblings and difficult fathers and an ailing mother. And I’ve had all those. I have two siblings like the character of Monk. Like the character of Monk, I once moved home to take care of my ailing mother who was dying of cancer,” he revealed.

“So it’s all of these complicated family dynamics. Then on top of that, there was the whole satire about being a Black writer and a Black creative, what it means, what the expectations are when the cultural community comes looking for Black art and what Black art looks like to people. These were conversations that I’ve been having with my friends since I started working in creative industries. These are things that aren’t just limited to the Black experience. I’ve got a queer bunch of friends who feel the same way. I’ve got a bunch of Asian friends who feel the same way. I’ve got a bunch of Latino friends who feel the same way. So it was just this broader conversation that I’d been having with a lot of people.”

American Fiction has touched a chord. “I think that the number of Black people who watch the film and say to me that it triggers so many memories of experiences they’ve had in their career. I have Latino friends who say, ‘Every story they want is about the drug cartels and the rough immigrant experience where we’re racing to get across the border from this terrible place that we live in. That is not the case at all.’

“I think that it’s certainly the case for some people. It’s certainly some people’s lived experience, and we don’t want to detract from that. But the question is, why isn’t there room for more stories? It’s not that those stories shouldn’t exist. They should because they are truthful, and they’re people’s lived experience. I love a lot of those movies, and I think that a lot of them are very important and good. I just think that we make those and omit everything else. So it’s not that those shouldn’t exist. It’s that, why are these the only things that exist?”

At a recent post-screening Q&A, Jefferson skewered the entertainment industry for its often shallow focus.

He expanded on that thought, decrying the situation for ”its poverty of imagination about the depth and breadth of other people’s experience. It’s certainly like a Black American life is different in many ways from a white American life, but it’s also incredibly similar, and I think that there’s an inability to believe that, that truth.”

Everett “very generously gave me the rights [to his Erasure novel] for free and said, ‘Feel free to adapt it and write a script. Then if anything comes of the script, then we can talk about how much I’ll charge you after that.’ ”

The script was written over the course of three months.

A lot of producers wanted to meet on it, but Jefferson decided to link arms with Rian Johnson and Ram Bergman’s T-Street “because they greenlit it, and they had money from MRC. They said, ‘We’re going to make this movie.’ So they were the only ones that we had a meeting with who said that. Then from there, we started shopping it around distributors once we had Jeffrey attached and once we had the script and once we had producers. That was very fascinating because we met with so many people. We met with so many distributors, so many streamers,” Jefferson added.

“The number of people who said, ‘I really wish that I work in a place that would allow me to make this film. I really wish that I worked somewhere where I could make this movie. I really wish that I could make this movie, but I just can’t,’ ” he recalled of those conversations.

Which streamers are we talking about here, I prodded.

”I don’t want to name names. But It was also a bunch of distribution companies. So it’s not just the streamers. Some people said, ‘I wish that I worked at a place that could make this. I love the script. I love Jeffrey Wright. But I don’t have the juice to make this.’ I think that, for me, what that spoke to was, it’s like, ‘You do work at a place that can make this movie. This isn’t a $250 million movie. It’s not going to bankrupt you. Even if I make it and it’s a disaster, it won’t affect your bottom line in any real way, probably.’ I just realized that there wasn’t a political will to make it. There was a fear that, like, ‘Trying to get this made is just going to be impossible here, and I am not going to go through with it, because for whatever reason, it just doesn’t seem feasible.’ “

He shook his head and said, “What frustrates me about Hollywood sometimes is this idea that there are so many smart and talented people in the industry, but sometimes there is just an apprehension to do anything that isn’t a guaranteed success. That, to me, really hurts the work that comes out of the industry and really, I think, hurts culture in general. I think that it’s gotten worse as things have gone on. I just think that now there is this tech ethos that has started to influence entertainment. It’s like, ‘Well, if the algorithm doesn’t tell us that this is going to be successful, then we’re not going to risk our necks in making it. You need to satisfy the algorithm and satisfy what our data shows us to be successful.’ To me, that is a very, very bland way to make art.”

We agreed that Steve McQueen’s Oscar-winning 12 Years a Slave is not a part of the movie misery porn bandwagon in the way that I thought Steven Spielberg’s adaptation Alice Walker’s The Color Purple was. It was so clean. Don’t get me started on Antoine’s Fuqua’s Emancipation.

“Yeah, Steve McQueen’s incredible. I love him. I don’t think that his movie shouldn’t exist. I don’t think that his movie is bad. I think it’s actually very good,” Jefferson said. “I’m happy, especially in an America where we have so many people actively trying to erase these parts of history and not teach them in our public schools. So I think that these kinds of things are very valuable. I just want people to understand that there’s also another side. I don’t want to play respectability politics. I don’t want to get into the Bill Cosby thing where it’s like you need to pull up your pants and pull yourself up by your bootstraps, and you’re the reason for your own demise. I don’t believe that either.

“All I want out of this, if this film is to effect any change, it isn’t saying there’s a right way to be Black or there’s a wrong way to be Black because there isn’t. I just want this film to let people know that there are other stories out there. You are diminishing the Black experience by pretending that it’s just all misery and that the only people worth discussing are slaves or drug addicts or gang members and that our lives are limited to that. I don’t think that there is an acceptable way to be Black. I think that there’s just, you’re Black, and you need to figure out how to be Black in a country that has a problem with that a lot of the time.”

Is there an acceptable way of how to be Black in front of white people?

“No, no, absolutely not,” he responded.

“I don’t ever want to make anything that says there’s an acceptable way to be yourself. I think that’s up to every person to decide for themselves.”

He cited the plight of a Black friend to illustrate one of the problems with the white gaze in culture.

His friend loved American Fiction but admitted that he found it a little painful. Because the friend recognized an instance in the movie that in a way mirrored something he’d experienced.

Jefferson said the friend told him that one of the first screenplays that he sold ”played into all of those stereotypes because I knew that that’s what the market wanted.” He said, “I sort of diminished a part of myself to do that, but I also wanted to make a career in this industry.”

Jefferson said that hearing his friend ”say that, I just think that that is the reality for a lot of artists of color, for a lot of queer artists. A lot of artists from these marginalized groups, I think, realize that, ‘Okay, this is difficult. It’s a difficult industry in which to make a living. It’s a difficult road to hoe when you’re trying to start out.’ So because of the white gaze and because so many of the people who are making these greenlighting decisions are white people, I think that there is a limited perspective sometimes on what people think that they can make and what they’re allowed to make. Because the reality is that sometimes it’s very difficult to get things made, and sometimes the path of least resistance is just giving the people what they want.”

My own interactions with regards to race amuse rather than anger me. And I can laugh at the absurdity of the instances of racism that occur daily. I’m of an age where I have to laugh at it. However, I’m often outraged on behalf of others, but I can look after myself very well.

Jefferson nodded, then remarked that “these are, of course, serious issues. Of course, racism is an awful thing, and it sometimes has fatal consequences. But if we can’t find an ability to laugh in the absurdity of all that, then we’ve really lost.”

Wright is one of the key reasons American Fiction takes hold of you.

For me, Wright broke through in the original 1993 productions of Tony Kushner’s landmark Angels in America, Millennium Approaches and Perestroika, that George C. Wolfe (himself responsible for the powerful Rustin movie here in Toronto) directed at the Public Theater, and later on Broadway; and when he played the titular role in Julian Schnabel’s movie Basquiat in 1996.

“He’s one of our greatest living actors,” Jefferson proclaimed.

“And I think that giving him a lead role was a dream of mine just because I’ve been such a fan of his for so long.”

The film’s cast also includes: Erika Alexander, John Ortiz,Myra Lucretia Taylor,John Ales,Stephen Burrell,Keith David,Adam Brody,Miriam Shor and Michael Cyril Creighton.

Jefferson’s own tears bind the fabric of American Fiction.

“My mother died of cancer, it’ll be eight years in January,” he said, speaking movingly.

“For the last month of her life, I came home to stay with her at the hospice as much as I could.”

This was in Tucson, AZ, where Jefferson was raised. He’s the youngest of three brothers, but his mother’s only son. His older siblings are half-brothers from his father’s first marriage.

He’s quick to praise an older sibling who lives there. ”He was very much the person who took her to her chemotherapy appointments, who picked her up from radiation, who ran errands for her and got some stuff when she wasn’t able to do things for herself. He was very much shouldering that responsibility in a way that made me feel really guilty because I was off in New York City working on a TV show. I would call home and talk and interact, but I wasn’t there. I wasn’t actually there. So I felt a lot of residual guilt about that, and I felt awful.

“So, yeah, that kind of sibling dynamic and the anger that you have at your siblings but also the easy relationships, a lot of the family stuff [in American Fiction] is taken directly from my personal experience,” he said.

During his Emmy acceptance speech, Jefferson spoke candidly about mental health issues and therapy.

The root of his anxieties, he told me, had to do with the trauma, and inherent racism, of not meeting his maternal grandparents, who were white.

“My mother was disowned by her family for marrying my father,” he told me. “I would send them letters. I would send letters to my grandmother and grandfather and they would return them unopened. My mother didn’t speak to her father until he was on his death bed.”

Jefferson never did meet them.

But his mother and her sister were very close. “My aunt kind of took my mother’s side, and they were very close until my mother’s death. Then her brother took the father’s side and was out of our lives. I didn’t really meet him until about three years before my mother passed. He then came to the funeral after my mother died, and he said … I’ll never forget it. It was so haunting. He said, ‘I will never forgive myself for abandoning my sister.’ He said, ‘I cannot believe that I did that, and I will never be able to forgive myself.’

“There’s a lot of family trauma,” he cautioned.

“But you can’t sit around thinking about all these horrific things that happen, because if you do, you’ll never accomplish anything.”

His parents met at William & Mary University. Jefferson told me his father was the second Black graduate of William & Mary Law School.

Jefferson also attended William & Mary but majored in sociology, not law.

“I think that for me, it was like, that’s not for me,” he argued.

However, he wished “that I would’ve trusted myself to be an artist earlier, and I think that I didn’t, because I felt like I didn’t have the thing. I didn’t have what it takes, and I didn’t have the pedigree, and I didn’t have the lived experience of that. My parents weren’t famous. My parents didn’t have a ton of money. I just think that there was all these things that I used to comfort myself when I was feeling afraid, and I wish that I would’ve conquered those fears a little bit earlier.”

I wondered if he’s still afraid?

“Yeah, yeah, I am,” he said. “But I think that I’ve learned to conquer that fear. I’m afraid all the time. But I think that I’ve learned that on the other side of that fear is all the best things in my life. Everything that has been good in my life, I’ve gotten because I’ve been able to push through the fear that I have.”

Best of Deadline

2023 Premiere Dates For New & Returning Series On Broadcast, Cable & Streaming

SAG-AFTRA Interim Agreements: Full List Of Movies And TV Series

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.