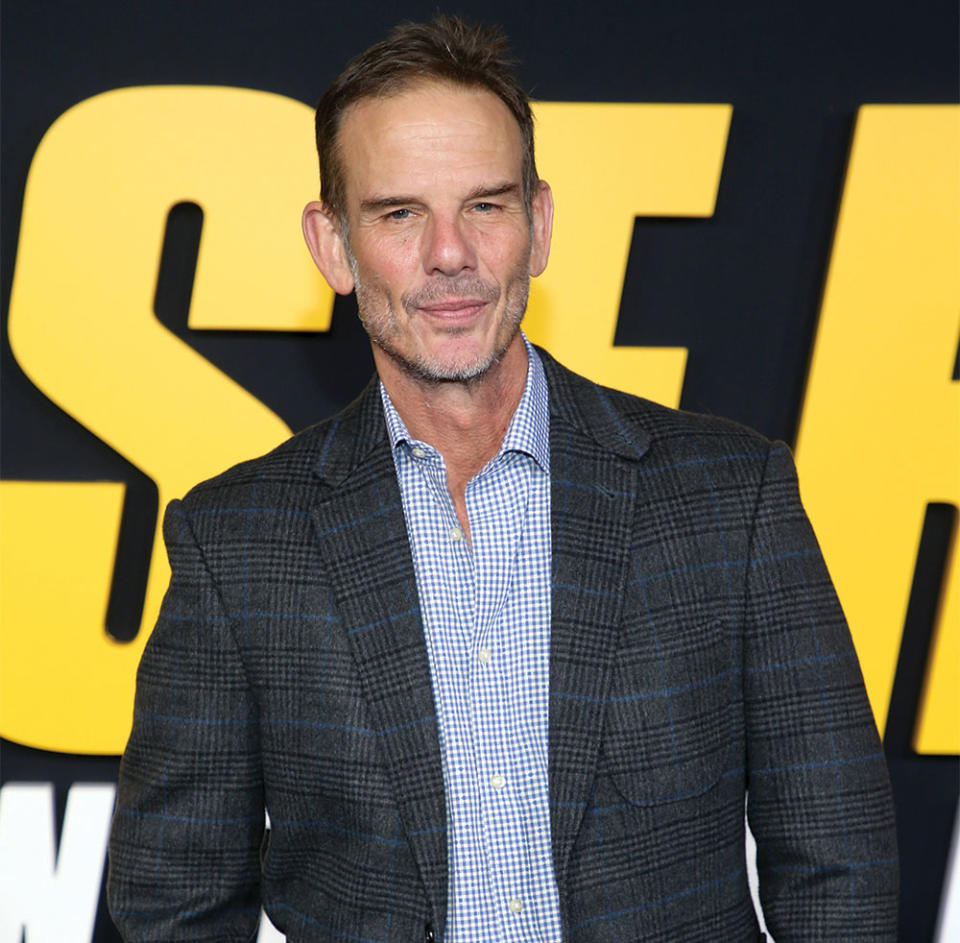

‘Boys in Blue’ Director Peter Berg on Whether Doc Series Changed His View on Policing

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For many years, filmmaker Peter Berg held nothing but fond memories from his college days in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul. “My memory was just one of happiness and real joy, and it felt extremely diverse and inclusive,” the Macalester College alum tells THR — until decades later, when the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin shook the nation to its core. “When I first saw the killing, I was horrified,” he says. “And I was further horrified when I realized that it was in the Twin Cities.”

The aftermath caused Berg to examine how the community had changed in the decades since he’d left. Eager to do something constructive and enlightening, the director-producer of the Friday Night Lights film and TV series journeyed back to helm the four-part documentary series Boys in Blue, taking a deep look at the football program at Minneapolis North High School, set in an already troubled community now rocked to its core in the wake of the Floyd murder — particularly because the team’s coaches also were Minneapolis cops.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Berg found himself chronicling the confusion and complexities faced by the community and its relationship with law enforcement, as well as the inspiring aspirations of the young athletes and the adults trying to help them create a path to a better, brighter future.

“Unfortunately, something really tragic and horrific happened,” says Berg. “Our star quarterback, Deshaun Hill, who was just one of the most beautiful, gifted young men I’ve ever encountered, was murdered three days before we wrapped shooting.”

Berg joined THR to discuss how he and his crew managed to move forward and complete Boys in Blue, with the blessing of the community, the lessons he learned from the experience and the deeper understanding he hopes to convey to viewers.

There’s a candor that everybody — the kids, the coaches, the cops, the teachers — shared, even in such a confusing time for all of them. How did you earn their trust?

I’ve done work in the space that involves people who died: Lone Survivor, Patriots Day, Deepwater Horizon. I’ve experienced going into communities and saying, “We want to tell the story of your loved ones’ lives.” Often these are tragic stories. But early on, I said, “If you let us in, I promise that we will give you our very best, and we will be as honest and truthful as we can, and we will help you tell the story of your lives.”

[The community] let us in, and we developed very deep relationships with these families. Our film crews embedded deeply, not just into Deshaun Hill’s family, but into the coaches’ and into other players’. When Deshaun was killed, we were very confused — it was three days before we were going to stop shooting. Our whole crew assembled, and they were very traumatized. I said, “We’re going to finish telling the story. This is now part of the story. It happened during the time frame that we all agreed that we’re going to be there filming.”

I said, “Let’s not try to make sense of it. I don’t know that it’s something you can make sense of. Let us put it together, tell the story. And before we do anything else, we’ll show it to Deshaun Hill’s parents. We’ll show it to the community, we’ll listen and we’ll gauge how they feel about this.” Which is what we did. Tuesday Hill, Deshaun’s mother, said, “I want people to understand who my son was, and I want people to understand that this is happening all over the country, every day.” People are going to know Deshaun’s name, but there are so many young men who were killed in this country, and we never hear about it. She said, “Go ahead and finish the film — please.”

Tell me how you navigated being the pillar for the crew, and everyone, as the leader of the production.

I was gutted. I knew that the pain that I felt was nothing compared to the pain that parents and siblings and teammates were feeling. It gave me inspiration to work harder. The pain of that community fueled me and everyone else. We were able to channel our pain into work and into anger. We were angry that he had been killed. We were angry at the person who killed him [30-year-old Cody Fohrenkam, who was sentenced to over 38 years]. We used those emotions to bear down and tell the best story that we could and make sure that Deshaun Hill was presented in a way that was truthful to who he was.

Do you have a sense of how this project ultimately changed you as a filmmaker and perhaps as a person?

The first scene of the film is a scene in Deshaun Hill’s living room, and Tuesday is talking to us about her biggest fear, that her son is going to be killed leaving school, going to the bus stop. I truly did not appreciate the fact that what she was saying to us was: “Help. Will somebody please help? This is fucking real. This is not a joke. I’m telling you I’m scared my son’s going to get killed walking to the bus.” Well, her son was killed walking to the bus. After that happened, my understanding of how dangerous life is for young men in so many parts of this country hit me much, much harder. I understand how dangerous it can be to be poor in America. That, for me, was something that I didn’t fully appreciate prior to making this and something that I’m now very cognizant of: how much help people need breaking this cycle of poverty. It’s just not right. It’s not fair. We all, at a minimum, need to acknowledge that it’s very real.

You’ve worked with subject matter involving all kinds of law enforcement. Tell me about the effect that this project had on your relationship and the way that you think about policing.

I know a lot of cops. I’ve seen some horrible police that should have never been allowed to get a badge in the first place. I’ve met some high-quality police officers and know many who I think are the very best examples of what policing can be — cops who possess empathy and decency and are trying to do the right thing and trying to help. I wasn’t surprised to have a lot of admiration for cops like Officer Adams and Officer Plunkett. These, I think, are good men and great cops. I maintain vigilance over cops who aren’t. In Boys in Blue, we take a look at the very best of policing in an honest way that doesn’t sugarcoat it, that doesn’t present these men as saints, as flawless humans, but real people trying to do their best for these kids. I haven’t radically changed my opinion: Cops like Derek Chauvin should be imprisoned, and cops like Officer Adams should be respected and, I believe, applauded.

Interview edited for length and clarity.

This story first appeared in a May stand-alone issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter