Born Slippy: The 'Trainspotting' Soundtrack Turns 20

By Jim Farber

You won’t find a more arresting opening scene in movie history: At the start of Danny Boyle’s caffeinated classic Trainspotting, we see Ewan McGregor’s character, Mark Renton, race down Princess street in Edinburgh, Scotland, chased by advancing security guards. Tearing down stairs and ducking into alleys, Renton seems, at once, scared, defiant, and exhilarated. As he bobs and weaves through the city’s jaunty cobblestones, a voiceover from his character spews the famously sarcastic “choose life” speech, a withering screed against conformity, normality, and even sense.

Together, the scene presents a striking mix of fast-action camera work and charismatic acting. But it would mean nothing without the pummeling beat that propels the scene. Experienced music fans recognized that beat at the time as one Iggy Pop borrowed from Bo Diddley for his then nearly 20-year-old recording, “Lust for Life.” Iggy’s track gave Diddley’s beat a fresh inflection, then married it to a basso profondo vocal and a lyric which encouraged abandon beyond consequence. What better message for a movie about heroin addicts at play?

Though Iggy’s song was already known to the hip set, never before had it meant as much as it did than when matched to this scene in this film. (Video below contains profanity.)

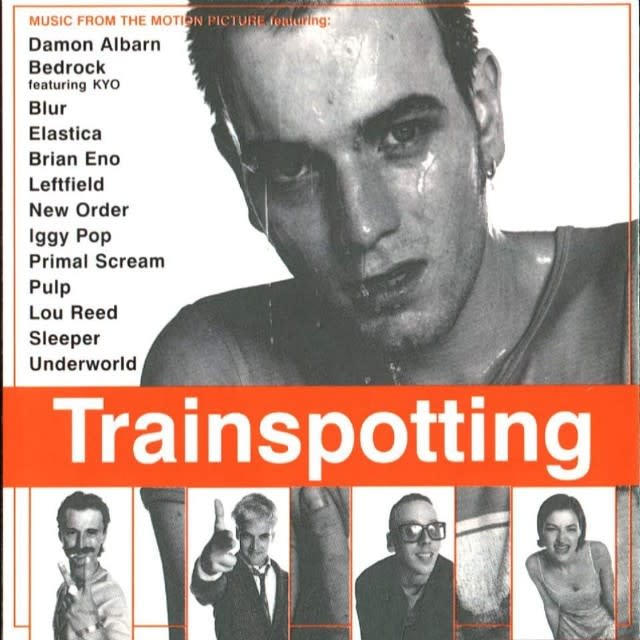

That’s the mark of a great soundtrack. Twenty long years since the Trainspotting film made its mark on youth culture, you can’t see its opening images today without hearing that song. And you can’t hear that song without envisioning those images. Director Boyle kept the connection between sound and vision intimate through all 93 minutes of his film. Which explains why, two decades on, the Trainspotting soundtrack – which is being reissued on limited-edition 180-gram orange vinyl today – remains as indelible as the movie. In the tradition of Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, and Wes Anderson, Boyle used pop songs to give his images a resonance and emotional connection an instrumental score never could.

It helped that Boyle’s setlist tapped into a broader pop-culture trend of the moment. The mid-‘90s release of Trainspotting caught the apex of the decade’s major U.K. craze: Britpop. Bands in that movement, like Blur, Pulp, Elastica, and Sleeper, each offered new recordings for the soundtrack. To their efforts, Boyle added vintage hipster touchstones that the new artists would surely know and love, including “Temptation” from New Order, “Perfect Day” by Lou Reed, and “Deep Blue Day” by Brian Eno, his brother Roger Eno, and Daniel Lanois. Not content to settle on just one Iggy anthem, Boyle folded in the equally propulsive, and transgressive “Nightclubbing.”

Small wonder, Entertainment Weekly dubbed the soundtrack as “Saturday Night Fever for the Ecstasy generation.” The comparison may have been off balance in terms of sales: Trainspotting sold only a cult-scaled 700,000 copies. But in terms of cultural resonance, it nailed it.

The album’s zeitgeisty connection, and relative success, inspired a second soundtrack in October of the next year. The follow-up disc added 15 songs to the earlier 14, including more from role model subversives Iggy and Bowie to buttress ditties from Sleeper, Leftfield, and Underworld.

The bands Boyle included didn’t just catch the peak wave of Britpop, they illustrated that movement’s fresh integration of dance music and rock. The two genres have often eyed each other warily, if not with contempt. But after the “Madchester” rave scene of the late ‘80s, they found common ground. Underworld “Born Slippy .NUXX” in the final scene, and Primal Scream’s 10-and-a-half-minute title track and on the album, offer a perfect gateway, merging the hallucinogenic ambience of the artiest club music with spy-rock themes a guitar fan would admire.

Still, it’s the alchemy of song and image that makes the whole thing click. Renton’s harrowing attempt to go cold turkey in the film needs the shadowy ambience, and the torturous length, of Underworld’s “Dark and Long” to elaborate it. Likewise, the film’s most infamous scene – set in the “Worst Toilet in Scotland” – finds a perfect ironic counterpoint in Eno’s “Deep Blue Day.” In a fever dream, Renton dives head-first into the crapper, where he finds a subterranean universe of druggy tranquility. The image may beguile. But it’s the music that has made it linger.

And now, some Trainspotting fun facts…

–According to Iggy Pop’s manager, Art Collins, the placement of “Lust for Life” in the movie inspired more than twenty other filmmakers to request songs from the star for their movies within six months of its release. “I think it’s because people who were his fans have grown up,” Collins told The London Times in 1996. “Now they run ad agencies and movie studios.”

–The favorite song of Irvine Welsh, author of the novel Trainspotting, isn’t on the soundtrack. It’s “Sunshine on Leith,” a 1999 ballad by the Scottish duo the Proclaimers. The sentimental singalong has become a highlands favorite at both weddings and funerals.

–The Trainspotting soundtrack isn’t available on Spotify, Apple Music, or other streaming services, although fans have cobbled together their own playlist versions.

–The track by Sleeper on the soundtrack, “Atomic,” isn’t an original piece but a cover of a Blondie song from their 1979 album Eat to the Beat.

–Underworld, who contributed to the soundtrack, went on to write music for Boyle movies A Life Less Ordinary, Sunshine, and Trance, along with contributing to the score of the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Summer Olympics, which Boyle directed.

–The ever-elusive David Bowie initially turned down Boyle’s request to use his music in the film. Eventually, he relented, allowing the inclusion of his song “Golden Years.”

–Boyle has a special affection for Eno’s “Deep Blue Day.” He told the Public Radio program “Soundcheck” that the album it comes from, Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks, is “one of the greatest atmospheric albums ever made.” Boyle used music from it in so many projects, Eno once wrote to him and said, “I’ve done other things, you know.”

–Some critics have said that it’s lazy for filmmakers to rely on the kineticism of pop songs for excitement. Boyle answered the charge on the website Le Site. “I just do the best I can,” he said. “It’s up to you to judge whether it’s s— or not.”