Boone County Distilling Company says its bourbon is 'Made by Ghosts'

The people at Boone County Distilling Company like to say the only spirits in their distillery are the drinkable kind.

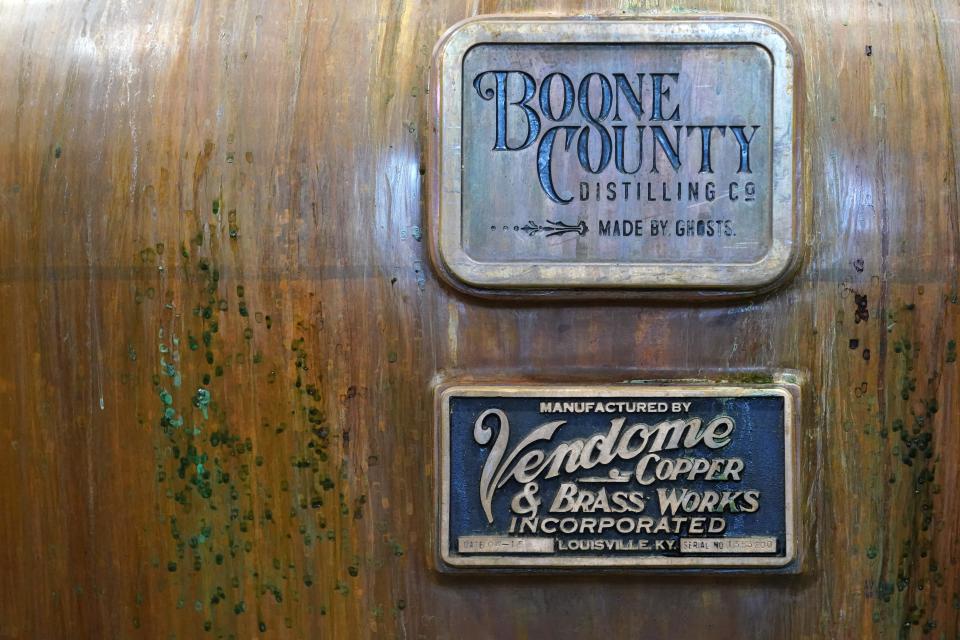

But barrels in the rickhouse suggest something else. Each one is stamped with the words: Made by Ghosts.

It’s a curious slogan for a modern, craft bourbon distillery in an industrial park about 85 miles northeast of Louisville in the Cincinnati suburbs. This isn’t like traveling south to Bardstown where the aging Federal architecture and the black whisky fungus almost beg ghosts to linger. Yet, every single bottle of bourbon filled on Boone County's line has those same spooky words on the label, too.

I wanted to know what it meant.

So about three weeks before Halloween, I made the trip up Interstate 71 hoping to find a ghost story that sent chills up my neck and a smooth pour of bourbon that warmed my belly.

Tour guide Jake Perkins greeted us in the gift shop where black and white portraits of Boone County’s earliest settlers and first distillers hung on the wall. These were ghosts of bourbon’s legacy in Boone County. While they aren’t causing paranormal chaos in the modern distillery itself, the hell they raised in their lifetime certainly left an impression on the area.

The story starts when European Americans began settling what’s now Boone County in the late 18th century, Perkins said. Rev. John Tanner established the Tanner’s Station settlement along the Ohio River in 1791, and later down the line, the community he built would become home to the historic Boone County Distilling Co.

But the 40-acre land grant Tanner developed belonged to an Indigenous tribe and they had used it as a burial ground. The Tanner family settled it anyway, and that’s where the trouble begins.

“Nothing bad really happened to Rev. Tanner himself, but bad things did start happening to [his] sons,” Perkins told our group.

First, Tanner’s 12-year-old son was out in the woods foraging for nuts and berries, and he was killed by a wild boar. Then his 9-year-old son was kidnapped. When he finally returned to Tanner’s Station 24 years later, the son built a house and married, Perkins explained, but the now-grown man had a wanderlust he couldn’t shake.

So he would disappear for a few days or weeks at a time, Perkins said, until finally he never came back again. No one ever knew where he went.

But in recent years, Perkins said, archeologists conducted a dig at Tanner's son's home and found his wife's corpse underneath the house.

She had a hatchet stuck in her skull.

Finally, Tanner’s youngest sons were with a hunting party near what’s now Big Bone Lick State Historic Site. The group had a run-in with an Indigenous tribe and it turned into a multi-day battle. The tribe killed everyone but left one man alive to return to Tanner’s Station and tell the story.

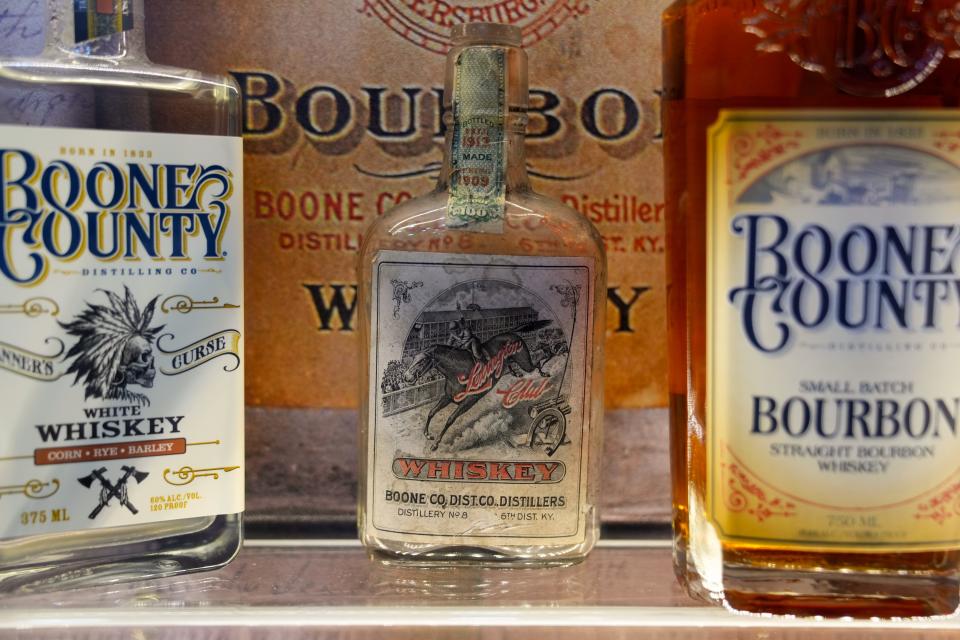

That troublesome, dark series of events is why the distillery named its white whiskey Tanner’s Curse.

Time passed and in the early 19th century, Tanner's settlement was renamed Petersburg. There’s not much left of the town today, Perkins said, but two centuries ago, it was home to a vibrant steam mill.

In 1833, Petersburg businessman William Synder reasoned he could use the same facility to sell whiskey for $5 a bottle instead of flour for five cents a bag. He opened the Petersburg Distillery, which went through several name changes, but eventually became Boone County Distilling Company.

The “ghosts” in this part of the story are Boone County’s earliest industrialists and businessmen, who propelled the area's bourbon industry. That's why portraits of Levy J. Workum, J.C. Jenkins, and James Gaff watch over the fermenters, still, and bottling line. The distillery's artwork also pays special reverence to Lewis Loder, who was known as “The Observer.” Loder was a detailed diarist, and the three to four pages he wrote each day about his community is how the modern distillery knows as much about its namesake as it does today.

By 1880, the distillery in Petersburg was considered the largest in Kentucky. Production hit an all-time high at the turn of the century when the site put out four million gallons of whiskey in 1897, which made it one of the largest distilleries in the country.

Until trouble strikes, again.

In 1901, Boone County Distilling Co.'s booming success attracted the attention of the mob in Illinois.

“They would go to distilleries and bully them, just like the mob would do with other local businesses,” Perkins told our group. “They would show up one day to purchase the distillery and give them a very low offer.”

When the businesses declined, the options only got worse.

“They would show up the next day with a wagonload of dynamite, and an even lower offer,” Perkins said.

That’s how the bustling distillery in Petersburg sold for $500,000, which was an insult to what its production was at the time.

From there production dips immensely. Turns out the mob members were masters at threatening, but not wonderful at running a distillery.

“They also were trying to squeeze as much money as they could out of the alcohol industry,” Perkins explained. “So they would lower production rates, they tried to increase demand, and they tried to sell things at much higher rates.”

The mob drove the business into the ground and by 1910, the old distillery site shuttered for good, and eventually, it was reconfigured into the Petersburg jail.

Whiskey wasn’t bottled legally in Boone County again for more than a century when the modern distillery opened in Florence in 2015. The young distillery isn't using the company’s original recipes or even operating on the old distillery grounds.

Even though the owners adopted the historic name, they weren’t able to formally use the old, coveted, single-digit No. 8 that Boone County Distilling Company once had. Kentucky distilleries are numbered based on their order of origin, and modern distilleries usually have five digits in them, unless they've been able to reclaim a historic number.

In a tongue-in-cheek way, they slip in that “No. 8” whenever they can. If you look at a bottle of Boone County’s bourbon the Os are stacked to make a figure eight. The company proofs its spirits at oddly specific numbers, too, such as 94.8. The current distillery is registered at 20,028, again, with the last digit nodding to that No. 8.

The company makes bourbon in the spirit of the founders, Perkins explained, even if there aren't necessarily any ghosts onsite.

It would have been nice to return to the old distillery ground, Perkin mused, but between zoning laws and just how far out Petersburg is, it made more sense to do it 25 miles to the southeast in Florence.

And perhaps, that’s a good thing.

The modern Boone County Distilling Co. has already won several national awards, filled its rickhouse to capacity and is looking for more ways to expand. Business is booming.

And while telling the story of the Tanner family, the original distillery and the mob might make for an interesting tour — I think it’s a relief the only true spirits at Boone County are the ones in the bottle. Things are going far too well for the company and the Kentucky bourbon industry as a whole.

Being "Made by Ghosts" is one thing, but somehow I don’t think anyone wants to wake a 230-year-old curse from its slumber.

Features columnist Maggie Menderski writes about what makes Louisville, Southern Indiana and Kentucky unique, wonderful, and occasionally, a little weird. Sometimes she writes about bourbon. Say hello at mmenderski@courier-journal.com. Follow along on Instagram and Twitter @MaggieMenderski.

Holiday gift ideas: Getting a start on holiday shopping? Here are 5 bourbons (and one hard coffee) to gift

More in KY bourbon news: 'Unicorn' bourbons estimated to sell for $30K at Speed Art Museum spirits auction

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Northern Kentucky distillery says its bourbon is 'Made by Ghosts'