How a New Book Unearths the Secrets of ‘The Shining,’ from Stanley Kubrick-Shelley Duvall Clashes to a Werner Herzog Set Visit

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Lee Unkrich was 12, he saw “The Shining” for the first time. He remembers less from the screening than what happened shortly afterward, which set in motion a lifelong obsession with Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece of horror.

On his way to summer camp, Unkrich bought the movie tie-in edition of Stephen King’s novel. “There were photos of Wendy cooking breakfast in the kitchen,” he tells Variety. “I realized that wasn’t a scene that was in the movie. And that got a bug in my head — I wanted to know more about that world.”

More from Variety

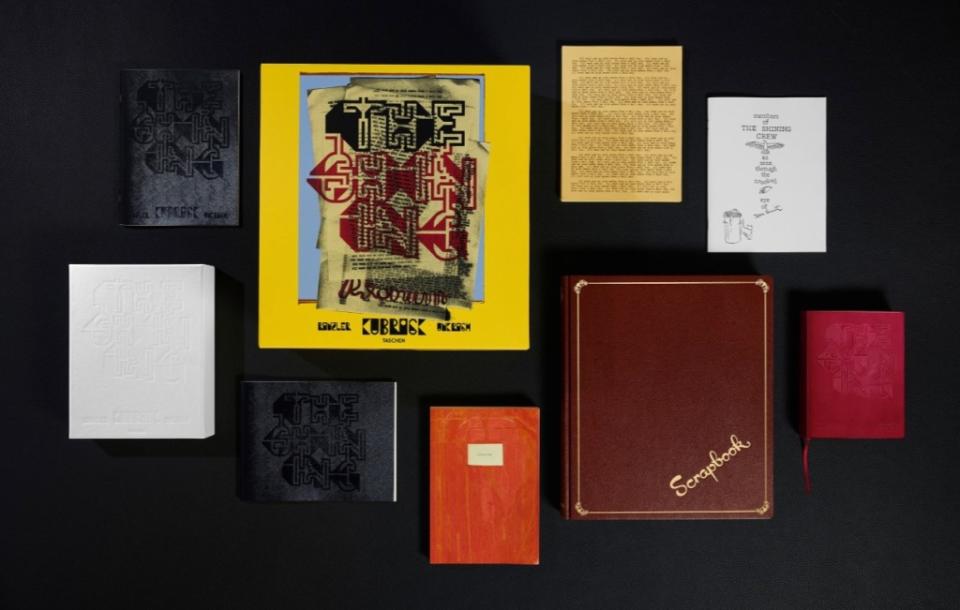

Taschen Releases 2,000-Page 'Definitive Compendium' to 'The Shining' for $1,500

Leon Vitali, 'Barry Lyndon' Actor and Personal Assistant to Stanley Kubrick, Dies at 74

For Unkrich, a 25-year Pixar veteran, that deleted scene would beget decades of collecting Kubrick ephemera, a stream of Easter eggs in his work from “Toy Story 2” to “Coco,” a website cataloguing his findings, and now, “Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining,” a 12-years-in-the-making, 2,200-page account of the creation of Kubrick’s film that Taschen is releasing March 17.

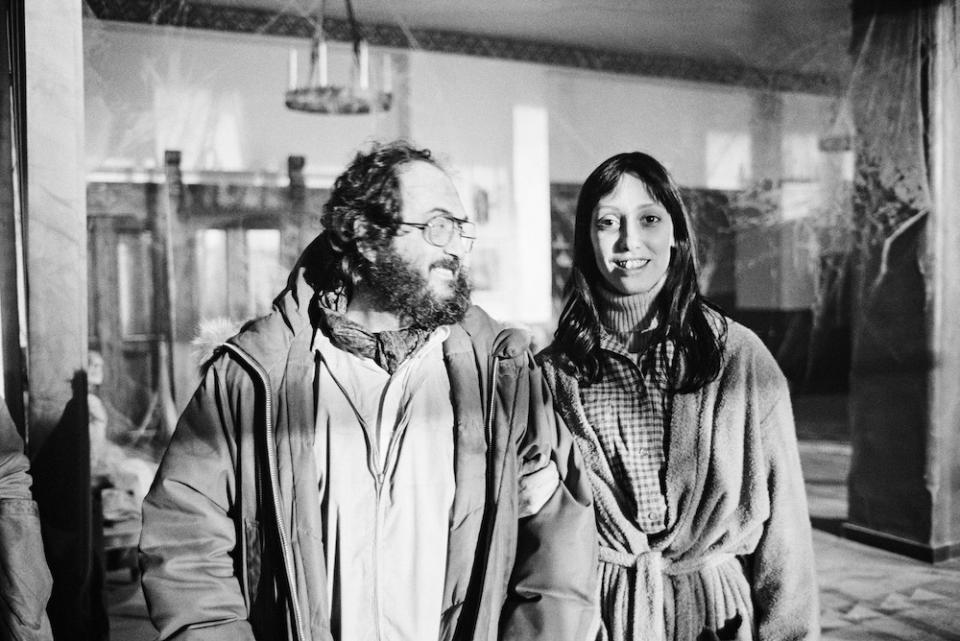

Armed with unfettered access to Kubrick’s archives, Unkrich worked with the late J.W. Rinzler to collect hundreds of photographs, production details and interviews with virtually every available cast and crew member. The result is a road map through the mazelike history of one of the most closely scrutinized movies of all time. “Most people have their needle-drop sound bites and stories that they’ve told over the years,” Unkrich says. “I would show them photos, and that’s when the stories just started flowing.”

For Dan Lloyd, who was just 4 when he auditioned for the role of Danny Torrance, the book crystallized memories he wasn’t sure actually occurred. “There’s a picture of me and my stand-in and Leon [Vitali, Kubrick’s longtime assistant, who died in 2022] working on walking backwards in my footprints for when Danny tricks Jack in the maze,” Lloyd says. “To the 5-year-old brain, it feels like months we worked on that.”

Though his memories of the experience are faint, Lloyd says that everyone on set was fiercely protective of him, especially when it came to shooting the most frightening scenes. “I’d estimate we were there in England for over a year, but I think I only worked probably 60 days. And there were definitely days where I was not supposed to be at the studio,” he recalls. “Not just on set, but just don’t come in — even by accident don’t drop by — because they were going to be doing something scary.”

Unsurprisingly, Lloyd’s most vivid recollections are of the kid stuff he was able to do that tested the usual boundaries of parental permissiveness, though he says his parents were always there to supervise.

“I have pretty good memories of riding the trike — I remember being excited because I was riding inside,” he says. “They kept trying to figure out how they were going to do the shot and it couldn’t be a dolly shot because of the tracks. But because they were experimenting, I got more and more time to ride around.”

Unkrich says that Vitali was especially helpful in unearthing bits of lore that had never been publicly discussed.

“I had a photo of Danny and his brother sitting with Vivian Kubrick on the back lot at Elstree, and there’s a guy in the background. It wasn’t until I was sitting with Leon and I brought that picture up and he said, ‘That’s Werner Herzog,’” he recalls. “That then led to a whole story about Werner Herzog being the person who convinced Stanley that the sound of Danny’s trike going over the hardwood floors and the carpet back and forth actually sounded cool because Stanley was worried that it didn’t sound good.”

Garrett Brown, the inventor of the Steadicam who’d shot Sylvester Stallone running up the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art in John Avildsen’s “Rocky,” was just starting to cultivate an army of camera operators capable of using the device when Kubrick tapped him to capture the corridors of the Overlook Hotel with liquid smoothness.

“Stanley had had a 2CV Citroën stripped down — took the engine and the body and everything off of it so all you had was a seat, a steering wheel, and a little platform in the back for the camera,” Brown says. “Because the suspension is so amazingly sloppy, he was hoping that if you push it down the corridors, it would allow the camera, but the results from that were disastrous.”

“There was really no choice but the Steadicam to navigate those huge spaces,” he continues. “[But] it got absurd at times in the maze. If a viewer knew what we were doing, they would be astounded. I was trudging through dairy salt eight inches deep with Styrofoam above thousand-watt lights on thoroughly dried-out pine needles. We were all terrified of fire the whole time, crunching along in my continually rotting boots because of the salt in a hundred degrees Fahrenheit. And it was oil smoke, now illegal, but then, legal. And we breathed it for three months to make that mist. And then you look at the final shot, and gosh, it looks amazing.”

Reminiscing about the production also reminded him of a few jobs he didn’t take. “I turned down [‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’] for very poor reasons in hindsight, and got [Spielberg] an operator. When I saw the film with my son in the theater, I almost had tears running down my face,” he says regretfully. “Steven Spielberg did forgive me and I worked for him later, but I made a few notoriously bad decisions like that.”

Through overlapping interviews, Unkrich explored elements of the filming that have since taken on mythic proportions, such as the relationship between Kubrick and Shelley Duvall, whose discord in Vivian Kubrick’s making-of documentary has come to symbolize the director’s exacting requirements for his collaborators. Diane Johnson, Kubrick’s co-screenwriter, indicates that the friction led the filmmaker to focus more on Jack Nicholson’s frustrated writer, Jack, and to treat Duvall’s Wendy more reductively than in King’s book — and indeed than Johnson would have liked.

“The reason that [Wendy’s] not more developed in the script finally was because he didn’t get along with Shelley Duvall,” Johnson says. “They just clashed. And so he removed a lot of her scenes. The dialogue that I wrote for Wendy was pretty much [taken from] Stephen King, in which she talks like a normal person and has interesting perceptions and so on. And the reason that she comes off as just so kind of hysterical is to do with Kubrick and Duvall.”

Rather than litigating the various accounts of what happened in the pages of the book, Unkrich attempted wherever possible to speak directly to the individuals involved, especially Duvall, whom he interviewed even before she sat down for her controversial conversation with Dr. Phil in 2016. “Ultimately, the most important person to hear from was Shelley herself,” he says. “And Shelley loves Stanley.”

“I think of it like that story about all the blind men touching an elephant, and each one only has one part, and they’re describing what they think they’re touching and none of them have it right, because they’re not seeing the totality,” he says. “And I think that’s what happened with that film, honestly, is that people just assume that the whole thing must have been harrowing like that for her.

“Shelley will tell you that it was a very difficult shoot. And she’ll also say that she didn’t necessarily agree with Stanley’s tactics at times for getting a performance from her,” he says. “But she admits that he got an amazing performance out of her.”

On the other hand, Unkrich says there were a few details for which he never got the “real” story. “The odd moment of the guy in the bear costume giving the guy a blowjob on the bed when Shelley’s running around? No answers on why he chose to put that in,” he reveals. Even Johnson says she doesn’t know where it came from: “It’s not in King. It was nothing that we ever discussed — it came out of Kubrick’s imagination, as far as I know.”

Though Johnson had nothing to do with that image, or the iconic shot of the blood flooding out of the elevators — “That was already in his mind, or maybe even filmed, so I wasn’t called upon to visualize anything,” she says — her involvement started when Kubrick became interested in what she calls her “theoretical interest in the early 19th-century Gothic novel.”

“And then we started talking about contemporary ghost stories and horror literature in general,” she says, adding that this more informal approach served their collaboration, especially since she had no prior screenwriting experience. “Stanley was very tutorial… one of the things that interested him was the outline — a version of the script as a kind of shorthand, to analyze the dramatic development, the suspense, the denouement, all that.”

In retrospect, Johnson says she was shocked by the ability of the film — and the medium — to transform her ideas into what have become indelible cinematic moments. “I was so unaware of the magnifying effect of film,” she says. “Where somebody says, ‘No,’ on the screen, it’s powerful. When you’re writing a novel it’s just a word. So I was a little bit overcome to see it on the screen.”

With plans to commemorate the book release with a March 17 screening of “The Shining” at the Academy Museum, Unkrich says he feels a sense of catharsis, but not necessarily one of completion. “I’ve already heard one story, and I’ve found one thing visually since we finished the book that I’m hoping I can maybe get into the trade edition or a later edition,” he says. But Unkrich is most gratified by what the experience taught him about his filmmaking idol.

“The biggest thing that I took away, and this is more kind of for me as a filmmaker, was Stanley’s humanity,” he says. “Everyone put Stanley up on this pedestal as being this brilliant filmmaker, which he was, of course. The reality was, he struggled every step of the way. He couldn’t sleep because he was worried there was a better idea out there that he hadn’t stumbled upon. And I could relate to that because I’ve been through that on all of my films. And I liked that I saw a person, and not just an icon.”

Best of Variety

Final Oscars Predictions: Animated Short - Will the Academy Go for 'The Boy' or 'Dicks?'

Final Oscar Predictions: Documentary Short - Will the Academy Go for Malala or 'Elephants?'

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.