New book explores lifestyle of the rich and famous Wilmingtonian Pembroke Jones

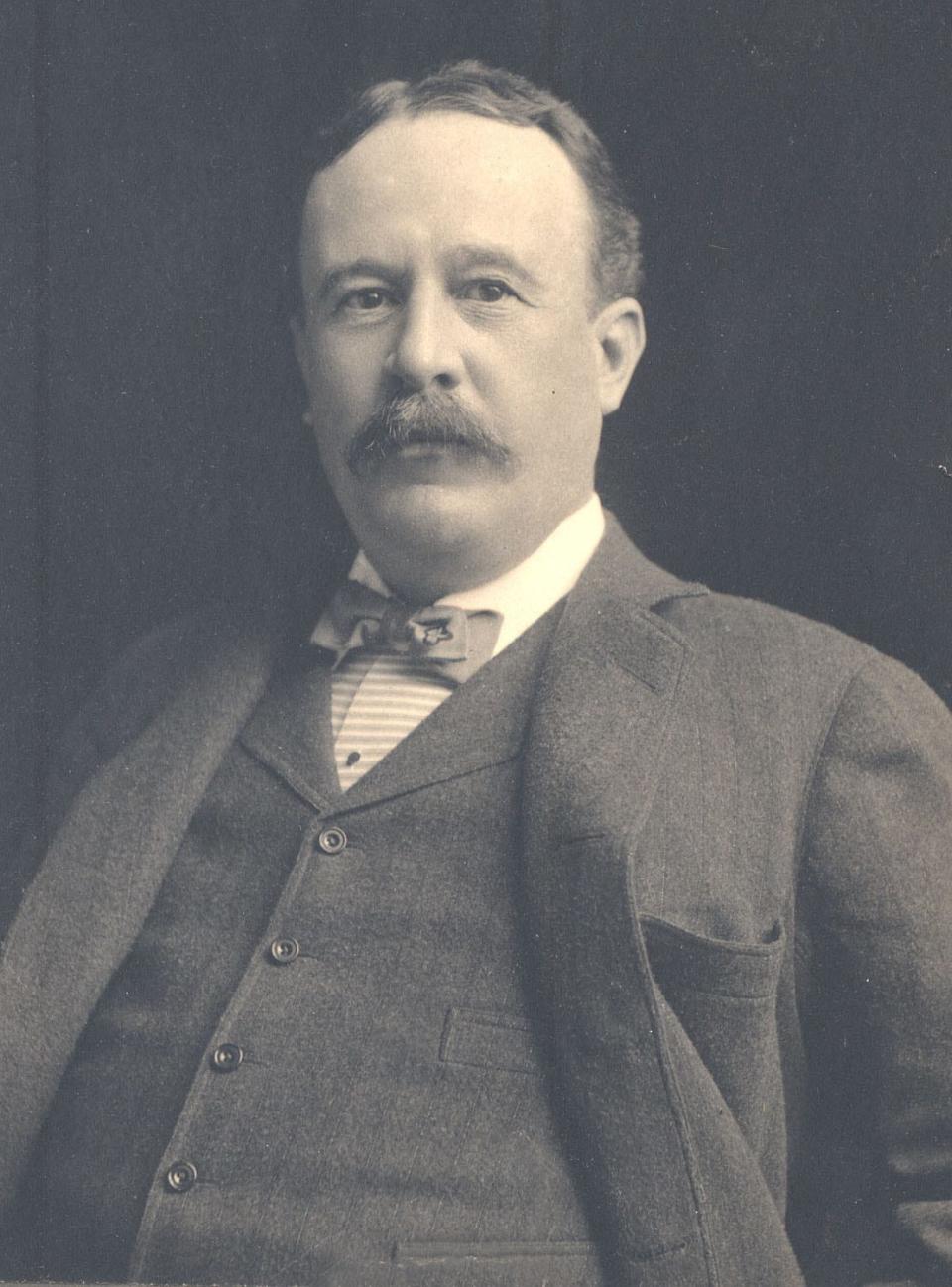

One of the most colorful characters in Wilmington's history is Pembroke Jones (1858-1919), a millionaire and more-or-less certified member of "The Four Hundred," a who's who of the rich and famous from the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Jones made a fortune in rice milling by the time he was in his early 30s and apparently augmented that with canny railroad investments that were no doubt advised by his good friends, Henry Walters, longtime president of the Atlantic Coast Line railroad. (Walters actually lived with Jones and his wife, Sarah, for many years; three years after Jones died, Walters and Sarah were married.)

Once he had his money, Jones set about to enjoy it. He and his wife had a mansion at Newport, Rhode Island, where Jones joined in the yacht races. (He served a term as commodore of the Carolina Yacht Club). They had a home in New York and were frequently off to European tours and Mediterranean cruises.

They generally wintered in Wilmington, where Pembroke and Sarah amassed a huge estate along Bradley Creek and what would become the Intracoastal Waterway. They built his-and-hers mansions, with Sarah generally staying at "The Shack," at Airlie, which boasted 38 bedrooms, dinner seating for 80, a ballroom and an indoor tennis court.

Over at Pembroke Park, where the gated Landfall community is today, Pembroke Jones built an Italianate villa called The Lodge, where he hunted foxes, raccoons and just about anything else. Landall residents having trouble with deer can probably blame Jones; he imported a large herd for sport.

Lots of books make passing references to the Joneses, but there hasn't been a proper biography until now. Retired Wilmington businessman William Campbell Hunter has done a workmanlike job in "Keeping Up With the Joneses." Although not an academic historian, Hunter seems to have tracked down every single newspaper clipping about the Joneses and mined them for all they're worth.

About the title: The late Susan Taylor Block was convinced that Pembroke and Sarah's social exploits were the source of the phrase, "Keeping up with the Joneses." The phrase is often traced to a newspaper comic strip of that title by Arthur "Pop" Momand, launched in 1913.

Hunter believes the Joneses were the model, too, and marshals plenty of circumstantial evidence. Certainly, Pembroke and Sarah Jones entertained the cream of society and attracted many of them south to Airlie. Several Vanderbilts (including George, who built the Biltmore estate outside Asheville) showed up. Once, the Joneses, who had a box at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, brought the great tenor Enrico Caruso down for a private recital at the Lodge. Caruso's pianist was unavailable, so Pembroke Jones hired the lady who played piano for the silent movies at The Bijou Theatre downtown.

Not everyone agrees on the origins of "keeping up with the Joneses," and Pembroke and Sarah aren't among the top contenders outside Wilmington. Some sources think the origin lay with novelist Edith Wharton's wealthy father; others track it to Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones, whose Hudson Valley mansion, Wyndcliffe, built in 1853, was much envied and much copied.

One connection is certain: The Joneses daughter, called "Sadie," married the architect John Russell Pope, who designed the National Gallery in Washington. For his father-in-law, Pope designed and built a "Temple of Love" on the grounds of the Lodge, which resembles a sort of first draft for Pope's masterpiece, the Jefferson Memorial in Washington.

For all his diligence, Hunter's work falls victim at times to monotony. The Joneses give a party. Then they give another one. Then they come back to Wilmington and throw a party here. And so on, and so on.

Perhaps for this reason, Hunter tends to veer off to spend time on subjects who had only limited contact with the Joneses, such as Teddy Roosevelt's acid-tongued daughter, Alice; Mary Lily Kenan (sister of William Rand Kenan Jr.), who married the oil and railroad baron Henry Flagler and then died under mysterious circumstances; or Minnie Evans, the "outsider" artist who was the longtime gatekeeper at Airlie and who worked as a maid at The Lodge as a young woman.

Neither The Shack nor The Lodge survive today. (Hunter was one of a horde of young people who snuck into the Lodge's ruins back in the 1950s and early '60s.) Pembroke Jones actually left little footprint on his hometown; "Pembroke Jones Playground," which is now largely tennis courts at New Hanover High School, is one of the few traces.

Sarah Jones, however, did better. Hiring the German landscaper Rudolph Topol, she developed Airlie into a garden showplace. Airlie Gardens is now owned, preserved and maintained by New Hanover County.

Book review

'KEEPING UP WITH THE JONESES: Pembroke Jones and Friends of the Gilded Age'

By William Campbell Hunter

By the author, $35. Hunter is placing copies of "Keeping Up With the Joneses" with local bookstores and museums. Copies may be ordered by emailing him at williamchunter832@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: Pembroke Jones biography, with Airlie Gardens, Landfall in Wilmington