New book delves into the remarkable life of an enslaved man who lived in Wilmington

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

North Carolina might be more closely associated with the Grand Ole Opry than with grand opera. This year, however, Greensboro native Rhiannon Giddens shared the Pulitzer Prize for music for her opera "Omar."

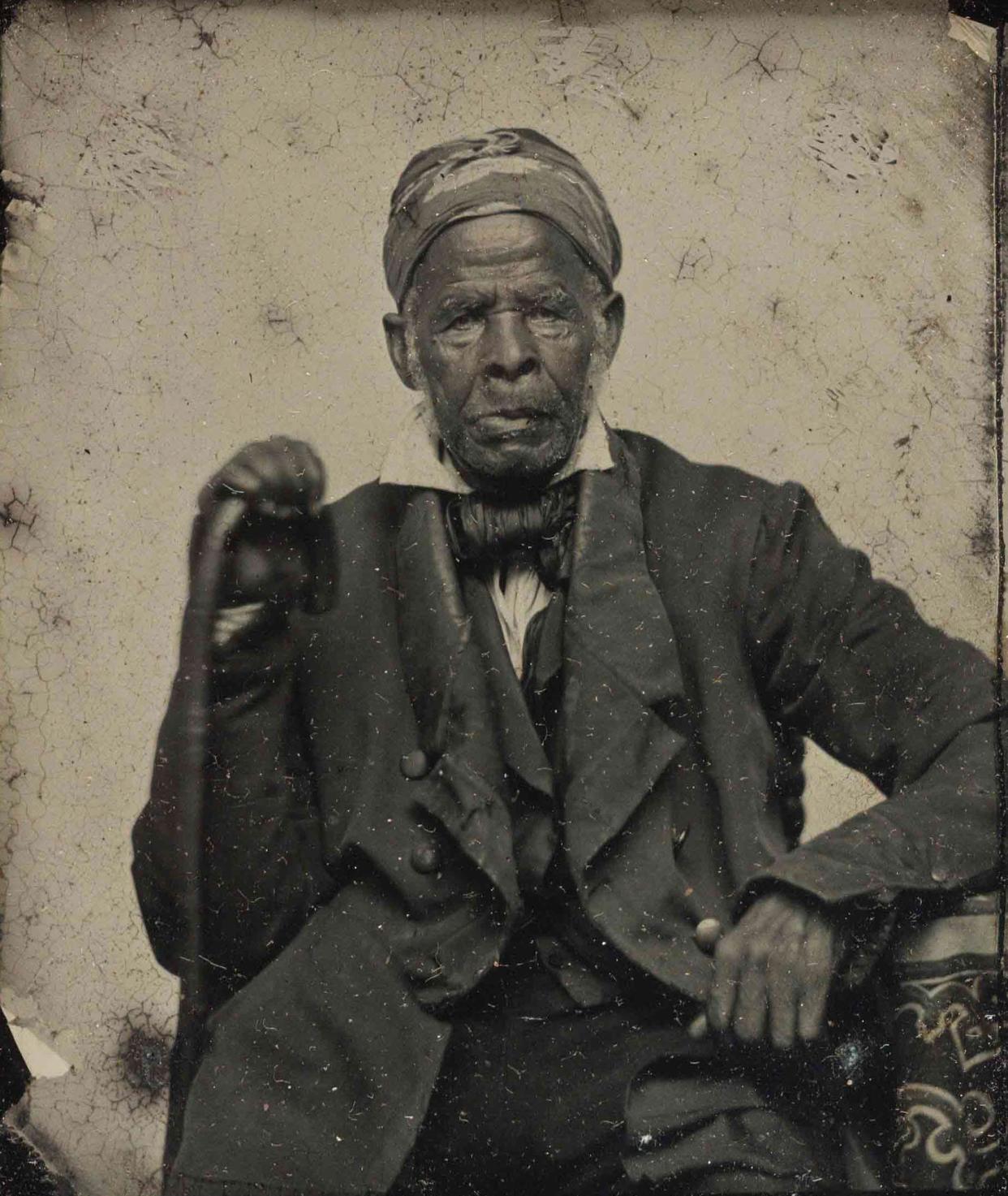

The subject of that opera lived in Wilmington for many years in the 1800s: Omar ibn Said, one of the most remarkable African-Americans from the antebellum era.

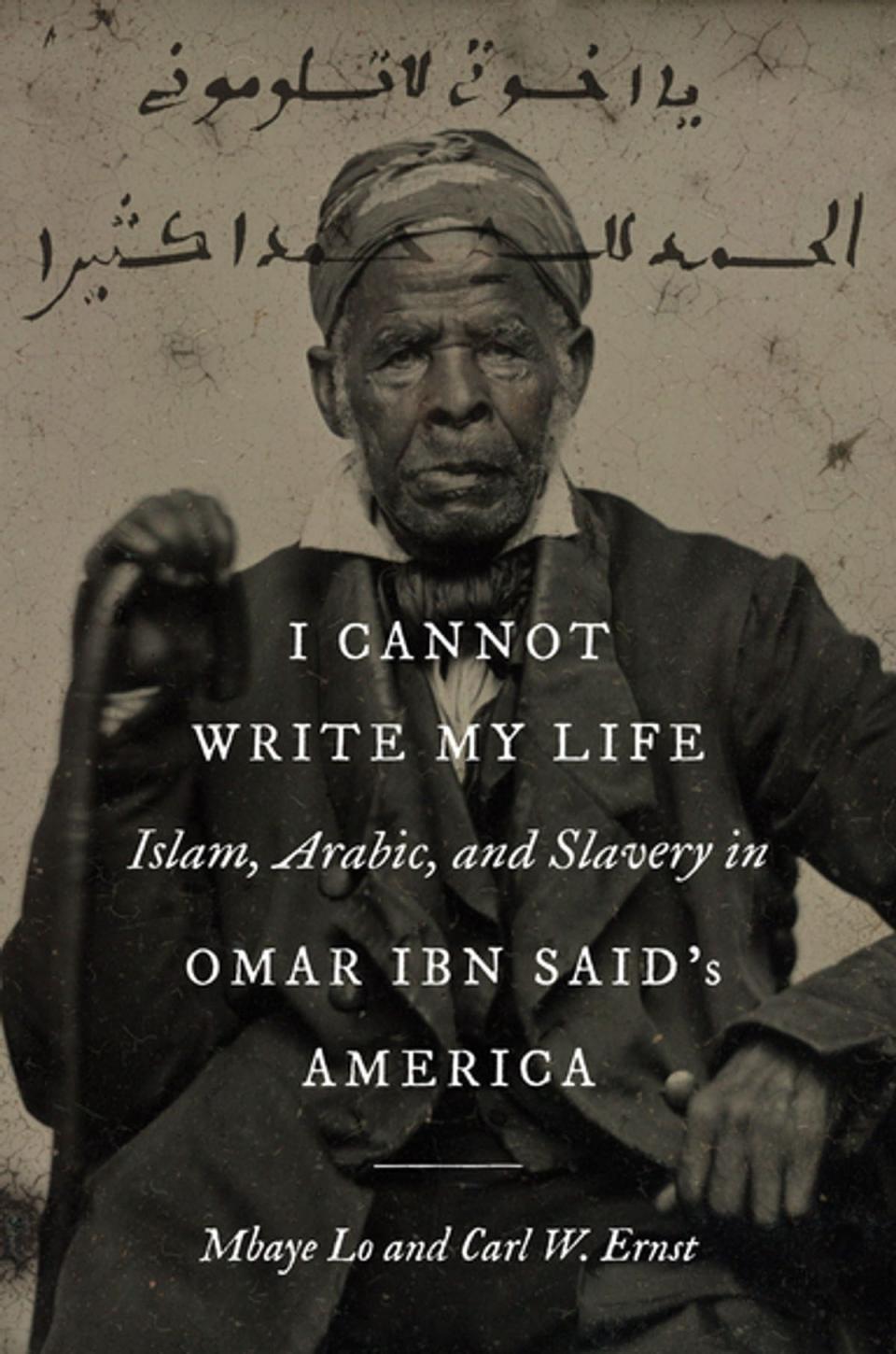

Now, a new book takes a closer look at what ibn Said wrote, including his remarkable autobiography. Its ironic title: "I Cannot Write My Life," from ibn Said's humble disclaimer.

In fact, authors Mbaye Lo and Carl W. Ernst argue, white historians have been misreading it for years.

Born around 1770 to a large family in what is now Senegal, ibn Said spent a quarter century studying the Quran and Islamic theology, law and literature. He seems to have been a respected teacher and cleric. In 1807, during a war, he was captured by non-Muslims and sold into slavery. After a six-week sea voyage, he wound up on the auction block in Charleston, S.C.

Ibn Said was bought by a cruel master who tried to put the short, slight scholar to work picking cotton. In 1810, ibn Said ran away, was captured in Fayetteville and put in the county jail.

There, he attracted attention by writing Arabic passages on the jailhouse walls with charcoal from the fire. As it turned out, the sheriff's son-in-law was one James Owen, a prominent Bladen County planter. The Owen family had clout. James Owen was a militia general and former congressman; his brother, John Owen, was the first North Carolina governor from the Whig Party.

Owen arranged to buy ibn Said and kept him thereafter as a sort of human show horse or house pet. He was not put in the fields; he wore suits, shirts and ties handed down from the Owen brothers, and his diet was rather better than most other slaves.

James Owen showed ibn Said off to scholars and ministers, and he drew national attention. Francis Scott Key, lyricist for "The Star-Spangled Banner," arranged to send him a copy of the Christian Bible in Arabic. Owen also allowed ibn Said to write.

Over the years, the story of ibn Said -- who was also called "Prince Moreau," "Omerah" or "Uncle Moro" -- was romanticized and prettified by white writers. He was described as an Arab prince, which he almost certainly was not.

In 1820, ibn Said supposedly converted to Christianity at the local Presbyterian church. Almost all modern scholars, including the authors of this book, believe that conversion was a sham to please his masters. For the rest of his life, ibn Said continued to quote the Quran and Islamic authors. He seems to have paid relatively little attention to that Arabic Bible, mastering just a few passages, such as Psalm 23, to impress the white folks. His margin notes reflect a Muslim viewpoint.

White authors before the Civil War, and for decades afterward, tended to tell the story of "Prince Moreau" to show how benign slavery was. His conversion was seen as the triumph of the True Faith.

Lo, an associate professor of Middle Eastern studies at Duke, and Ernst, a Kenan professor emeritus in the religious studies department at Chapel Hill, spend a long time hacking through this undergrowth with a metaphorical machete.

Yes, ibn Said always expressed gratitude to the Owen family and pronounced James and John Owen to be "good" men. He certainly saw how slavery could have been worse for him. But it is not true that he stayed in slavery voluntarily out of loyalty to the Owenses. As early as 1819 and for decades thereafter, he expressed a desire to return to Africa. Unfortunately, his pleadings were in Arabic -- ibn said never learned to write English -- so no one paid attention.

Lo and Ernst devote a close reading to ibn Said's texts and prove he was doing more than reciting the Quran from memory. As a scholar, ibn Said was well read -- Egyptian grammar, Islamic law, Sufi poetry -- and his autobiography and sermons were peppered with allusions to other works that earlier translators completely missed.

From the annals of history An opera based on the life of an enslaved Wilmington man has won a Pulitzer Prize

Living with the Owen family in Wilmington from 1837 until the Civil War, he continued to write what the authors call "talismans" -- short passages of the Quran or other Arabic works -- on long scraps of paper. Some of these he posted on trees. Others he gave or sold to other slaves, who kept them as magical. Some of these talismans are still preserved in the New Hanover County Public Library's North Carolina Room.

"I Cannot Write My Life" is not recreational reading. Ordinary readers might first want to consult Allan Austin's "African Muslims in Antebellum America," with its chapter on ibn Said.

Still, it makes a strong case for the persistence of Islam among African-American slaves and points to the hazards of judging the non-Western world with Eurocentric prejudices.

Book review

'I CANNOT WRITE MY LIFE: Islam, Arabic and Slavery in Omar ibn Said's America'

By Mbaye Lo and Carl W. Ernst

Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, $24.95 paperback

This article originally appeared on Wilmington StarNews: I Cannot Write My Life by Mbaye Lo and Carl W. Ernst, on Omar ibn Said