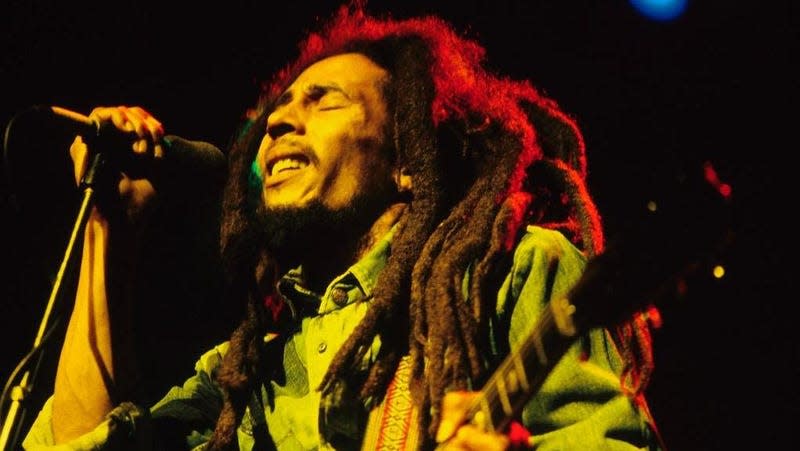

Bob Marley's 25 greatest songs, ranked

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Bob Marley’s life finally hits the big screen this week in the form of Bob Marley: One Love. In his 36 years, Marley lived a life so rich and tumultuous, not all of it can be distilled into a biopic. Similarly, he produced more great music than could be contained on Legend, the posthumous 1984 compilation that helped cement his image as a Rastafarian mystic and reggae outlaw.

One of the best greatest hits albums ever assembled, Legend painted a vivid, colorful portrait but it wasn’t complete: it deliberately favored his lighter later material, leaving the tougher work of the Wailers to languish on LPs and CDs. Those early records, when the Wailers featured Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer, are crucial to understanding the impact and legacy of Marley. They’re featured here, along with selections from Legend, on a list of 25 essentials that tell Bob Marley’s story as thoroughly as One Love itself.

25. “Small Axe” (1971)

Simultaneously a statement of solidarity for the oppressed and a critique of the insular Jamaican music industry, “Small Axe” helped establish Bob Marley & the Wailers’ status as outsiders: no matter the interpretation of the song, they stood as Davids poised to slay a Goliath. Originally released as one of the many, many singles Bob Marley & the Wailers issued in 1971—a good chunk of those were produced by the legendary Lee “Scratch” Perry—“Small Axe” was given a slower revision on Burnin’, which showcased the sinewy swagger of the Wailers.

24. “Concrete Jungle” (1973)

“Concrete Jungle” drew a vivid portrait of the dense urban housing projects of Trenchtown, the sound of the city conveyed by an elastic, sultry groove. The rhythms were slower on the song’s original 1971 single, and while they weren’t fast when the Wailers recut the song as the opener to Catch A Fire, the slight increase in speed helped draw a direct line between Jamaica and the soul emerging from the American South in the late 1960s.

23. “Kinky Reggae” (1973)

A travelog of sorts, “Kinky Reggae” follows the adventures of a drifter who just can’t settle down, no matter what temptation comes his way. His restlessness isn’t given urgency on Catch A Fire, as the Wailers lope and ramble, creating an ambling groove ideal for a wanderer. Marley wound up reversing course somewhat when he revisited the tune years later on the live Babylon By Bus, giving it pronounced muscle.

22. “Lively Up Yourself” (1971)

“Lively Up Yourself” blurs distinctions between reggae and sex, with Bob Marley urging romance that starts in the morning and runs into the evening; whenever he sings about rocking or skanking here, it could be something done on either the bedroom or the stage. Like many songs the Wailers cut in the early 1970s, they revisited the song again on Island Records, giving it a steamier, more urgent reading on Natty Dread.

21. “Exodus” (1977)

Riding its core groove for nearly eight minutes, “Exodus” creates a hypnotic sway that suggests dub without quite venturing out into space. It also hints at disco without relying upon a heavy backbeat. Marley pairs an interior spiritual quest with these urgent rhythms, splitting the difference between the secular and spiritual in exciting ways.

20. “Punky Reggae Party” (1977)

Embraced by the rock ruling class early in his career, Bob Marley didn’t initially find punk rock appealing. Hearing the Clash play reggae changed his mind and, soon enough, he called out those punk rockers and other upstarts on “Punky Reggae Party.” Here, Marley reversed the equation, bringing a nervy new energy to his reggae.

19. “Guava Jelly” (1971)

Picking up a thread left hanging by “Stir It Up,” “Guava Jelly” is an outright sensual song. An early hit from Bob Marley and the Wailers, it reached beyond Jamaica; the song was covered both by Johnny Nash and Barbra Streisand. Grounding “Guava Jelly” in a rocksteady beat, the Wailers provide supple support for a smoldering performance from Marley, who never sounded as seductive as he does here.

18. “Trenchtown Rock” (1971)

Crafted as a salute to the Kingston neighborhood of Trenchtown, commonly acknowledged as the birthplace of reggae, “Trenchtown Rock” also serves as a sterling example of reggae’s virtues. Powered by a tough, lanky groove underpinned by Bob Marley’s scratching guitar, “Trenchtown Rock” set the pace for reggae in the 1970s, the pure rush of sound proving the thesis of Marley’s opening line: “One good thing about music, when it hits you, you feel no pain.”

17. “Duppy Conqueror” (1971)

Duppy is Jamaican parlance for evil spirits or ghosts, so it follows that the harmonies on “Duppy Conqueror” are slightly spectral. These wails color a sprightly rhythm in its original 1971 incarnation, where producer by Lee “Scratch” Perry conjures a feeling that’s grounded even when it’s straining toward space. The version the Wailers cut for Burnin’ opens up the song by slowing the pace slightly and sharpening the execution, giving it welcome—if not quite necessary—grit.

16. “Jamming” (1977)

“Jamming” finds Bob Marley and the Wailers sanding away the rougher edges of their music, creating an ebullient bounce that would become the foundation of the Sunsplash reggae that swept through North America during the remaining years of the 20th century. Where his followers sweetened things a bit too much, Marley retains a sense of grit in the grooves on “Jamming,” which is the key to the record’s enduring appeal.

15. “War” (1976)

One of Bob Marley’s key protest songs, “War” has a stark, nervy arrangement that gives the track a sense of urgency. The core of the song lies in an address Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie presented at the United Nations, a speech that drew a clear connection between the denial of human rights and the uprising of war. Marley massages these words with a supple melody and groove that nevertheless has a strong, unyielding center of gravity.

14. “Positive Vibration” (1976)

The keynote on the Rastaman Vibration and Bob Marley’s first true hit in America, “Positive Vibration” wears its sentiments plainly in its title: this is a song about finding sustenance in good vibes. The cheerfulness of “Positive Vibration” signals a palpable shift within Marley’s music: he’s losing some of the gritty gravity of the original Wailers, and gaining a bright, infectious energy.

13. “Simmer Down” (1965)

The first single from the Wailers, “Simmer Down” found Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer, and Junior Braithwaite supported by the Skatelites, the pivotal group in 1960s ska. A call to ease tension among the rude boys of Jamaica, “Simmer Down” expertly follows the contours of ska while showcasing the kinetic vocal chemistry of the Wailers: it’s easy to see why it became Marley’s first number-one hit in Jamaica.

12. “Three Little Birds” (1977)

An overt pop move, one so sweet it’s almost sugary, “Three Little Birds” is soothing in its gentle sway, The track features a sing-song melody countered by washes of keyboards as breezy as steel drums. It’s little wonder that the Bob Marley estate has acknowledged the song’s warmth by giving it a family-friendly animated video years after his death: it almost feels like an uptempo lullaby.

11. “Stir It Up” (1967/1973)

Laying the groundwork for “Guava Jelly,” the 1967 single “Stir It Up” has a rocksteady foundation and romantic disposition—a combination exploited by Johnny Nash, who covered the song in 1972, bringing it to American and British audiences alike. Nash’s hit helped introduce Marley to an international audience, leading the Wailers to cut the song again for Catch A Fire, their 1973 reggae masterwork.

10. “Waiting In Vain” (1977)

Many of Bob Marley’s love songs of the early 1970s had a distinctly carnal undercurrent, but by the time he wrote and recorded “Waiting in Vain” in 1977, he abandoned the outright sexuality. The song is a plaintive plea, an outpouring of doubt and emotion that feels tender and vulnerable—a notable softening of the rough outsider image Marley created during the prime of the Wailers.

9. “One Love/People Get Ready” (1965/1977)

Bob Marley first released “One Love” way back in 1965, when he—like the rest of Jamaica—was immersed in the sway of ska. He returned to it several times over the years, but when Marley paired it with a cover of Curtis Mayfield’s “People Get Ready” for 1977’s Exodus, he cut the definitive rendition of the tune: an ode to peace, love, and harmony whose sunniness belies the ache at the song’s heart.

8. “Burnin’ And Lootin’” (1973)

Among Bob Marley’s protest songs, “Burnin’ and Lootin’” is the angriest: a track that captures the desperation that’s the kindling of revolution. Marley paints the broad strokes of oppression—waking under a curfew, faces dressed in “uniforms of brutality”—but focuses on the human needs that, when denied, lead to an uprising. The Wailers don’t offer catharsis here. Instead, they operate on a slow boil, suggesting the steady simmer that leads to an explosion.

7. “Buffalo Soldier” (1978/1983)

A posthumous release—Marley cut the original version of the song in 1978 and it was finished after his death for release on Confrontation in 1983—“Buffalo Soldier” takes its inspiration from the Black soldiers who fought in the Civil War, then were sent to battle Native Americans in the American West afterward. Outraged by two oppressed factions set against each other, Marley created a righteous song driven by an incongruously frothy melody—a seeming contradiction, yet the nagging chorus helps give “Buffalo Soldier” an indelible hook.

6. “Is This Love” (1978)

The first flowering of Bob Marley’s pop instincts, “Is This Love” eschews earthiness for ebullience. All bright beats and sunny melody, the song sounds like the onset of romance—a fleeting feeling given permanence in this buoyant tune.

5. “Could You Be Loved” (1980)

A deliberate embrace of disco, “Could You Be Loved?” furthered the pop overtures of “Is This Love” and, in some ways, bettered its predecessor. The key to the song’s success is how the tense, insistent rhythm guitar complements the washes of harmonies from the backing singers the I-Threes, and the big, relentless beat.

4. “No Woman, No Cry” (1974)

Possibly Bob Marley’s richest song, “No Woman No Cry” occupies the precise place where longing and comfort intersect. Through sketched memories, Marley creates a portrait of a bustling Trenchtown, the warmth of his experience colored by the bittersweet pang of nostalgia. Fitting for a song about community, “No Woman, No Cry” received its definitive reading in concert: the rendition on 1975’s Live! thrived on the interaction between the Wailers and the audience.

3. “I Shot The Sheriff” (1973)

Released just a year after the original version, Eric Clapton’s cover of “I Shot The Sheriff” ushered Bob Marley & the Wailers into the rock world and, along with it, the public at large. As popular as Clapton’s version was—and it did reach No. 1 on the Billboard chart—it couldn’t supplant the original, not when it so clearly crystalized the outlaw mythos lying at the heart of Marley in the early 1970s thanks to the Wailers’ languid, funky rhythms; they sounded like they didn’t care they were breaking the law.

2. “Get Up, Stand Up” (1973)

Written alongside Wailer Peter Tosh, “Get Up, Stand Up” is Bob Marley’s definitive protest song, a rallying cry in support of human rights. Inspired by a voyage to Haiti by Marley, the song urges the poor and the downtrodden to unite as one, to stand up for basic human dignity. Delivered with grit and urgency by the Wailers, “Get Up, Stand Up” is a universal anthem that retains its power in the hands of other performers, whether it’s a local band, Public Enemy, or Bruce Springsteen.

1. “Redemption Song” (1980)

Bob Marley spent over a year crafting “Redemption Song,” the final song on the final album he released during his lifetime. The prolonged labor isn’t evident within the tune itself, even though it carries precisely crafted allusions, specifically to the work of Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey. In Marley’s hands, supported by no more than an acoustic guitar, “Redemption Song” serves as an elegiac summation of his art and life, a testament to how he sought deliverance within the music he made.