Bluegrass Lost Two Pioneers in Mere Days: Why Bobby Osborne and Jesse McReynolds Matter

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

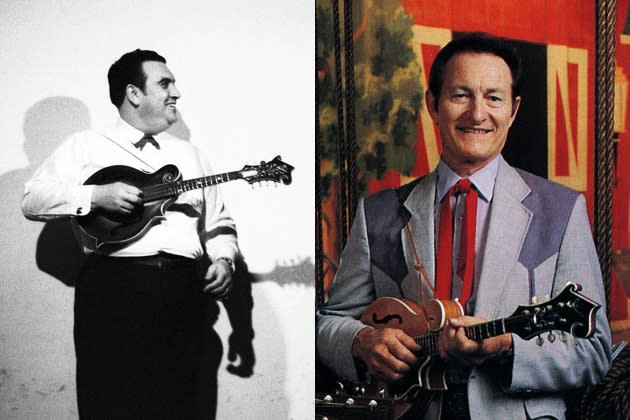

In the span of less than a week, the bluegrass community was rocked to its core: Jesse McReynolds and Bobby Osborne, two pioneering voices and musicians of the “high, lonesome sound,” died within mere days of each other.

McReynolds died June 23 at 93, while four days later, Osborne died at 91 on June 27. Both were renowned mandolin players and singers, whose melodic innovation and artistic integrity within bluegrass has echoed throughout the genre since its inception in the mid-20th century.

More from Rolling Stone

Taylor Swift Delivers Surprise Songs 'Evermore' and 'I'm Only Me When I'm With You' in Cincinnati

SAG-AFTRA to Extend Negotiations With Studios, Avoiding Strike for Now

Trump Threatens to Appoint 'Maybe Even Nine' Supreme Court Justices if Elected

“I just can’t remember a time in my life without hearing them,” says Ronnie McCoury, Grammy-winning mandolinist-singer for the Del McCoury Band and Travelin’ McCourys. “I’ve always thought that bluegrass mandolin came from three guys: Bill Monroe, Jesse McReynolds and Bobby Osborne — those are the three styles to me.”

Osborne fronted the Osborne Brothers with his sibling, Sonny (who died in 2021), while McReynolds teamed up with his brother, Jim (who died in 2002), to form the duo Jim & Jesse. In 1964, both the Osborne Brothers and Jim & Jesse were invited to join the Grand Ole Opry. Up until his death, McReynolds was the oldest living member of the Opry, followed by Buck White of the Whites at 92, and then Osborne.

“Bobby was the guy that took [bluegrass] to where it never had been before,” C.J. Lewandowski, singer-mandolinist for the Po’ Ramblin’ Boys, says. “His voice and his mandolin playing was so unique. He was a tremendous mandolin player, but his voice was so good that his mandolin playing was overshadowed.”

At the time of Osborne’s death, Lewandowski was in the midst of recording an album with the bluegrass elder statesman. To be released on Turnberry Records, the yet-to-be-titled collaboration was “about three-quarters finished” according to Lewandowski. He says the project will eventually see the light of day.

“Bobby was not only a bluegrass legend, he was a country music icon,” Lewandowski says. “He was known all over the world — he was the definition of a Grand Ole Opry star.”

“[Jesse and Bobby] were incredibly gifted singers and musicians,” McCoury adds. “And that’s really hard to find in today’s music world, to [be] so talented all the way around like that. There’s a lot of great pickers and there’s a lot of great singers, but there’s not a lot of both.”

For McCoury, it was the intricate, hard-to-replicate cross-picking that he most admired about McReynolds’ mandolin playing.

“I would attempt to do some Jesse cross-picking, but it was so far out to me,” McCoury says. “I just could not play it, especially up to the speed like he did. He created his own style.”

When Bill Monroe & His Blue Grass Boys (which featured guitarist Lester Flatt and banjoist Earl Scruggs) took the stage at the Grand Ole Opry in December 1945, the whirlwind, frenzied reception by the audience and listenership ushered in the “Big Bang of Bluegrass” — a new sound had erupted across radio waves from coast to coast.

A seamless blend of old-time, folk, Delta blues, Dixieland jazz, and mountain music, bluegrass emerged from the influential sponge-like nature and endless musical curiosity of its creator, Monroe, known as “The Father of Bluegrass.”

In 1948, Flatt and Scruggs left Monroe to form their own self-titled duo. Other marquee pillars of the first generation of bluegrass included the Stanley Brothers, Mac Wiseman, Jimmy Martin, Reno & Smiley, and Jim & Jesse and the Osborne Brothers. Which is what makes the loss of McReynolds and Osborne so monumental.

Hailing from rural Southwestern Virginia, the McReynolds boys began performing together in the late 1940s, only to sign with Capitol Records in 1952. What resulted were several signature numbers throughout the years, including “Cotton Mill Man,” “Diesel on My Tail,” and “The Ballad of Thunder Road.”

Birthed from the desolate hollers of Southeastern Kentucky (and coming of age near Dayton, Ohio), the Osborne Brothers kicked things up a few notches, taking the traditional bluegrass of Monroe and pushing it across the once-forbidden musical boundaries into popular country music. Radio jingles like “Rocky Top” and “Ruby, Are You Mad” became staples of the respective genres. (In fact, Osborne first sang “Ruby, Are You Mad” on an Ohio radio station in 1948, and went on to become a member of the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers the following year.)

“Bobby was an electric guitar player first. But then he heard Ernest Tubb and those guys, and that’s what got him into [bluegrass and country music],” McCoury says. “And [Bobby] started putting that kind of [guitar] playing onto the mandolin. He was also a fiddle player, so was Jesse, and they adapted a lot of fiddle tunes and fiddle notes to the mandolin — more so than Bill Monroe.”

So, just what was it about Osborne’s mandolin style that set it apart?

“Bobby played almost every one of the melody fiddle notes. I guess you could call it single-note picking, as opposed to Bill Monroe, [who] used a lot of down strokes and a lot more powerful stuff,” McCoury says. “Early on, Bobby played those little solos and intros to songs that were really so different from anybody else at the time.”

At 56, McCoury himself has been a professional musician since he was asked to join his father’s band when he was just 14. But for Ronnie, it’s always been about acknowledging the trailblazing ways and means of those who came before him.

“A guy like me who came along so many years later, there were so many people ahead of me that were playing [bluegrass], and that’s who you have to learn from,” McCoury says. “But guys like Jesse and Bobby, they didn’t have many people to learn from, especially on the mandolin. They were adapting the music they heard to the mandolin — they knew they had to be different.”

The Osborne Brothers were different in another way too: they had crossover appeal from bluegrass to country. In 1971 they pulled off the rare feat of winning the CMA Award for Vocal Group of the Year, beating out the Statler Brothers.

Bobby Osborne and Jesse McReynolds were also military veterans of the Korean War in the early 1950s. While stationed in Korea, McReynolds joined up with Charlie Louvin of the Louvin Brothers, and the duo played for the troops under the moniker the Dusty Roads Boys. Osborne was awarded the distinguished Purple Heart for wounds sustained in combat.

Gazing toward the future of the “high, lonesome sound,” it’s hard to think of what the cultural and sonic landscape of bluegrass will look like moving forward without Bobby Osborne and Jesse McReynolds. With the first generation of pickers and singers gone, where to from here?

“There are now two fewer spots on the Grand Ole Opry for bluegrass music, and that worries me,” Lewandowski says. “Bobby has been [playing bluegrass music] for 75 years. And after all those years, he still loved playing bluegrass, it didn’t matter if it was for 10 people or 10,000. It was incredibly inspiring to me.”

In terms of the current patriarchs and torchbearers remaining — the “living bridges” between the first generation of bluegrass and where we stand today — names like Bobby Hicks (age 89) and Del McCoury (84) bubble up, with Peter Rowan (80) and David Grisman (78) not far behind in terms of legacy and longevity. To note, McCoury and Rowan still keep a rigorous touring and recording schedule.

“My hat’s off to Jesse and Bobby,” Lewandowski says. “They left a trail that we can only walk on. We can’t improve on it.”

“[Jesse and Bobby] were pioneers,” Ronnie McCoury says. “This is the end of that generation.”

Best of Rolling Stone