Blood, Sweat, and Blackmail: How an Iron Curtain Tour Ruined a Rock Giant

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Music and politics were always entwined for Steve Katz. As a teenager in the Sixties, he’d travel from his apolitical family’s home on Long Island to Greenwich Village, where he’d watch radical folkies like Tom Paxton, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Dave Van Ronk play. He grew especially close with Van Ronk, who taught Katz guitar — and took him to socialist party meetings.

So it was frustrating and difficult when, in 1970, the U.S. State Department announced that Blood, Sweat & Tears – the band Katz had co-founded in 1967 — would embark on a government-sponsored tour of three Soviet satellite states, Romania, Poland, and the former Yugoslavia. Richard Nixon was in the White House; the Vietnam War was raging; and all Katz could do was pack his bags, grit his teeth, and tell The New York Post, “I hope when we come back we’ll give more free concerts and raise money for the Panthers.”

More from Rolling Stone

Oliver Stone Advocates for Nuclear Energy to Curtail Climate Change in Doc Trailer

A Frank Talk With the Ex-Pornhub Employee in Netflix's 'Money Shot'

Blood, Sweat & Tears’ Iron Curtain tour remains one of the strangest (and worst) decisions in rock history. At the time, they were one of the biggest bands in the country: Their 1969 self-titled album spawned three hits (“Spinning Wheel,” “And When I Die,” and “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy”) and won Album of the Year at the Grammys, beating out the Beatles’ Abbey Road alongside classics by Johnny Cash, the 5th Dimension, and Crosby, Stills & Nash. But after touring the Eastern Bloc, their standing cratered, pilloried on the left for being government pawns, pilloried on the right for being peaceniks playing rock and roll for commies on the government’s dime. The band carried on for decades — its lineup a revolving door of top jazz and rock players — but their status never recovered.

So why’d they do it?

“We were blackmailed,” Katz tells Rolling Stone. “We had to do this, or we wouldn’t have had a lead singer.”

This is the story BS&T finally tells 50 years later in the new documentary, What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears? (premiering March 24 in New York City and Los Angeles). It includes the revelation that, according to the group, they were forced to do the tour or their frontman David Clayton-Thomas — a Canadian citizen with a petty criminal record as a teenager — would be deported. But the film, directed by John Scheinfeld, is also an archival marvel, offering a comprehensive look at the tour and its aftermath with newly-discovered and remastered concert audio, as well as 53 minutes of unreleased video intended for a contemporaneous documentary that wasn’t just scrapped, but buried under still-unexplained circumstances.

The film is a fascinating look at a little-known chapter of rock history, offering fresh insights and facts while also conjuring perennial questions about propaganda, power, and polarization. As Katz tells Rolling Stone, “It was a pretty amazing experience, to be behind the Iron Curtain, and change my mind a little bit about what it’s like to live in an authoritarian country … The audiences were so great that I said to myself, ‘Wow, we’re really doing something here. I mean, we’re really making people happy.’”

But a bad taste still lingers, he adds: “I resented what happened to us. I lost a lot of friends and we lost a lot of [our] audience. And we couldn’t say anything about it.”

THE IRON CURTAIN TOUR WAS part of the State Department’s long-running Cultural Presentations Program, which sent American musicians around the world in a classic display of soft power. Throughout the 1950s, America’s musical exports were classical and jazz, with luminaries like Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, and Dizzy Gillespie participating in tours. But rock and roll’s potential became inevitable in the Sixties, especially after the global youth movements of 1968.

“It became clear to the State Department that young people were moving politics forward, and it would be best to connect with them,” says Ohio State University professor Danielle Fosler-Lussier, who appears in What the Hell Happened and literally wrote the book on the Cultural Presentations Program. “And to reach young people, you have to send music that young people are interested in.”

Blood, Sweat & Tears were the first major rock band to go on such a tour. Discussions likely began in fall 1969, not long after the band played Woodstock. Larry Goldblatt, BS&T’s shrewd and shady new manager (who’d just gotten out of prison for passing bad checks) spearheaded the initiative. It’s unclear if Goldblatt or the State Department instigated the conversations; but it’s undeniable that Clayton-Thomas’ immigration status was precarious.

Hailing from Toronto, Clayton-Thomas regularly crossed the border for gigs. He eventually settled in New York City, but was deported in 1968: “I’d been there for almost a year, working clubs,” the 81-year-old says today. “Technically, I was there illegally; I didn’t have a visa. Somebody turned me in. They came to my apartment at four in the morning, which the police always do — they love that four-to-six a.m. crap — hauled my ass, and put me on a plane back to Canada.”

But he was back in the U.S. within months, recalled to NYC to audition for Blood, Sweat & Tears after the departure of co-founder Al Kooper. Amidst the band’s ensuing success, they secured a working visa for Clayton-Thomas, but it required regular renewal, and his adolescent criminal history loomed large. By fall 1969, deportation seemed imminent.

Though there’s no proof, BS&T drummer Bobby Colomby tells Rolling Stone it “felt like someone from the government was pissed off” at the band. Katz notwithstanding, they weren’t particularly political, but like other artists at that time, when they were asked about, say, Vietnam, they spoke their minds. “When you’re successful, they put mics under your chin,” Colomby says. “We were the last people you should be interviewing about anything other than music, but we would answer: ‘No, this sucks. This is horrible what’s going on Vietnam.’”

Clayton-Thomas adds, “I think it was a whole attitude that we were part of the anti-war movement. Remember, they had John Lennon followed by FBI agents and they revoked his visa, too.”

About a week before Blood, Sweat & Tears left for Europe, on June 12, 1970, the State Department hosted a reception. “I showed up in a cobra skin jacket and a T-shirt with a big peace sign on the front,” Clayton-Thomas recalls. “A couple State Department people pulled me aside and said, ‘The T-shirt’s gotta go.’ I said, ‘I’m sorry, that’s all I got!’ Can you imagine? The government is getting bent out of shape because I got a peace sign on my T-shirt.”

The artists who went on these state-sponsored tours were often to the left of the U.S. government, Fosler-Lussier notes. But they saw an opportunity to travel, meet new people, and maybe even “advance their own peaceful aims.” Especially for Black artists during the Civil Rights era, it could be a fraught arrangement, but it never stopped participants like Louis Armstrong or the contralto Marian Anderson from being forthright about American racism.

In fact, public dissent or disagreement was arguably advantageous for the U.S. government. Clayton-Thomas, for instance, told a Yugoslavian youth magazine, “When I went to Washington for a reception, prior to our departure, I stood before American journalists and said that I am not going to Yugoslavia to tell those people what a good and wonderful government we have. I am in opposition.”

To the State Department, you couldn’t manufacture a more exemplary display of good ol’ American free speech. “A musician spoke out against the government, and nothing bad happened to him,” Fosler-Lussier says. “He wasn’t shot; he wasn’t taken away in a police van in the middle of the night. That was very powerful when Eastern Europeans could not speak openly against their government. In some ways, the State Department always has the upper hand over the musicians.”

Indeed, in an official report, the U.S. ambassador to Yugoslavia, William Leonhart, seemed more peeved at the “lack of politeness and consideration” BS&T showed when trying to wrangle the band for official receptions (compared to Duke Ellington, who played two shows in a day-and-a-half, attended every event, signed autographs, and “kissed all pretty girls on both cheeks!,” according to the report).

Even negative or critical local coverage was spun as positive. An article in a Zagreb student paper, Omladinski Tjendik (translated for Leonhart’s report), laid into the state-sponsored tour: “All of us know that the American Government is not something special, that it is primarily cunning businessmen who do not do certain things for peanuts… Whatever Uncle Sam does, and especially Nixon’s version, is done with a goal and calculation.”

The embassy’s big takeaway? Only that the author was upset the show was under “State Department patronage.” And besides, the author still “quoted from our USIS press releases.”

Overall, BS&T’s concerts in Yugoslavia and Poland went well, but in Romania tensions were high. The oppression under authoritarian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu was palpable, the constant surveillance disconcertingly obvious. Katz remembers a meal in Bucharest, where a waiter came up to him and whispered: “Can you send me a Led Zeppelin album if I write down my address for you?”

In spite of, or maybe because of, all this, the two shows in Bucharest were a marvel. The crowd was electric and enthralled — but that enthusiasm clearly troubled Romanian authorities. After a crackdown at the first concert, BS&T were given a list of demands. They were told to play “more jazz” and music with “less rhythm,” and refrain from “suggestive body movements” and “throwing musical instruments” — the latter two likely referring to Clayton-Thomas’ on-stage antics, and specifically his bit of smashing a gong before the start of their cover of Traffic’s “Smiling Phases.”

Unsurprisingly, an embassy cable notes, “Clayton-Thomas gyrated just as much as the night before and threw even more instruments off the stage.”

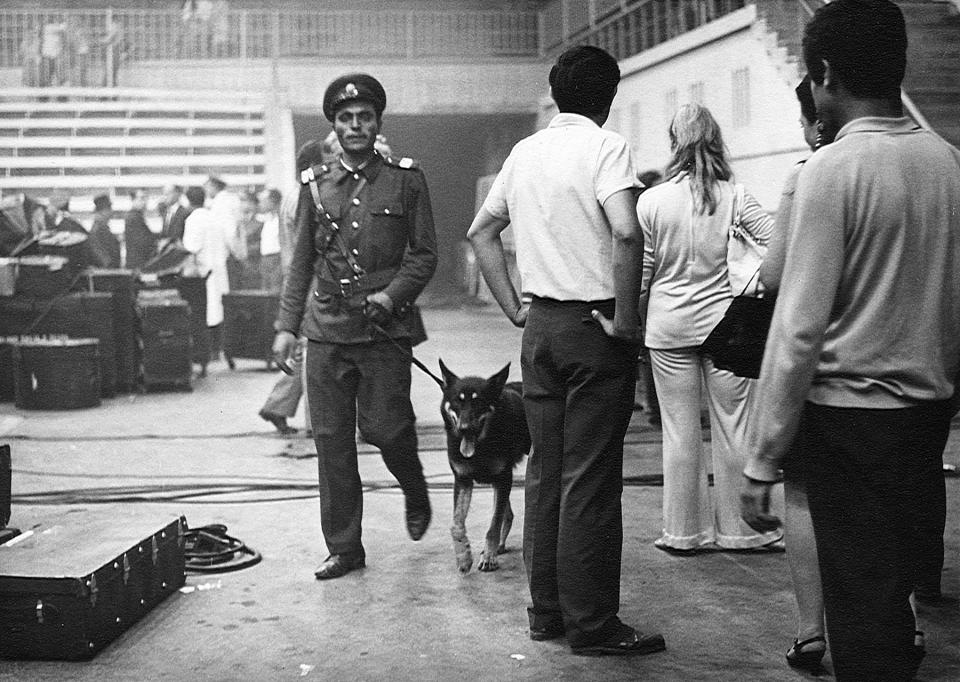

But the consequences were brutal. “All the doors slammed shut,” Clayton-Thomas remembers. “They weren’t trying to get the kids out of there. They were locking them in. Now that’s scary. And then the big doors at the end opened up, and 30, 40 dogs were set loose. A couple of hundred soldiers came in with billy clubs. They just attacked the audience — these are 15, 18 year-old kids! And I remember sitting in the dressing room with [bassist] Jim Fielder and we were both crying. We didn’t mean to do this; who knew this could happen?”

A final show — a charity concert for flood victims — was canceled and BS&T left Romania the next day. The documentary film crew from National General Television Productions had to concoct an outrageous scheme out of a James Bond film to sneak their footage out of the country before the authorities could confiscate or destroy it.

Still, the Romanian ambassador, Leonard Meeker, raved about the “all-too-successful tour of Romania,” how the “rapport between the band and the spectators (particularly the younger people) far exceeded the expectations of Romanian authorities,” and how “traditional Romanian decorum was shattered by these young people.” Of the violent efforts to clear the crowd, Meeker said only that these measures “were far from gentle.”

Ira Wolfert, a Reader’s Digest reporter who accompanied the band on the tour, said the quiet part a little louder in a phone call with Office of Cultural Presentations Director Mark Lewis: “[T]he Government of Romania was afraid that they would be blown out of power by saxophones, and I means [sic] this seriously. … They didn’t want more people being too joyful.”

GAUGING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF a Cultural Presentations Program tour was a complex, imprecise endeavor. Noting that the program relied on convincing Congress it was worth funding, Fosler-Lussier says the contents of official reports varied widely: Some focused on audience reactions, others on whether the right people were in the room. The latter could mean important local figures or members of the government, though by 1970, it was all about young people and intellectuals. In terms of reaction and crowd composition, the Blood, Sweat & Tears tour was a massive success: “The Embassy would urge most strongly that similar popular music groups be made available under the Cultural Presentations program in the future,” wrote Walter Stoessel, the U.S. ambassador to Poland.

But, as Fosler-Lussier tells Rolling Stone, “what was good for the State Department was not necessarily good for Blood, Sweat & Tears.”

On July 16, 1970, about a week after BS&T returned to the U.S., they flew to Los Angeles for a concert and were surprised at the airport by a press conference. Clayton-Thomas, Katz, and Colomby sat before 50-odd reporters, many of whom were eager to make the band account for themselves, their sins, and the sins of their government (and maybe even their music, depending on taste). The trio was bewildered, but tried to communicate what they’d seen.

“When we went there, as much as we couldn’t stand Nixon and the war, we saw communism in an even more repressive form than we see today, because these were satellites,” Colomby tells Rolling Stone. “We couldn’t help but say, ‘Yeah, it’s fucked up here, no doubt. But that — you do not want. It’s horrible.”

The underground, left-leaning press — which had helped build up BS&T, but begun backing off after they booked a bunch of shows in uncool Las Vegas — wanted none of it. Rolling Stone’s own David Felton attended the press conference and wrote a story — which he revisits and repents for in the film — that drips with disdain: “The tour resulted in several examples of Rumanian police brutality captured on film, a major riot during a concert in Bucharest, and the conversion to Americanism of at least nine persons — all members of Blood, Sweat & Tears.” The story’s ruthless kicker about the show the next night at the Hollywood Bowl? The “performance hardly caused a riot.”

Then, on July 25, Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies posted up outside BS&T’s concert at Madison Square Garden with fliers decrying “Blood, Sweat & Bullshit.” Inside, someone threw a bag of horse shit, which landed on Colomby’s drum kit (an event lovingly and dramatically reenacted in the doc).

The band got it from the right, too (kinda). William Scherle, a Republican congressman from Iowa, issued an official complaint about the tour’s cost, the band’s anti-war politics, and Clayton-Thomas’ Canadian citizenship. But really all that did was bring the tour to the attention of Henry Kissinger, who told Nixon that this rock and roll band had returned from behind the Iron Curtain with “more balanced perspectives about the United States.” Nixon was intrigued enough to ask how the administration might gin up more coverage.

The cumulative effect of all this, it seems, was a terminal, mainstream diagnosis: Blood, Sweat & Tears was not cool.

Over the next few years, the band’s popularity waned. Members started to leave and found new projects, with most members going on to enjoy long careers in music. (Even Blood, Sweat & Tears has been active in various forms since 1984, though no original members currently perform with them.) But the stink of the Iron Curtain tour still hung around. Katz, for instance, went on to work with Dave Van Ronk again, but said he always felt his old musical and political mentor “was a little cold after that.” Other friends ignored him, so he ignored them.

The Cultural Presentations Program didn’t fare much better either. Over the next few decades, Fosler-Lussier says, the program’s budget shrunk as the cost of the Vietnam War rose and the reach of American culture grew with the expansion of global media. Though the program, in its smaller size, continued to focus on reaching young people in the U.S.S.R. and Eastern Bloc countries, only one other major rock band participated: The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, which visited the Soviet Union in 1977.

Scheinfeld acknowledges there’s “some aspects of a Shakespearean tragedy about this whole thing.” It’s the story of a band ensnared in a vortex of polarization and indifferent geopolitical machinations, their fate resonating with something the spy novelist John le Carré once wrote: “There is no victory and no virtue in the Cold War, only a condition of human illness and a political misery.”

If there is one glaring good, it’s what Scheinfeld highlights in What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears: The experience and euphoria the band shared with the audiences in Yugoslavia, Romania, and Poland. The most powerful parts of the film are hearing from some of these concertgoers, whose memories remain vivid after more than 50 years.

Recalling some footage from the first concert in Bucharest, Scheinfeld adds, “The crowd starts to chant ‘USA, USA, USA,’ and I thought, ‘That’s part of the statement we’re making here.’ Yes, this horrible stuff happened to the band, but the impact they had on those young people is no more evident than in that chant — what it meant to them, and the fear that the government had over what that might bring about.”

But even a chant of “USA, USA” can feel unsettling, especially from a crowd about to be brutalized by the state. Is it possible to accept the United States of America, with its own long history of brutalizing its citizens, as a symbol of freedom just because we’re more permissive of rock and roll? Is it also possible to accept that a government engaged in so many awful things around the world during the Cold War, also deployed so much great music that reached audiences who were forever changed by it?

Some behind the Iron Curtain were also mulling the inherent, impossible tensions of cultural propaganda as they eagerly anticipated seeing Blood, Sweat & Tears in the summer of 1970. The one “negative” piece about the tour, printed in the Zagreb student paper, is not just a grumble about State Department patronage. It’s a considered essay on the problem of music as propaganda, the way a so-called “cultural exchange” doesn’t feel so much like an exchange, but U.S.-approved cultural aid with inescapable impositions — when all people want is to enjoy something wonderful.

“I do not ask whether we needed a concert of this kind of music and style or not,” the author writes. “My answer is YES. Yet, have we been run down so much that we have to accept the cultural aid — not exchange, the aid. Have we been run down so much as to take it because it is free (and yet it certainly is not free). … In the end, it bothers me because propaganda is so perfidious, cunning, because a musical event is turned into propaganda; I am bothered because we place ourselves in an inferior position.”

The archival material from the State Department’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs quoted in this story was graciously provided by the University of Arkansas Library’s Special Collections Department.

Best of Rolling Stone