Blake Mills Has Played Tasteful Guitar for Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan. He’s Ready to Shred

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

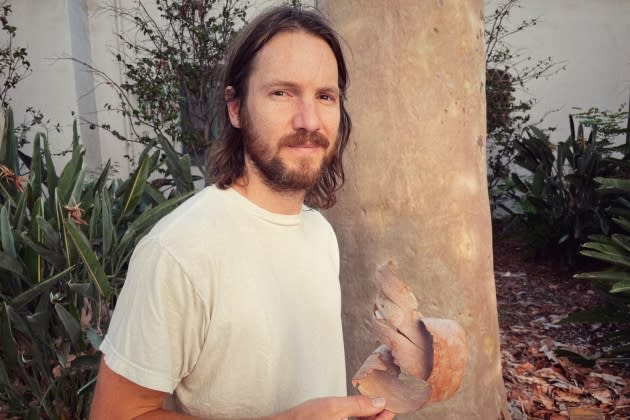

Blake Mills has the kind of CV, and accompanying reputation, that leaves little to quibble with. The 36-year-old Los Angeles musician is an ace producer (Perfume Genius, Feist, Marcus Mumford); an in-demand sideman and session player (Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, Phoebe Bridgers); and an exceptional singer-songwriter in his own right. But there’s one notion people have about him that Mills finds baffling: That “I’m this extremely capable guitarist who never allows himself to play.”

In other words, Mills doesn’t like to shred. Whether or not it’s accurate, it’s something Chris Weisman — Mills’ main collaborator on his new solo album Jelly Road (out July 14) — was keenly aware of. And something Weisman was eager to address.

More from Rolling Stone

Tangled Up in Blue Pencil: Bob Dylan Had Thoughts on 'A Complete Unknown'

Legendary Concert Promoter Ron Delsener Looks Back on 60 Years of Live Music Madness

Bob Dylan Continues His Grateful Dead Cover Streak By Breaking Out 'Stella Blue' in Spain

“Chris was like, ‘I get it’ — this idea of holding back,” Mills says of the Vermont musician, with whom he co-wrote and co-produced Jelly Road. “But he said, ‘I think on this record, you should try whatever the opposite of that is.’ He was a proponent of guitar solos, essentially. And I went with him on it.”

It took Mills a few songs to feel like he was “earning the space,” but it finally clicked when he let it rip on first single “Skeleton Is Walking,” specifically over the swooning, nylon-string stroll he and Weisman laid down as the song’s foundation.

“It was the first time where I felt like there was a real reason to have that instrumental voice on the album,” Mills recalls. “The solo was saying a lot of things the singer couldn’t. I was really grateful to Chris for putting that idea in the room.”

Mills — as his credits suggest — loves nothing more than collaborating. But on his four previous solo albums, he’s largely led the charge himself. While he’s welcomed help from other top-notch session players, songwriters, and studio technicians, Jelly Road is the first time Mills has had a co-producer or let himself be produced as an artist.

It was easy to trust Weisman, who has quietly constructed a vast musical world in Brattleboro, Vermont, where he was content to let his work spread naturally through those in the know. When Mills learned of Weisman’s massive oeuvre, he was immediately hooked. “I dove in headfirst, and swam as deep as I could,” he says. “It’s like picking up the Odyssey or something.”

Keen to work with Weisman, Mills reached out with an offer around 2019 for a project that he figured Weisman — given his own reputation — would likely decline: The soundtrack for Prime Video’s adaptation of Daisy Jones & the Six. But as it happened, a bit of Seventies rock & roll pastiche was exactly what Weisman was looking for.

Mills and Weisman spent the next several years working together remotely on the Daisy Jones soundtrack. Somewhere in the midst of all that — Mills can’t remember exactly when — they started writing the songs for Jelly Road, and in spring 2022, Weisman flew to L.A. to record. One of the first things they did after finally getting in the same room together was compose and record the bridge for a song called “There Is No Now.”

“It was a wonderful feeling where you not only land the trick, but it’s instantaneous,” Mills says. “All the instruments we used to write and compose it, immediately went on the record. It’s nice that the recording is forever a document of also the writing.”

Like all of Mills’ best work, Jelly Road is inventive and immersive, a deft blend of familiar folk, rock, country, and jazz patterns, but accented with far-out explorations. And thanks to Weisman, Mills believes the album is his most personal in years. “I feel like I’m more in touch with myself on this record than maybe I have been since I was in my early 20s and writing the first songs I ever sang,” he says.

The Daisy Jones soundtrack was a specific project, with a specific goal, and a lot of outside stakeholders. How do you think working under those conditions influenced your creative partnership with Chris?

In some ways writing on assignment — especially if it’s going to be performed by another entity — is kind of liberating. We still went through a long process of editing, tweaking, and trying to get it right. But as writers, we were more willing to allow certain things to live in the song and not second-guess them. There was more of the kind of acceptance you have when listening to somebody else’s record: You let them be themselves, you allow them to unfold in whatever way it’s about to hit you. It was a freeing and interesting way to start our friendship and our creative partnership.

After you released “Skeleton Is Walking,” you shared a guitar tutorial on Instagram and noted that you hear the song in B-flat, but Chris hears it in E-flat. What does that difference say about the two of you?

It says so much. That phenomenon kept happening over the course of making the record. On “Jelly Road,” we hear the chorus starting on different measures and different chords. I think the precious thing about that is to never work too hard to lose the perspective that each of us have. I don’t think there would be any benefit to trying to make Chris hear it from where I’m hearing it or, vice versa. The value is in the fact that you’ve got two people who are active in this conversation together, but they’re, at times, talking about two different things. But it’s still coherent. It’s almost comedic, especially if you’re the audience and you know that the two people are hearing it differently.

How did you and Chris handle writing lyrics on this album?

Some songs emanated from a Chris lyric and I found my place on the music side; and then there are instances where it’s the opposite. There was definitely a process of finding a balance between things that, musically and lyrically, felt more like Chris than me, while still knowing I was going to be the singer. Everything was written in a way that felt like I could do it without thinking too hard about it — that felt natural. But that said, Chris, as a lyricist, is so talented at writing simply, so when I’m singing lyrics that were written by him, I feel like an actor working with an incredible script. I’m able to access parts of myself because of the strength of the writing that I have not been able to access when I’m the sole writer.

Guitarist Wendy Melvoin, who played for Prince in the Revolution, appears on this album, and there’s even a song named after her. How did she come to be involved?

When I knew Chris was coming to L.A., one of the things I was excited about was he was gonna get to meet some musicians who, for him, are like gods. And at the top of his Mount Olympus is probably the era of Prince with Wendy and Lisa [Coleman] — he calls that “the Beatles of Prince.” Wendy is somebody I’ve known for years, and I just thought it’d be so nice if she came down, met Chris, and maybe played on some of the stuff we were doing.

She came in and the first few things that we played for her were “Unsingable” and “Skeleton Is Walking.” “Skeleton Is Walking” is famously — in my opinion — in B-flat, as is “Purple Rain.” And there was this voicing of a B-flat chord that Wendy plays on “Purple Rain” that Chris and I both love. We were hoping that she would do something along those lines. And when we mentioned it, she said, “What do you mean?” And we said, “You know, the ‘Purple Rain’ voicing,” and we showed her the chord.

She said, “That’s not how I play the chord!” So we were like, “Well, show us how.” She starts playing to [“Skeleton”] based on, I think, what her guitar part was in “Purple Rain.” As she was playing, we heard that spirit being imparted onto our song — it was the most chilling experience of goosebumps I’ve had in that room. It was magical.

You’ve gotten to be part of Joni Mitchell’s big musical return. What’s it been like working with her, prepping for these shows, and watching her play and sing again?

The first night I went to her house, we were told a bit about what the [rehearsal] jams were like. It’s usually a dozen people or so, everybody takes turns playing an original song or a cover; but for the most part, we’re up there playing Joni’s songs, just celebrating her. She’d listen, and sometimes she’d chime in and sing — she loves being around the music, and that’s kind of it. And the songs they’d usually do were the hits, the favorites.

So, I was up there with my friend Taylor Goldsmith [of Dawes], and we have our own favorite era of Joni, like Hejira, Night Ride Home, and Dog Eat Dog. And these records weren’t really represented in the jams yet. Coincidentally, that night was the first time that Joni had held a guitar, or tried to play a guitar. Kathy Bates was there, the actress, and she had gifted Joni this beautiful electric guitar. Joni sat with it for a second, and we sort of saw what things came to her first as a guitarist. She was barring these chords, but the guitar was not in one of her infamous open tunings. So I quickly put the guitar into a tuning based on what I could see her hands doing, which was open-D. And one of the songs that was very similar to what she started doing with her hands was “Come in from the Cold” [from Night Ride Home]. Taylor and I kicked into “Come in from the Cold” to see if any of it would come back to her — and she lit up. That was an incredible moment.

The other night, when we were at the Gorge, I was playing “Amelia” [from Hejira] with her and it felt like a continuation of something that happened that first night. It’s like a little side road alongside everything else. For me, just as a guitarist — all the songwriting aside — she’s such a powerful influence. I got to hold the master’s sword for a second. It was like being a video game [Laughs].

Do you know if she’s been writing any new material?

I don’t know. I think with anybody, it’s probably safe to assume there are unfinished things in drawers or scattered around the house. But on a day-to-day basis, there’s probably so much going on. One day, there might be a notion to try to pull some of those things up and finish them. And I think we’re all hoping. But the nice thing about what’s going on in Joni’s world is it doesn’t feel like it’s being led by things that other people are putting forward for her. It’s not like I get the impression that there’s pressure to get her into the studio. It would be precious if it were to happen, and if there’s a feeling toward it from Joni at any point, the support will be there. I basically keep one eye on my phone in case somebody calls and is like, “Hey are you around?” I’m always planning on being able to drop everything.

Is that similar to how you ended up working with Bob Dylan on Rough and Rowdy Ways?

That was different. Bob was looking for a studio, and he’s such a mercurial guy, I’m not sure what made him come to Sound City, which is the studio I’ve worked out of the last five years. He came into the room and immediately was like, “Yeah, this will work, this will be great.” And as he walked around, he was sort of noticing my equipment and instruments, and realizing that this was a little different than rolling up to a commercial studio, which is kind of a blank slate. He asked if I was going to be around for the next couple of weeks, or if I could be, and I said, “Yeah, absolutely.”

From that point on, I think the notion of what the record was grew day-to-day. His band was incredible and intuitive, and it was thrilling to see one of the greatest of all time go through the process that I’ve seen so many people go through, and have a similar experience. His attention to detail, and wanting to make sure he’s writing it as clearly as can be, and that he’s doing the song and the character in the song justice as a performer, was inspiring and educating. It was also fascinating because he’s just doing the same thing everybody else is trying to do in their own way. And you kind of go, “Well, of course!”

He’s an artist — with the same insecurities and the same indecision, oscillating between using “these” or “this,” crossing out a word and putting it back in. It makes it even more profound, more impressive, that these songs came from a human being.

Best of Rolling Stone