BlackBerry review: how a tech revolution became a geek tragedy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Technology delivers all types of incredible societal advances. But the mad-dash nature of Western capitalism and the emotional fitfulness of the consumer marketplace also creates graveyards of arriviste empires—faddish companies with a product or service that intersects heavily with a particular moment in time, but ends in the type of mismanaged disaster only fully understood postmortem. BlackBerry, directed by multi-hyphenate Matt Johnson, is an engaging new film that charts the incredible rise and spectacular flameout of its titular product, the world’s first smartphone—which, for a period of time, controlled 45 percent of the cell phone market and seemed unstoppable as a cultural force.

Spinning off Jacquie McNish and Sean Silcoff’s nonfiction book Losing The Signal, Johnson and co-screenwriter Matthew Miller invest heartily in the story’s personalities. But instead of reverence or preciousness, they frame BlackBerry as an oddball workplace dramedy about industry gate-crashers rudely ejected from a party of their own staging.

Read more

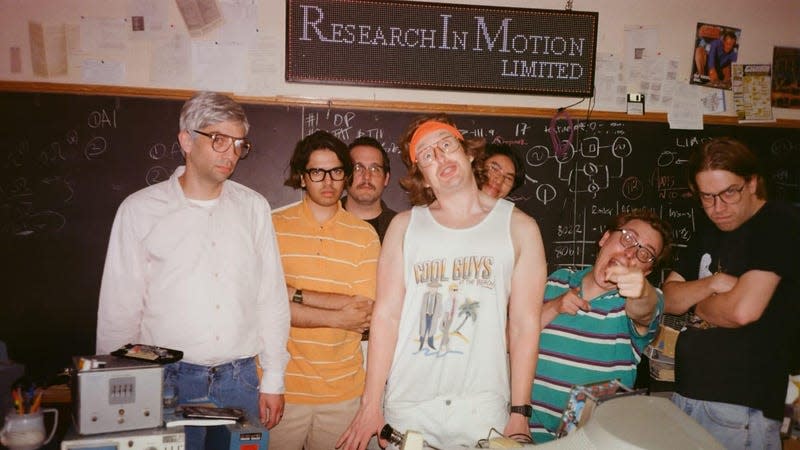

The film opens in 1996 in Ontario, where Mike Lazaridis (Jay Baruchel) oversees a software firm known as Research in Motion which operates like a social club as much as a business. Its culture of immaturity is embodied most robustly by headband-sporting co-founder Douglas Fregin (Johnson again), and the importance of collecting on money contractually owed seems on par with communal video game sessions.

Into this den of juvenilia steps Jim Balsillie (Glenn Howerton), who talks himself into a job as CEO. He quickly recognizes Lazaridis’ value as an inventor and fast-tracks an aggressive plan for a fanciful prototype that will leverage existing data networks and allow customers to quickly access email from their mobile devices. BlackBerry, the product, is a smash hit, and quickly becomes a market leader.

In an act seemingly designed to overtly terrorize his employees, Balsillie brings in as COO Charles Purdy (Michael Ironside), a scowling taskmaster who cancels movie night and derides workers as “little children playing with their little penises.” Balsillie’s strategic disengagement enables him to outmaneuver a takeover bid by Palm, Inc. CEO Carl Yankowski (Cary Elwes, in a small cameo that could stand to be fleshed out) and grow the company even more.

At around the 75-minute mark, the movie jumps forward to 2007, as Apple prepares the launch of its iPhone. While Lazaridis fiddles around with adjusted trackpads for the BlackBerry Bold, other dodgy deals and past corners cut come back to haunt the company, contributing to a fatal down swirl.

BlackBerry admirably shrinks the aperture of its story’s technical elements, and eschews the shrewd social inventorying or scrupulous myth-making that Aaron Sorkin brought to The Social Network and Steve Jobs. While the lack of a bigger look at the global mania the “Crackberry” wrought sometimes feels reductive, the characters here are interesting enough for the most part to acquit the tradeoff.

In broad strokes, the film is closer to something like The Founder, rooted in the shark-y sensibilities of an outside pathogen. It skews more humorous, though, seeking relatable bemusement over narrative tension. It’s not really a tale about business success and failure, but rather the loss of innocence, and the dividing line between adolescence and adulthood.

The other interesting aspect of the story is how, in many ways, Lazaridis and Balsillie represent two sides of the same coin. The former—an absorbed, head-in-the-clouds creative visionary—needed a ruthless, bottom-line-oriented fixer to unlock his full potential. The latter, meanwhile, needed something he could sell, even if he didn’t much understand all the details.

The acting wonderfully abets this interpretation. There’s a nervy, dangerous energy to Howerton’s mesmerizingly icy performance, which registers in an almost animalistic way. Rooted not so much in amorality as a complete lack of any guiding principle other than to always keep moving, Howerton portrays Balsillie as an apex predator who, even when on your “side,” could turn around and eat your face off. Constitutionally disgusted by the undisciplined nature of those surrounding him, Howerton conveys that Balsillie’s approach is less to bend people to his will than to simply operate at altitude, above them.

Baruchel, meanwhile, is afforded a nice chance to stretch. The first two-thirds or so of the movie finds him trading in tones and modes—scatterbrained, anxious, nervous apologia—that will read as familiar to many viewers. In its home stretch, though, as BlackBerry shows the weight of adult choices, Baruchel seeds his performance with small notes of both frustration and regret. It’s a smartly calibrated turn.

BlackBerry - Official Trailer ft. Jay Baruchel & Glenn Howerton | HD | IFC Films

On a technical level, Johnson oversees a smart package. A selection of songs by the Stereo MCs, Joy Division, Moby, and The Strokes taps into a general spirit of the changing times without relying on jukebox emotionality. Obviously modestly budgeted, BlackBerry embraces a low-fi vibe that suits it well, especially during the early, DIY days of the company. Cinematographer Jared Raab’s camerawork leans heavily into handheld and slightly voyeuristic, courting an aggressively inquisitive tone, and communicating the silent paradox gripping many of its subjects: we’re succeeding—wildly, actually—but is this in fact sustainable?

Eventually, though, this visual tack reaches a point of diminishing returns. The filmmakers feel so all-in and beholden to this approach that, for example, they cut away from Lazaridis during a pivotal emotional revelation to indulge more over-the-shoulder background detail.

It’s true that an operatic presentation of ruination or consequences wouldn’t fit BlackBerry. But it does feel like the movie misses the chance for some stick-the-landing moments related to the fates of its chief characters. That said, Johnson’s entertaining time capsule does still capture, in its unfussy way, one immutable truth: good times aren’t meant to last forever.

(BlackBerry arrives in theaters on May 12, 2023)

More from The A.V. Club

Sign up for The A.V. Club's Newsletter. For the latest news, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.