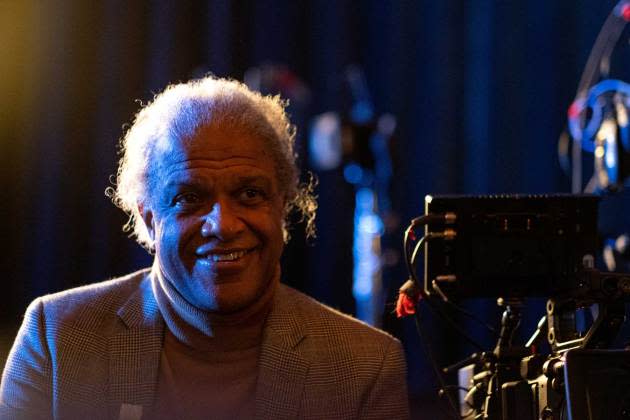

‘Is that Black Enough for You?!?’ Elvis Mitchell’s History of Black Cinema Is a Tour de Force

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Elvis Mitchell’s new Netflix documentary Is That Black Enough You?!? is a whirling exploration of a specific slice of Black movie history. Its main point of interest is the 1970s and its borders. The moment of Blaxploitation, Melvin Van Peebles, liberation politics, Pam Grier, Ali/Frazier, Lady Sings the Blues, and on and on. Mitchell, a longtime film critic, formerly of the New York Times and elsewhere, is not merely sifting through this history for history’s sake, even as the broad backbone of this film is a year-by-year accounting of the decade. This tour feels personal. It glitters with one-off observations and detours: into the careers highs and lows of figures like Harry Belafonte and Pam Grier, the deliberately numerous ties between the Black film industry and Black music, by way of titans like Isaac Hayes and Earth, Wind & Fire; into Black horror and comedy, Black style, Hollywood executives’ interest (or not) in catering to Black audiences, and the numerous forgotten bits of film history (remember when Warren Beatty’s Heaven Can Wait was originally meant to be helmed by Francis Ford Coppola, starring Bill Cosby?). Mitchell has an inside-scoop aptitude for titillating details and unexpectedly insightful connections, a gift for association and cool, collected storytelling that propels the documentary along at a fast, satisfying clip, overwhelming us the number of nods to stars, to movies — big and small — and to his own impressions.

But Is That Black Enough For You?!? is only two hours long, and the history being mined here is — as the documentary itself argues — vast. A not-totally-unfair complaint is that it all rushes by too fast, that it doesn’t dwell enough, isn’t neat enough of a history. Which, in a way, is the point. You may think you know this history, and many people do, because they lived it. They remember the intense emotionalism of Sounder (1972), and arguing over Coonskin (1975) and Mandingo (1975) and The Great White Hope (1970), buying the soundtracks for Superfly and Shaft, falling in love with Billy Dee Williams and Diana Ross in Mahogany (1975) and Diahann Carroll and James Earl Jones in Claudine (1974). Mitchell’s documentary — which is, itself, as much an act of remembering as it is a flex of the director’s own skillful film criticism — is as much for those people as it is for anyone, particularly among modern Black audiences, who’s never heard of Cornbread, Earl and Me (1975). At minimum, the movie gives you a heaping list of movies to add to your watchlist, with context as to why they stand out and why, for Mitchell, they’re so intimately braided into the larger picture of Black entertainment history. But this is at a minimum. Mitchell is aiming for more.

The movie’s title comes from the 1970 classic Cotton Comes to Harlem — a relevant choice on multiple fronts, being the work of an essential Black activist and independent director (Ossie Davis), sitting firmly toward the start of what would eventually be labeled “Blaxploitation” (it was adapted from a Chester Himes novel of the same name),with head-turning box office receipts that a Hollywood still led by white executives would start, for good and ill, to find compelling. This, in many ways, is the story that Mitchell is keen to tell: One of an industry in which pioneering Black artists were trying to scrape their way out of an old system with outdated ways of representing blackness, toward new representations and, with them, new questions and problems. Mitchell is unabashed in his affection and respect for Black genius. Look at his asides on, say, Melvin Van Peebles. Exploration of The Watermelon Man (1970) allows for an appreciation of its extraordinarily talented star, Godfrey Cambridge, and the work of Black satire. Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) lends itself to the means and importance of Van Peeble’s ballsy, strategic adaptation of the X rating; his way-ahead-of-the-curve deployment of a soundtrack album (early work courtesy of Earth, Wind & Fire), with its long and crucial afterlife in the Black seventies broadly speaking — to say nothing of Mitchell’s appreciation for the style and substance of what Van Peebles pulls off.

Mitchell does quite a bit of this. In the midst of burrowing into Black cinema history year by year, he takes time to single out an array of heroes — not only well-known names like Van Peebles or the biggest stars, but figures like director-artist extraordinaire Bill Gun (Ganja & Hess) and Suzanne de Passe (co-write of Lady Sings the Blues). There’s a loving tangent on the great, under-heralded actor Rupert Crosse — the first Black actor to get a supporting actor nomination — from his time at the Actors Studio, to his friendship with Steve McQueen, to his untimely death of lung cancer. The acting chops of a star like Pam Grier gets studied for its sensitivity, and with it, the sensitivity of roles for Black women in Blaxploitation fare. All of this, even as Mitchell is careful to complicate this narrative with murkier context, reminding us of the role that white directors and studios played in Blaxploitation, of the cinematic failures of titanic white directors who approached Black subjects misguidedly (The Liberation of L.B. Jones, for example, or more surprisingly, The Wiz), the role that money plays in all of this — and, not least of all, the strange ebb and flow of it all, the ways in which Black prominence in the entertainment industry is sometimes “in,” sometimes out, according to patterns that feel whimsical but aren’t. The patterns can largely be traced because they repeat themselves.

Sometimes the gaps in prominence are large enough that we forget — we’re encouraged to forget — what came before. It’s the habit of current discourse to claim, ad nauseam, that we — underrepresented groups — are seeing ourselves in movies “for the first time.” Mitchell’s documentary reminds us, intentionally or not, that the reality is far more complicated than this. Interviews with Samuel L. Jackson, Laurence Fishburne, Whoopi Goldberg, Zendaya, Charles Burnett, and many others are studded with intergenerational accounts of lives in the movies — both as movie-makers and, in the very beginning of their lives, devoted audiences. When we’re reminded of movies like Abar, The First Black Superman (1977) , or hear Mitchell and others reclaim their experiences of watching movies in majority-Black audiences in the ‘70s, it encourages the remembering of that longer history. Even Mitchell’s grandmother, he tells us, has movie memories — although hers are decidedly more troubled memories.

Mitchell is not merely giving a precis of an era in Black entertainment and film history — though Is That Black Enough?!? certainly satisfies on that front. He’s making a case for the sphere of Black film, for the specific sphere of Black independent film, as a site of great innovation, practically a laboratory for forms of Black cinematic expression that had not yet graced movie screens, and which, proving profitable and appealing to the public at large, would go on to influence moviemaking far beyond the work aimed at Black audiences. Always, he makes sure to situate his observations about Black cinema in context, reminding us of the concurrent strands in the white mainstream, be they the white antiheroes of the ‘70s — played by your Brandos, your McQueens, your Hackmans and Pacinos — or the Tarantino jive-talkers of the ‘90s, who, as Mitchell points out, spat lines that felt like they were written for Black characters.

Mitchell is smart. It’s pleasurable to be along for this tour of his mind and its nimbly kinetic knack for association and sharp inference. Even if you know this territory in the broad strokes, watching someone sort through it in their own way is invigorating on its own terms. The format of the documentary, with its mimicry of straightforward history, almost gets in the project’s way, because it risks setting viewers up to expect something closer to a robust history lesson than what this winds up being. I’ve heard complaints that the movie was too rushed, too short. And Mitchell’s charisma is to blame for this, too: you may wind up wanting that history lesson — from Mitchell, specifically.

More from Rolling Stone

This makes it urgent to remember where this movie starts. It starts in Mitchell’s mind — in his memory. With observations about a grandmother who said that movies changed the way she dreamed. And memories of being a young moviegoer himself, in Detroit. “Way more often than should happen,” he tells us early on, “films regarded as classics had a way of letting Black people down.” Cue: blackface images from Alfred Hitchcock and Singin’ in the Rain. Orson Welles and Laurence Olivier charring their faces to play Shakespeare’s tragic moor Othello. Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny, with their white gloves and expressions that, for Black audiences in the early 20th century, played a little differently than they do now. What’s useful about Mitchell’s documentary isn’t just the breadth of its history, the new names, the new movies that many viewers are sure to learn. It’s its firm situation in what this means to a Black audience, specifically, to the Black psyche of the present day and the past. Mitchell isn’t just giving us a tour of this history, he’s reclaiming it as his — and reminding us why he fell in love with movies in the first place.

Best of Rolling Stone