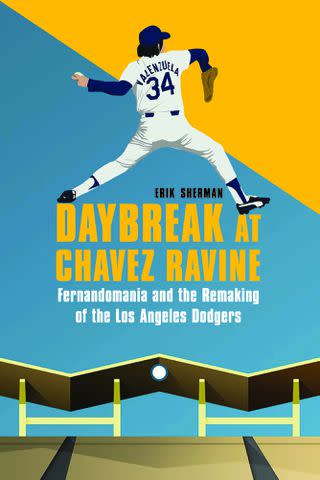

New Biography Revisits 'Fernandomania,' When Dodgers Rookie Inspired Mexican-American Community in L.A.

Fernando Valenzuela is the subject of Erik Sherman's biography, 'Daybreak at Chavez Ravine'

He wasn’t even supposed to pitch on Opening Day, 1981, but his team’s scheduled starting pitcher had a last-minute injury.

Then, Fernando Valenzuela, a 20-year-old rookie from Mexico, took the opportunity and ran with it, throwing a shutout in a Los Angeles Dodgers win against the Houston Astros. He kept pitching and remained unhittable, starting off the season 8-0, with five shutouts and an ERA of 0.50. He'd win the Cy Young Award, the Rookie of the Year, and the Dodgers would win the World Series.

He became a full-blown phenomenon: The press called it “Fernandomania,” and its significance extended way beyond baseball. Valenzuela became the first Mexican-American superstar in a city with a huge Mexican-American population. Yet it was a community that was marginalized.

There was also a painful history to consider. To make way for Dodger Stadium, city leaders in Los Angeles had brutally displaced a thriving Mexican-American community. For decades, tension lingered between the team and a huge portion of its potential fan base.

A new biography of Valenzuela — Daybreak at Chavez Ravine: Fernandomania and the Remaking of the Los Angeles Dodgers, by veteran baseball writer Erik Sherman — examines Valenzuela’s life and impact. In an email interview with PEOPLE, Sherman answered questions on his book.

PEOPLE: Why is Fernando Valenzuela such an important figure in baseball history?

Erik Sherman: Before Fernando, roughly only 5% of the fans at Dodger Stadium and at ballparks around the country were Mexican-American. After Fernando’s arrival on the scene, that figure shot up to 50% in L.A., and also substantially higher at stadiums across the country when he pitched. Dodger Stadium became like a Mexican festival, a dynamic that still exists there today. Go to a Dodgers game and you will see more Valenzuela jerseys than any other current Dodger — mostly worn by young people that never saw him pitch.

University of Nebraska Press

A strong case can be made that Valenzuela created more Dodger fans — worldwide — than any player in the history of the game—and that includes Babe Ruth and Jackie Robinson. He is on the Mount Rushmore of players that have impacted the game the most. He brought Mexican-Americans, long marginalized and in the shadows, out under the bright lights of the ballpark stands throughout America. He opened the gates not just for Mexican players to be scouted by big league scouts, but also the Hideo Nomos of Japan, the Chan Ho Parks of Korea, and, of course, the surge in Dominican players we see today, as well. He changed forever the face of the game both in the stands and on the field.

PEOPLE: How important is Fernando for the Mexican community, especially given the history of Dodger Stadium?

E.S.: The true, impactful story of Fernando Valenzuela didn’t begin in 1981 with Fernandomania; nor did it begin when he was born in 1960. Fernando’s story actually began a decade before his birth when the city of Los Angeles, through eminent domain, forced Mexican-Americans to leave their Chavez Ravine homes — most for below market value — to make way for affordable housing units. But the Red Scare put an end to the project in 1953, leaving the city stuck with 300 acres of land. Some families remained, having refused to sell. So when the affordable housing project failed, they thought they could stay. But when the city then sold the land to the Dodgers a few years later, some of those families were forcibly removed and then watched their homes get bulldozed before their very eyes.

Related: 'Stealing Home' : New Book Looks at Families Evicted when Dodger Stadium Was Built

It was an awful visual that captivated the country. The bitterness from the MexicanAmerican community over this would continue until the Dodgers, so eager to find a "Mexican Sandy Koufax," would start Fernando on Opening Day, 1981 — when all of their other starters were either injured or unavailable to pitch. That was the beginning of the greatest start to a pitcher’s career in the history of the game and the start of Fernandomania. Mexicans started coming to Dodger Stadium and, because of Fernando’s legacy, continue to stream to the ballpark today.

Focus on Sport/Getty

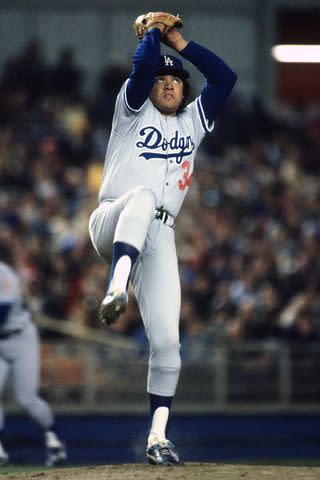

PEOPLE: You write beautifully about Fernando's everyman physique and unique pitching motion. How did his appearance on the mound make him a compelling character?

E.S.: Well, his appearance was so relatable to the Mexican community. I heard again and again from Chicanos that I interviewed how he reminded them of an older brother or an uncle. His everyman appearance was an endearing trait and proved to them that if someone with his physique and appearance — with a Mexican background — could become the best at his craft, then they could pursue their dreams, as well. And that wasn’t necessarily to become a baseball player. He inspired so many to go on to become professionals—teachers, doctors, lawyers, etc.

As for that eyes-to-the-sky delivery, no one will ever know how many millions of times it was imitated on little league, high school and wiffle ball fields!

PEOPLE: As a New Yorker, Fernandomania seems similar to "Linsanity," when Jeremy Lin briefly took the NBA by storm. What are the similarities and differences there?

courtesy of Erik Sherman

Erik ShermanE.S.: Fernandomania had far more reaching social implications and lasted the entire decade he pitched in L.A., whereas Linsanity was like a candle in the wind — very bright, but comparably speaking, very brief.

I think a better comparison would be the mania over Mark "The Bird" Fidrych back in 1976. But that only lasted a season or so. I don’t think we’ve ever seen a mania quite like Fernandomania. Remember, Valenzuela was an All-Star his first six seasons in the big leagues — the same number of appearances as Sandy Koufax.

PEOPLE: Why is now a good time for a Fernando Valenzuela biography?

Bettmann Archive

Fernando ValenzuelaE.S.: I thought the 40 year anniversary of Fernandomania — or roughly around that time — was a good start. But I really caught a huge break when the Dodgers decided to break with the tradition of only retiring Hall of Famers’ numbers and retire Fernando’s #34 later this summer. To help commemorate the event, Fernando is even on the cover of their yearbook this year — unheard of for a team with all the present-day stars they have.

There has never been a biography written about him until my book, so I am extremely proud to present to his fans the biography he so richly deserves. Fernando changed baseball, the Dodgers and the city of Los Angeles all for the better. I hope he reads it!

Daybreak at Chavez Ravine: Fernandomania and the Remaking of the Los Angeles Dodgers (U. Nebraska Press), by Erik Sherman, is available for purchase.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.