Biodynamic Wine Aligns You With the Energy of the Cosmos...Or So Its Makers Say

There is a certain type of tea (not the kind you drink) made from manure that was once stuffed inside a cow horn, buried on a farm for a season or two, dug up, and diluted with water. That tea is stirred in a bucket until a vortex, which absorbs the energy of the environment around it, forms. Every few minutes, the vortex’s direction is switched. After the mixture absorbs its share of environmental energy, it is sprayed, arbitrarily, over grape vines in a vineyard.

The spraying takes place according to a calendar that follows the phases of the moon and alignment of the stars to determine four types of days—root, leaf, flower, fruit—and the plants you should be cultivating on these days. It also dictates the types of wine you should be drinking on these days. Wines shine brightest on fruit days, although you can get away with a lighter white wine on flower days, too. If you’re drinking a Pinot Noir on a root day, you have made a huge mistake.

The label "biodynamic" is often attached to this intensive practice of winemaking, but it’s a type of farming in general—part practice, part philosophy. Biodynamics were first theorized a century ago by Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian philosopher and beekeeper who hosted a series of lectures in the 1920s decrying the creep of synthetic fertilizers and chemicals into farming. To this day, the biodynamic protocol refuses conventional additives, follows specific preparations for composting, and plans by that biodynamic calendar.

"We people tend to think we can control things," says Rex Farr, co-owner of Farrm Wine, a biodynamic vineyard on Long Island, New York. "But we can’t control anything. Biodynamic farming is about giving up control. It’s the PhD of organics. It includes energies that are not just in the soil but aboveground, too: how the moon affects the tides, how the stars and planets all play a part in the energy cycle that we here on terra firma are part of."

Biodynamic wines aren’t new, but as the reality of climate change sets in and younger generations look to spend money on brands paying attention to it, they have been newly attended to, whether wine drinkers understand them or not.

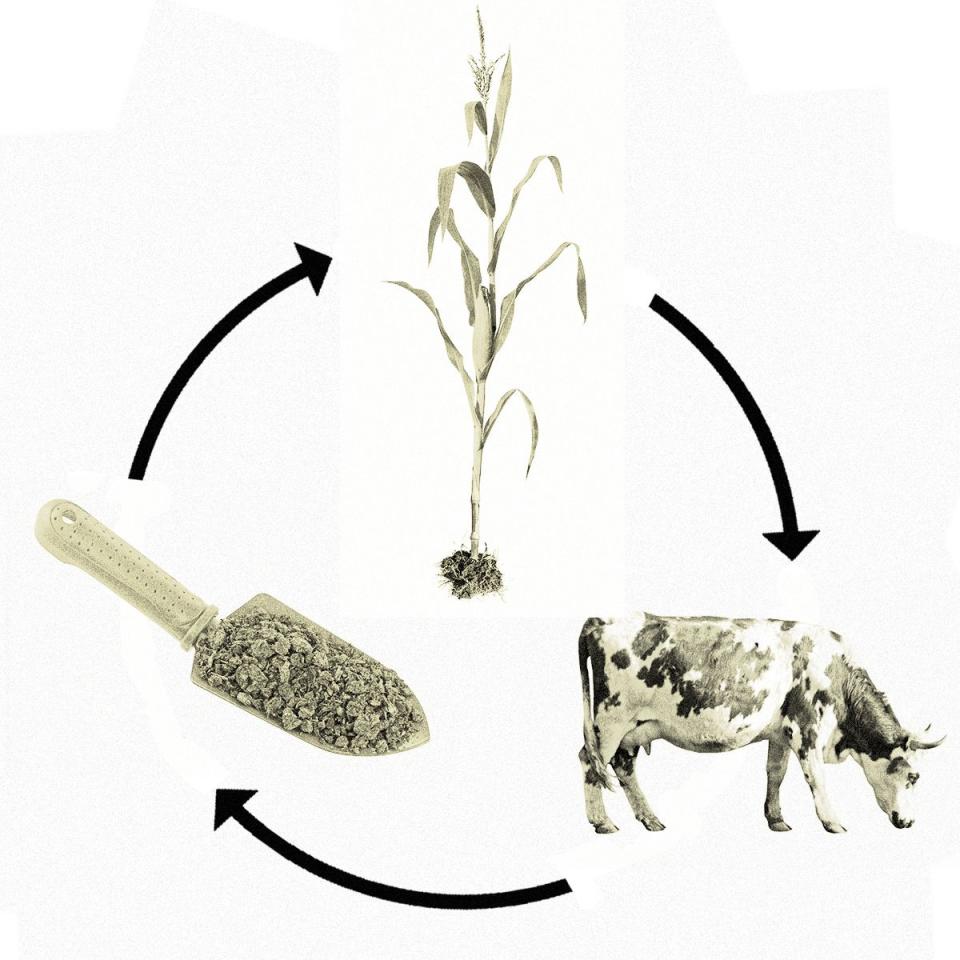

The big idea in biodynamics is self-sustaining agriculture: The biodynamic farm is symbiotic with its plants, soil, animals, and process. It does not take away from the earth, and it does little to disrupt the natural environment of the, albeit manmade, farm with human intervention and destruction. It predates the organic movement by about 15 years. But because biodynamic farming also follows the energy of the cosmos, an idea that has no basis in fact, the decision to drink biodynamic wine becomes a question not of taste or quality but one of integrity. It’s not about what kind of wine we like, but what our values are when we go to buy a bottle.

"A lot of consumers walk into the store and want a natural or biodynamic wine because they’ve heard the word around," says Jane Arbogast, assistant wine buyer at Eastside Cellars in New York City. "But when I push them, they usually don’t know exactly what it means. What they’re usually looking for is something with morals that match their own."

If you are seeking the biodynamic label, you’ll likely find it at your local wine store and definitely at the closest Whole Foods, in the non-conventional wine aisle full of other green-sounding words like natural, sustainable, and regenerative, nestled among low-intervention wines and dry-farmed wines. These seemingly eco-friendly words are not bound by any USDA (or even colloquial) definition and can easily misrepresent environmental responsibility to the wine-drinking masses. Natural might appeal to the psyche, but it has no real claim to health, despite the health food industry’s insistent usage. Natural is not inherently good. Arsenic is natural. It can also kill you.

"We call it 'greenwashing,'" says Ed Field, co-owner of Natural Merchants, an importer of organic and biodynamic wine for places like Whole Foods. "Natural, sustainable—those are like nails on a chalkboard. If you throw in terms that are undefined, it [all] becomes a marketing gimmick."

Part of the draw toward biodynamics is the sense that natural, sustainable, even organic, are not enough. "On a scale from the most green to the least green, biodynamic is the most extreme," says Arbogast. "It’s the most dedicated to preserving the earth's resources."

Biodynamic practices haven’t been updated since Steiner’s first call to them in 1924, and although any product with a biodynamic label is certified as such from an international governing body called Demeter, in the U.S., the USDA stamp of organic approval is the closest thing we have to a legally bound manifestation of the idea. But where organics focus on what we don’t add—chemicals, synthetics, and the like—biodynamics also emphasize not taking anything away.

"Say a plant is sick," says Farr. "The Western approach would be: Let’s go treat it with Roundup. We ask, 'Why is the plant sick?' I’m not just going to eliminate the problem but look at the source—the plant, the roots, the soil."

In this way, biodynamic winemaking sounds a lot like integrative medicine: If a person has a chronic skin rash, you don’t just prescribe a topical antibiotic and move along. You look at their stress levels, their food intake, their bloodwork. But biodynamics get real hippie, real quick. Some farmers believe in it like a religion. Steiner, for example, doesn’t just have modern-day students of the practice, but zealots. They live and breathe the idea that we as people and as an earth are all interconnected with the soil and stars, and we must limit the damage we do to the natural order of things. Wine is not just good or bad based on taste, but right or wrong, ethical or unethical.

That intangible, philosophical way of behaving might be what draws both farmers and wine drinkers to a century-old hypothesis. It’s a poetic ideal, which makes it impossible to study, impossible to quantify. If, ultimately, you want to know if biodynamic wine is quantifiably better than other green-sounding wines, you’re out of luck. Maybe that’s the point.

"Science compiles proof through controlled experiments," says Anna Katharine Mansfield, associate professor of enology at Cornell University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. "But biodynamics wouldn’t fit that frame. They believe you can’t replicate a system." You can’t test biodynamic wine in a lab, because it matters what day of the week and month and year you drink it on. It matters who you are with and how it is shared and why it is experienced at all. In Mansfield's opinion, if a farmer takes care of the overall, holistic health of a vineyard system, that's good. "But that also happens in organic growing. When you move to relying on the tides of the moon and all that, it probably isn't better than organic."

Viticulture and enology, the studies of winemaking, are built inside the scientific framework of falsifiability: We test ideas that have the capacity to be proven wrong. In this way, biodynamics seem more like religion than science. We can’t prove that the hypothesis is true, but we also can’t prove that it’s not true.

"I have no degree in agriculture, but I have 30 years of farming experience," says Farr. "We are just caretakers of what we do out here. We are not trying to control nature. There’s certainly more spirituality in biodynamics than organics. You can just feel something different. You really can."

Belief in holistic farming aside, some are driven to the biodynamic label by the perception that non-conventional wines are "healthier." It is probably more accurate to say that certain types of wine are less damaging or have fewer additives—that some wines are less bad than others.

"I have to laugh when people ask for wine without chemicals," says Mansfield. "Everything that makes wine taste good are chemicals. Wine is chemicals. Humans are chemicals. The most toxic thing in any bottle of wine is the alcohol. Let's just agree that we are ingesting a toxin because we like it."

For the record, a casual wine consumer cannot usually tell the difference between a biodynamic wine and other wines—natural, organic, and sometimes even straight-up conventional. Just tastes like good ole fermented grape juice. And no wine—not biodynamic, organic, nor natural—is a health food. But what you think, your perception of the wine, is really what ends up defining how good it is. If you think that the wine you bought is a moral investment, that you’re supporting sustainable farming, that you are a healthy person who buys healthy things, then you’ll probably have a better experience drinking that wine.

We have stories about wines because it has never been compelling to reduce the earth and our time on it into data in a lab. That’s why philosophies of farming and cosmic calendars and belief in something beyond what is here right now exist. Science can only arm us with so much.

Biodynamic wine is about those stories. Wine is not just wine. One thing is never, can never be, just one thing. Everything is connected. To some, it is impossible to separate wine from its former life as a grape, the grape from the tea-sprayed vine, or the tea on the vine from its energy in the vortex of space. The wine can't be stripped from its context, just as we can’t strip ourselves from the earth and our space in the stars, our morals from our wines.

You Might Also Like