Bill Mechanic On Movie Biz: Big Problems & A Few Suggestions On How To Fix Them

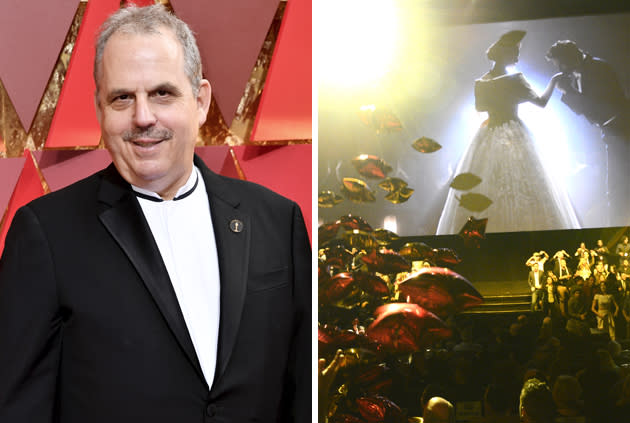

Editors Note: Bill Mechanic is chairman and CEO of Pandemonium Films and a former top executive at Paramount, Disney and chairman and CEO of Fox Filmed Entertainment when the studio generated Die Hard With A Vengeance, Independence Day and Titanic. He most recently produced Best Picture Oscar nominee Hacksaw Ridge. He was moved to weigh in after all the noise about windowing that came out of the just-wrapped CinemaCon.

The industry is in big trouble. Yes, that’s perhaps the only thing everyone can agree upon. Never has there been a more problematic time with a less certain future.

What isn’t unanimous are the reasons why. The prevailing sentiment is digital has changed the business—and the sky is falling. The movie business is being treated as an endangered species.

But those sentiments are virtually identical to those during the advent of television and then again when home entertainment (remember “HBO: The Monster that Bulldozed Hollywood” or “Home video will kill theatrical?”) burst on the scene. New technology, properly addressed, should not be a threat but an avenue of advantage. Assimilate change instead of seeing it either as a conqueror or destroyer. Never rush into its arms nor surrender to it. Size it up. Figure it out.

From the high point of moviegoing as a leisure-time activity in 1939, movies have done this. Absorbed radio, TV, cable, subscription TV, DVD, the Internet. It has absorbed all the competitive forms of entertainment with minimal drop-off. Growth in revenues comes from expansion of theatres (overseas), ticket prices, and absorption of releases in after markets.

Is the digital future different? Perhaps, but I’d argue not inherently and that if it is, it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. And that leads to what I believe is the biggest problem — in a word, leadership. That isn’t to say good people aren’t in positions of authority, but rather there is painfully little leadership in the movie business per se. The studio heads report into people that have no affinity for movies. As opposed to periods of change in the past, no one above the studio bosses have our specific industry solely in their purview. The studios, which essentially form the ecosystem of movies, have been swallowed lock, stock, and two smoking barrels by “pipes” (or, more correctly, by corporations whose main business is distribution). It’s not, “let’s figure out how we assimilate change;” it’s “how do we get it into our pipes quicker,” because we make our real money off the “pipes” not the content. Is it a surprise that Universal, owned by Comcast, or WB, soon to be owned by AT&T, are leading the way to the closing of windows with the least concern about impact on the movie business? (That was a rhetorical question). No, it’s not.

Who knows how the future turns out? (Another rhetorical question). No one. But what leadership means is thinking things through instead of just jumping on a popular bandwagon.

Who is speaking without a vested interest, be it NATO or the “Pipes?” No one. The only thing that has proven true over time is the movie business has assimilated change. Or at least until recently. I would argue that most of the negative impact has been caused by studios not thinking things through for the benefit of movies, not their owners’ other businesses.

What do I mean?

First, instead of understanding the nature of moviegoing, we have ignored it and based decisions on cash-flow desires. Sequential distribution has worked to the benefit of studios, even if it is a slow process (seven year cycles). Why? Because if a movie fails to recuperate in its first window, it has several other chances in other windows. While there are thousands of examples, Fight Club grossed only $35 million in its release but now has made tens of millions in video, etc.

But kids, we hear, want movies on their mobile devices, so theatres are endangered species. There are no studies to back that up. In fact, a recent worldwide study of filmgoing behavior shows that millennials, the age group most cited for mobile desires, has experienced only a 2% drop in filmgoing over the past decade. That is, the decade of mobile change. 2%. Essentially, no drop.

The millennials in the study instead cited moviegoing as a positive. When it’s something they want to see (hold this till later), millennials are social beasts who love to share their experiences. They don’t necessarily think theatres, as they exist, serve their needs, but that just means the theatres need to adjust. Mall locations are great, but some auditoriums ought to be set for interactions pre-or- post-screenings. Some auditoriums ought to allow cell phones, etc.

I believe that the so-called theatrical apocalypse is predicated on how digital impacted the music industry. And I would argue music is an inherently different experience than movies.

We listen in isolation, now more often than not on headphones, the ultimate in self-absorption. We listen more to songs than albums, (today there are no albums). The only social music experience is concert-going.

Movies are the opposite. Yes, you can watch alone, but that’s not the best way to experience movies, which aim to affect the audience emotionally—make people laugh, cry, be scared, and, at least once upon a time, think and discuss.

And how has the change been for the music business? To paraphrase a line from The Social Network, who wants to buy a music company stock? So why plunge headlong into a business system that isn’t in our advantage? The biggest reason cited is speed—maximizing marketing dollars in VOD (on PVOD). The universal truth here is consumers generally want what they want and they want that immediately. But when they really want it (eg, Beauty And The Beast) they go out and see it. They like to share the experience, millennials and families, the very audiences everyone seems to reference when saying change is coming. And moving up the window on what they don’t want is a fool’s errand. They won’t care if they get failed movies earlier. It’s practically the same issue as piracy. What gets pirated? A failed movie—no—you can’t give that away. The most pirated film in history is Avatar. Why? Because it’s the biggest film in history.

Experiments thus far with failed movies (eg. Pride, Prejudice & Zombies) mean nothing because they don’t replicate the environment they wish to promote. In the absence of everything being available in the same window at the same price, the results are meaningless. I experimented with windowing in home video years ago and things that haven’t changed are: 1) Everyone says they want things faster; and 2) Once a change in availability is standardized, they still want it quicker; and finally, 3) They only want what they want. The failed movies that appeared to jump in interest when they alone were available early, began gathering dust once other titles were made available. Watch the buy-rates of direct-to-VOD as more and more films go that route (oh yeah, those buy-rates aren’t available).

The gluttony of the studios has created the economic pressure of today. Over the last decade-plus, they have shot the industry in the foot by destroying the home video business.

While driven by the belief that movies, like music, are best collected via streaming, they did two things: 1) First, dumped a technology that didn’t create a meaningful audience (Blu-ray) on top of an existing technology (DVD), and thus confused the public who didn’t see the benefit of the Blu-ray over DVD, and 2) confused the pricing value (see what is going on with PVOD and VOD), and basically said: “don’t trust these people.” People may upgrade their phones each year but ask Apple what happened with iPad upgrades.

There are more issues in the mix. All I want to do is raise the thought that the future has not been determined and everyone ought to slow down for a moment to see what’s best for the movie business. The rush to VOD helped kill DVD/Blu-ray WITHOUT REPLACING the revenue. Moving up the window on VOD didn’t make enough of a difference. Those two facts ought to cause one to think more carefully about how to exploit VOD—it’s not whether to, but, how to.

And, though it’s less of a sexy discussion, why aren’t the leaders of the industry doing something within their power—making movies better. I cannot imagine sitting around in an executive position and simply watching the modern age of television (in streaming) come and steal the thunder away from movies. When television first broke on the scene, it caused a lot of hysteria about the future of movies but what it mostly did was prod movies to get better. To make them take better advantage of the media. To make them more adult. More responsive to teens. Marlon Brando and James Dean emerged as movie stars that spoke to a generation. The actors/characters doing that today are on some form of TV. What was the last truly great movie you saw? Hard to answer because there are so few. What was the last great TV show you saw? Hard to answer because there are so many.

Everything now in features is about marketing, not content. Pre-sold is the only standard of excellence. Why? Because pre-sold is a way through the market clutter. Two questions: 1) Don’t you think Netflix and Amazon, as well as all the cable outlets, are going to start looking for clutter-busters but offer greater creative freedom than the studios? 2) If sequels and pre-sold ideas are clutter-busters, why do the studios spend more and more money marketing these great ideas? The overspending on marketing is one more item not being addressed by the industry leaders, and it is their overspending that makes the mid-level picture less of a viable choice. Dial it back, people.

And yes, make better movies. Make The Godfather II, not Generic Movie Part 2. Sequels can be better but not when they are given a release date before they have a script.

Make movies for the audiences most likely to like them instead of everything being watered down to become a “four quadrant” movie. There’s Something About Mary wasn’t censored down to a PG-13 to gain audience. Bridesmaids wasn’t given a male hero-figure just to bring in the men. Deadpool did everything in its power to be the anti-movie comic book film. It dared everyone to bring their pre-teen kids to see it.

In Hollywood today we are a tale of two cities: In one sense we’re Detroit of the past—where it wasn’t about the car, it was about sales numbers. We’re good because we’re successful and who cares whether anyone likes the machine. Or it’s like Rio. The ultra-rich living in penthouses while the poor live in favelas with nothing in between. The middle class of movies have disappeared. You can make a $200 million tentpole without hesitation or raise money on an under $10M without a stutter step (as long as there’s a star in it), but try to make something not sequel-able, something of visual size or scope, that needs effects, and you could be banished to the same world I was with Hacksaw Ridge. Do you have the fortitude and stubbornness to wait 15 years to get your movie made? More to the point, should you?

Big is not inherently bad. Small is not inherently good. Good is good and bad is bad. Rules are guidelines but should always have someone questioning them. If theatrical movies disappear in the next decade or so, it would be self-fulfilling prophecy. The world will be a darker place and the culprit isn’t new technology, it’s the people who didn’t think things out.

Related stories

Oscar Buzz Begins With Studios Showing Off Awards Possibilities At CinemaCon

Stars Describe How They Lost It At The Movies As NATO Hands Out Achievement Awards - CinemaCon

Lionsgate CinemaCon Reel: 'American Assassin', 'Hitman's Bodyguard', 'Latin Lover' & More

Get more from Deadline.com: Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Newsletter