On Beyoncé's Renaissance : To be queer, gifted, and Black…oh what a lovely, precious dream

For me, and perhaps for a number of people like me, Beyoncé's latest album, Renaissance, is more than just a dance album (and a f---ing great one, at that). It's the history of dance music from the past 50 years, through the lens of the Black queer community, whom the singer uplifts to the level of iconography she has embodied throughout her career. A career built on the cultural tenets of that community.

Renaissance hit me where I live — at the intersection of disco and house music. I was too young, to my adolescent chagrin, to experience disco in full, platform-heeled bloom, but it was a mainstay in my home as a youth, at family barbecues and get-togethers. It was the sound of celebration, of the best of my love. There was something about that music, the joy and freedom in it, that spoke to my head, my heart, and my hips.

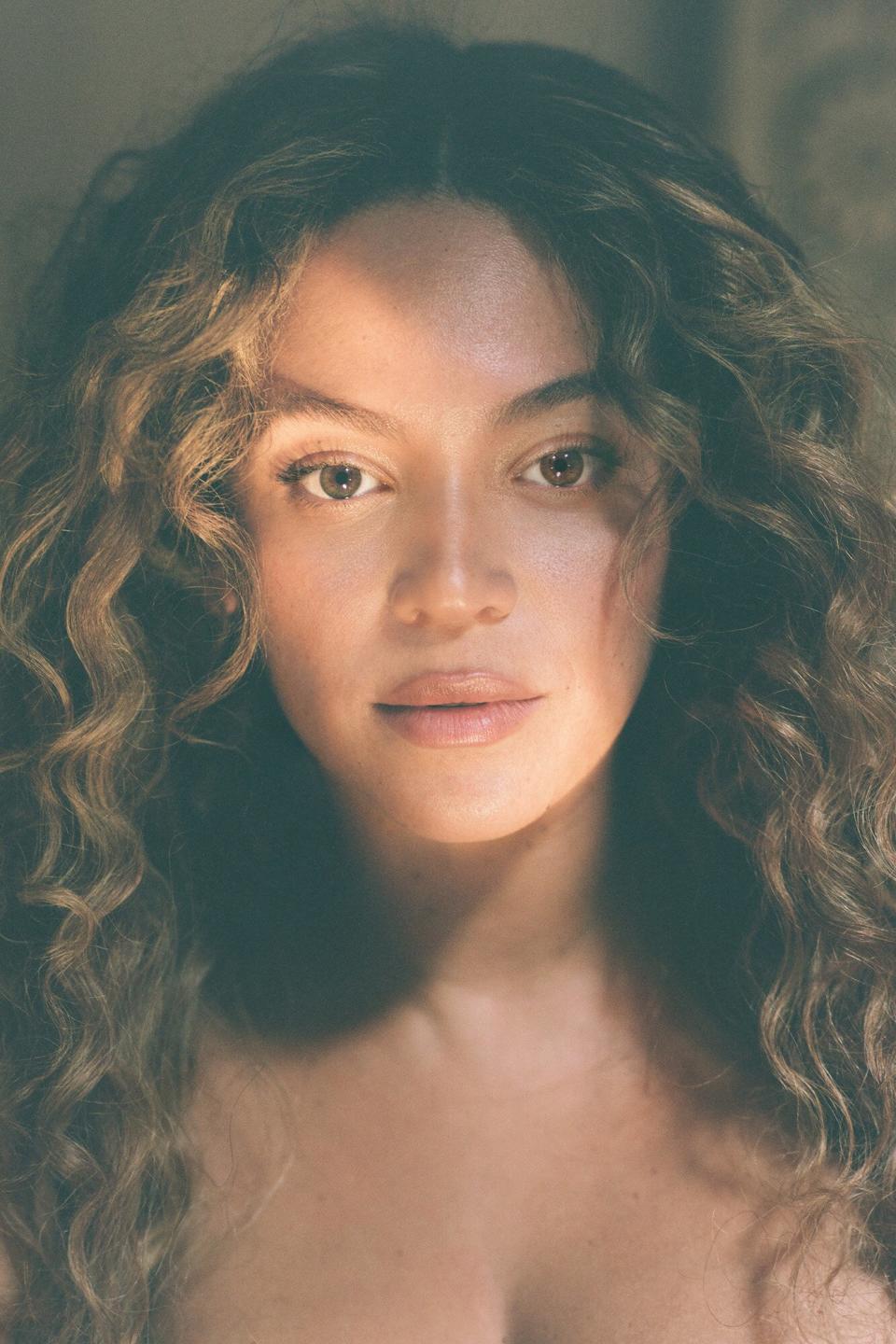

Carlijn Jacobs for Parkwood Entertainment Beyoncé dedicated 'Renaissance' to her gay uncle Johnny

I was lucky enough, however, to grow up in the '90s, when house music was ruling the airwaves, at least for the first half of the decade. Disco never died — it just threw on some bicycle shorts and implored everybody to dance now, only under the new guise of house. As disco faded in popularity, dance music went underground, where disco itself had started, and DJs like Chicago's Frankie Knuckles began experimenting with the funky foundations on which disco had boogied down, giving birth to house music.

In the '80s, the ballroom scene used disco tracks like Diana Ross' "Love Hangover" and Cheryl Lynn's "Got to Be Real" to live out the fantasy of the American Dream, to which they were denied access on the basis of their race, sexuality, and/or gender identity. Disco empowered the ball community, and as house music took shape, it, too, became the soundtrack to voguing. With the intervention of white artists like Malcolm McLaren, Madonna, and Jennie Livingston — whose 1990 documentary, Paris Is Burning, is the Rosetta stone of ball culture — voguing hit the mainstream.

Mason Poole for Parkwood Entertainment Beyoncé

Meanwhile, the community that birthed this phenomenon was decimated by AIDS, poverty, and violence. Mainstream attention waned, but the community vogued on. Decades later, shows like Pose and Legendary have reclaimed ballroom's legacy by centering Black and brown queer people both in front of and behind the camera. Into this slayed new world Renaissance (death-) dropped. (And before the gurls come for me, I know it's called a dip, but a pun's gonna pun.)

A friend said to me, "If Lemonade was the album that made the world realize Beyoncé was Black, Renaissance is the album that made the world realize Beyoncé is a…" — well, he used a word that could mean a cigarette, but in this case he was referring to a certified homosexual.

This album is ballroom. Beyoncé is in full drag, beat for the gods, walking the floor to her own propulsive beats one minute, calling the shots as emcee the next. She's both observer and innovator, melding disco, dancehall, deep house, Afrobeats, funk, gospel, new jack swing, techno, garage, synth-pop, and just about anything you can shake your ass to into one giant mission statement on the importance of Black queer creatives to what we think of as popular culture — i.e., Beyoncé herself.

Mason Poole Beyoncé

In its liner notes, Beyoncé dedicates Renaissance, at least in part, to her late Uncle Johnny, whom she refers to as her "godmother," the person who first exposed her to "the music and the culture that serve" as the album's inspiration. Beyoncé's "godmother" died from HIV-related complications when she was 17 — she would pay tribute to him at the GLAAD Awards in 2019. Upon Renaissance's release, Bey's mother, Tina Lawson, shared the photo her daughter uses in the liner notes on Instagram and the story behind it.

"Johnny was the closest human being in the world to me. We were inseparable growing up! Later, he was my nanny/housekeeper/designer/dance partner/confidante and bestie. I laughed constantly with him and trusted him unconditionally!" Lawson wrote. "When he died, a piece of me went with him. Solange and Beyoncé worshiped him. He helped me raise them. And influenced their sense of style and uniqueness! He made Beyoncé's prom dress."

On "Heated," Beyoncé, in full ballroom emcee mode, chants, "Unnnnncle Johnny made my dress / That cheap spandex / She looks a mess!" as a fan clacks in the background.

Certified. Homosexual.

To anyone who's been paying attention, it should come as no surprise that a gay man was instrumental in the formation of Beyoncé Giselle Knowles Carter. I mean, her high ponytail game, alone. But here she draws the line from the Black queer community to Beyoncé™ more explicitly and directly. Without Uncle Johnny, and the Uncle Johnnys of the world, there would be no Beyoncé.

With Renaissance, the superstar embodies ballroom — and by extension, Black queer influence — as a means to exalt it as the thing that is aspirational. Importantly, Bey also brings along Black and queer artists like Big Freedia, Honey Dijon, Ts Madison, and Syd to enhance and inform these lush soundscapes. Ballroom is, after all, a collective experience. But where the balls originally envisioned the American Dream — and therefore whiteness — as the aspiration, Beyoncé flips the script.

"I'm looking for motivation / I'm looking for a new foundation / And I'm on that new vibration / I'm building my own foundation" she declares on "Break My Soul."

Mason Poole Beyoncé

For me, and perhaps a number of people like me — the Uncle Johnnys, Black and brown trans folks, QPOCs, etc. — hearing Renaissance was confirmation of what we've always known in our heart of hearts, regardless of what society told us, or how our white peers made us feel: that to be queer, gifted, and Black is — as Nina Simone once intoned — a lovely, precious dream. And in Beyoncé's hands, it's the American Dream.

Beyoncé is the ultimate manifestation of what ballroom aspired to: the wealth, the glamour, the wigs, the O-P-U-L-E-N-C-E, as attained by a person of color. For her to say, in no uncertain terms, that ballroom is the bar — and that she is who she is because of the very people who worship and emulate her — is not just a renaissance. It's a revolution.

Uncle Johnny would be proud.

Sign up for Entertainment Weekly's free daily newsletter to get breaking TV news, exclusive first looks, recaps, reviews, interviews with your favorite stars, and more.

Related content: