Bestselling Author Jason Reynolds on His Books Being Banned: 'It Feels Insulting' (Exclusive)

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

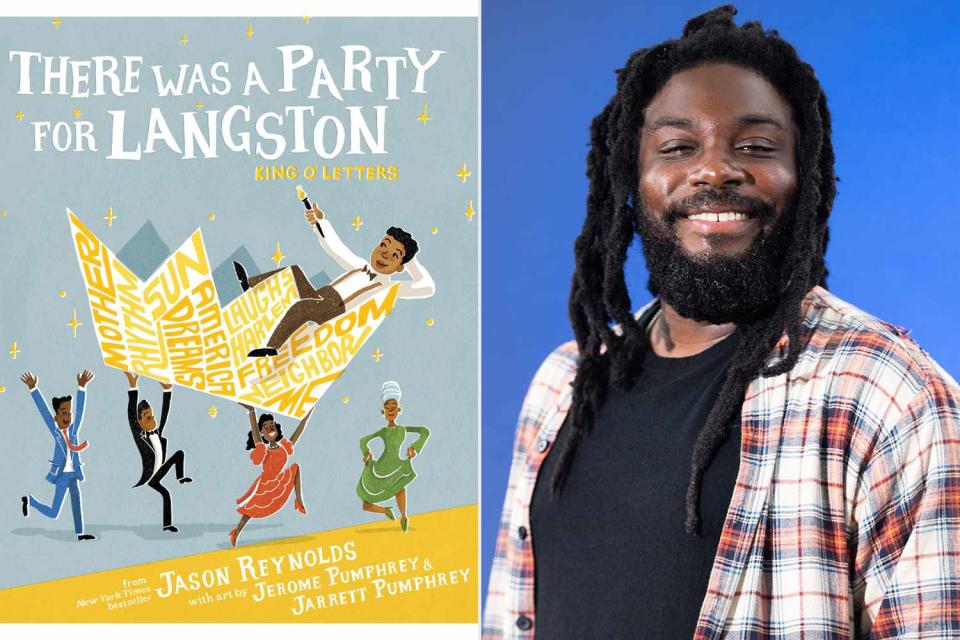

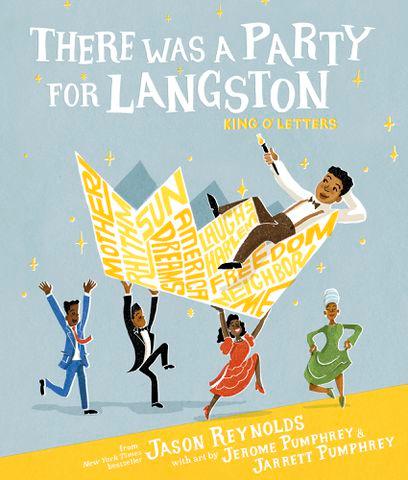

The young adult and middle grade author's debut picture book, 'There Was a Party for Langston,' is out now

Courtesy; Roberto Ricciuti/Getty

Jason Reynolds' debut picture book, 'There Was a Party for Langston,' is out now.A recipient of accolades such as the Newbery Honor, the NAACP Image Award and being named as the 2020-2022 National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, bestselling author Jason Reynolds, 39, has become an essential voice for young readers. His young adult and middle grade books, which include All American Boys, written with Brendan Kiely, Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You, written with Ibram X. Kendi and the recent Miles Morales: Suspended range from novels to nonfiction to comic book-inspired adaptations.

Now, Reynolds is delving into the world of picture books.

In his debut picture book, There Was a Party for Langston, out now, the writer pays tribute to the titular poet and activist. Including illustrations by Jerome Pumphrey and Jarrett Pumphrey, the book whisks readers to Harlem, to a celebration at the The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, where those influenced by Hughes come together to recognize their literary hero.

Reynolds sat down with PEOPLE to discuss his connection to Hughes, viewing writers as human and why book bans are "devastating" to him. Read the conversation below.

Can you remember the first time you encountered Langston Hughes?

When I was in middle school. I was asked to recite “I, Too." I remember being in the living room at my mother’s house and practicing to recite that poem. I remember rehearsing [and] my mother asking me what I thought the poem was about. What does it mean to be "the darker brother"? What does it mean to be sent away when company comes?

When you were in middle school, were you were one of the only Black kids, or the only Black kid, in the classroom?

I grew up in an all-Black neighborhood [in Oxon Hill, Maryland.] I was definitely one of many, many Black children. You had your February talks, your February lessons, but there wasn’t a lot of talk about the concepts around being "the darker brother." All these terms that we use to basically talk about Black people in service primarily to White people. I'm forced to grapple with something that I later find out is very close to my family. My grandmother was a domestic worker. My mother used to go with my grandmother to clean houses and with her grandmother to clean houses. That's a very real thing.

Hulton Archive/Getty

Langston HughesWhat did his work mean to you?

By that time, I had already discovered poetry, but [was also] reading rap lyrics at home and making the connection. I'm figuring out very young that these things are very much the same, and they're being talked about differently and they're being contextualized differently and they're being sensationalized in different ways. But as far as I'm concerned, in my 10-year-old brain, these things are exactly the same. Tupac's “Dear Mama” and Langston Hughes' “Mother to Son” could very well be a response to the other.

You start digging through Langston Hughes’s work, and you realize, man, this is the best way to begin a life in letters. To write something that feels simple, one must be extraordinarily talented. On the totem of my ancestors, I choose for him to be there.

Regarding the visual inspiration for the book, you’ve got [Amiri] Baraka and [Maya] Angelou dancing. What did you think when you saw that picture?

To see them together and to see them dancing, I knew immediately that it was special. There have been a few moments in my life where I realized that writers and poets are regular people and get to be regular people. I think there was a moment in the nineties where all of us felt like Esotericism was the way, and that if you cloak yourself in mystique, this was the way to be a serious writer. If you cloak yourself in moodiness, then this [is] the way to be taken seriously.

I remember one time being a 22-year-old and walking into the Prada store on Broadway in New York City. I had no money for it, just was curious to see what was happening in there, and I saw Saul Williams shopping. He was the king of young bohemians at that time, and here he was, buying high fashion. I thought to myself, "Oh, look at what we can do.” I don't have to be a particular way. I can be all the ways and any way. I can dance and I can go shopping and I can eat a burger if I feel like it. I can wear Jordans if I feel like it. I can cut my hair and shave my beard. I can do anything I want to do if I feel like it, because writers are just human beings.

Related: W. Kamau Bell Wants to Help Kids of Color Find Books to Inspire (Exclusive)

Rob Kim/Getty

Jason ReynoldsThat photograph represents not just the celebration of our collective hero [Hughes], but also a celebration that the hero was just a man. A man who liked to laugh and dance, which he wrote about often. He loved music and laughter and love and all the things that the human experience affords us if we are fortunate.

There's a section in the book where you talk about Langston Hughes. You say that he’s facing censorship and that people are trying to divide his words. We’re in a time right now with a lot of people making efforts to ban books, with a lot of those books being by Black authors and centering Black characters. As a writer, how do you fight back against that?

It’s always a tricky thing. I try to make myself available to the people who are actually on the front lines. [The] people who are actually doing most of this work are teachers and librarians. It's people with everyday jobs who go to work and fight this thing whose livelihoods are on the line.

Related: Meet the FReadom Fighters Taking On Book Bans and Online Abuse: 'Books Are Not Contraband'

We’re in a time where many people are banning books, including some of yours. How does that make you feel?

It feels insulting . . . and maddening. It hurts my feelings. You think I would write something that I deemed inappropriate or that I thought was harmful or unsafe for the most vulnerable and the most human amongst us? Absolutely not. I'd like to believe that I've been a part of creating a new generation of readers: literate young people, people who care about stories, people who care about their own stories and the stories of the people around them. People who are excited to know that they too can do this, much like I felt when I read Langston Hughes. I really truly believe this.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.