How Best Documentary became the Oscars' most unpredictable category

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When the 2021 Oscar nominations were announced in March, Kirsten Johnson's beloved, heartfelt documentary Dick Johnson Is Dead joined a proud lineage. Not those storied films that were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature, but rather those that weren't.

Though the shutout was certainly unexpected (nearly every pundit's predictions had Dick Johnson making the cut), a jaw-dropping omission in the Best Documentary race has long since become an Oscar tradition. From such classics as Errol Morris's The Thin Blue Line and Michael Moore's Roger and Me, to more recent cases like 2018's Won't You Be My Neighbor? and 2019's Apollo 11, the history of the Best Doc category is in many ways the history of what it has left out.

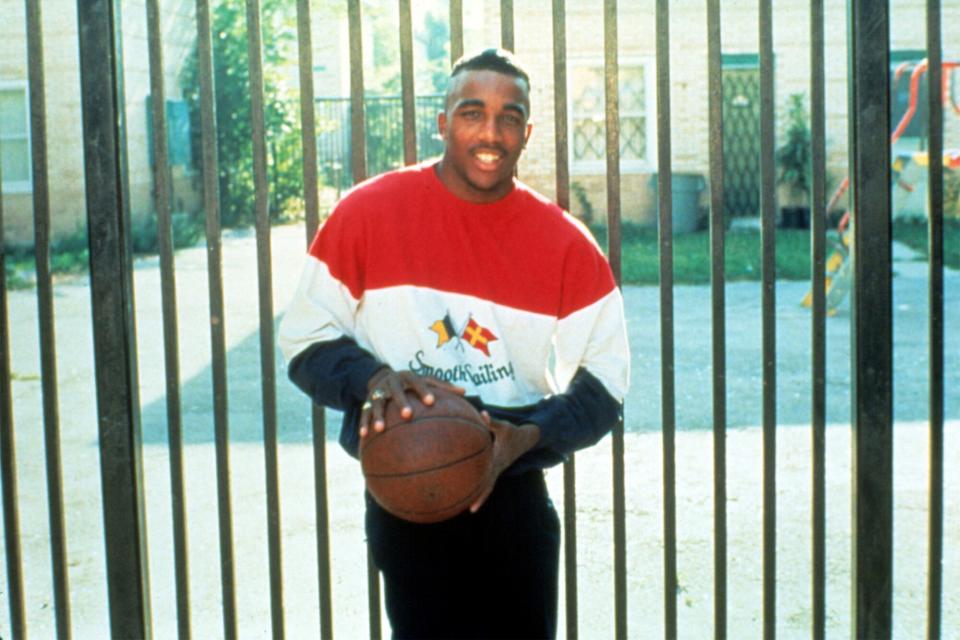

Indeed, it's not much of an exaggeration to say the Academy's documentary branch — the group of doc filmmakers and craftspeople who vote on the nominees each year — came into existence because of a snub. In 1995, Steve James' Hoop Dreams, which had been championed by influential critics like Roger Ebert, wasn't nominated for Best Doc, sparking an outcry and calls for reform that many perceived as long overdue.

"At that time, the documentary branch was run by a very small group of people who controlled who was in the branch. There were almost zero documentarians," recalls Peter Gilbert, a producer of Hoop Dreams. "We really were considered second-class citizens in the film world."

Everett Collection William Gates in 'Hoop Dreams'

In fact, there wasn't even an official branch: Academy members would volunteer to be on a documentary nominating committee each year, and those volunteers would view eligible films to determine what made the cut. Says Gilbert, "The way they decided was, they would get in a movie theater, and people had flashlights. And they'd put the flashlights on if they wanted to move on." (Ebert reported a similar anecdote in a 2009 article, adding, "Hoop Dreams was stopped after 15 minutes.")

"At that time, you had to show up at a theater and watch the films," adds James, who directed Hoop Dreams, "so it was a major commitment for people, and there was a sense that it tended to be older retirees [who volunteered]." (As Gilbert told The Dissolve in 2014, "I know some of the people who saw our film were hairdressers who hadn't worked for 25 years.")

James downplays the idea that Hoop Dreams directly caused the Academy to reform the process, saying it was simply "the straw that broke the camel's back." (Another highly acclaimed doc, Crumb, was snubbed the next year, which only heightened the furor.) It took another 16 years to establish an official documentary branch, in January 2001, putting doc filmmakers on equal footing with actors, fiction directors, and the other groups that vote for nominees in their respective categories. There was a sense of course-correction that followed: the oft-snubbed Moore and Morris won the next two years, for Bowling for Columbine and The Fog of War, respectively.

In 2012, the process was overhauled again, allowing the full doc branch to vote on both the shortlist of 15 contenders and the final five nominees. "Before then, it was a committee system where you were assigned certain films, and those were the only films you could vote on," explains Tom Oyer, a senior director of member relations and awards who's been with the Academy since 2007. "There was a feeling that branch members should be able to view all the films, and vote for any film that they love."

Radius / TWC '20 Feet from Stardom,' the 2014 winner for Best Documentary.

The changes also allowed the entire Academy to vote on the Best Documentary winner, regardless of whether they had seen all the nominated films (as had previously been required to choose the winner). The effect was quickly palpable, opening the door for more popular docs to triumph — at least temporarily. After a mini-wave of widely seen winners, including 2012's Searching for Sugar Man, 2013's 20 Feet from Stardom, and 2015's Amy, a new dynamic began to emerge within the doc branch.

"The change in tone has upset many doc branch members, as heavyweight issue films such as The Invisible War, The Square and The Act of Killing lost out to populist films about musicians and stars," journalist and filmmaker Adam Benzine wrote in a 2018 piece for The Hollywood Reporter. Benzine believes the conflicting taste of the branch and the Academy at large is now what leads to such films getting left out, citing Won't You Be My Neighbor?, 2017's Jane Goodall documentary Jane, and 2014's Life Itself, about Roger Ebert (which James also directed).

"There's a sense that the branch is deliberately voting against those because they don't want a populist winner," says Benzine, an Oscar nominee himself for the 2015 short subject Claude Lanzmann: Spectres of the Shoah. "Increasingly, there has been a push and pull in the category, between documentaries that are kind of slick, have high production values, and make you feel good, and then heavyweight films that deal with social issues."

It's this dynamic that may have hurt Dick Johnson, he adds: "I think there was always a sense that it's certainly a creative film, but that it's perhaps a bit slight."

Meanwhile, the field of docs competing for five slots has grown increasingly crowded; a record 238 films were eligible for Best Documentary Feature this year. "Ten years ago, when I was initially working in this category, you'd have about 70 or 80 documentaries that were eligible," Oyer says. "It's beyond exploded."

Netflix Dick Johnson in 'Dick Johnson is Dead'

And with that explosion of contenders, "There's been an explosion of money," Benzine says. "The year I was nominated in the short category, we were nominated against a beautiful film called Body Team 12. The team behind that spent something like $50,000 on a party in Hollywood to woo voters. And I remember, one of the other [filmmakers] I was nominated against was like, 'That's more than I spent making my film.'"

There's an "increasing divide," he adds, between financial powerhouses like Netflix and National Geographic, which poured millions into Jane's Oscar campaign in 2017, and smaller companies such as PBS that simply can't afford such lavish spending.

"It's turning into a mini-version of what goes on on the [narrative] feature side," says James, "and that encourages a kind of competitiveness that is not organic to our branch."

But it still seems money only goes so far in the documentary race. Jane, after all, made the shortlist but not the final nominations, and despite having "the 8,000-pound gorilla" of Netflix behind it (as James puts it), so did Dick Johnson.

"More and more, the people with the deepest pockets end up being able to build the biggest campaigns," says Roger Ross Williams, a current governor of the documentary branch who won an Oscar for his short doc Music by Prudence in 2010. "But I also think that every year, quality and the little film that could still rise to the top," he adds, pointing to smaller contenders like The Mole Agent, nominated this year, and Abacus: Small Enough to Jail, which finally earned James his first Best Doc nod in 2018.

"Here's the irony: Life Itself had a much more robust campaign than Abacus," James notes. "There was a major campaign mounted on behalf of that film. I did the whole song and dance — the screenings, the luncheons — and it didn't get nominated. On Abacus, when it got shortlisted, I was like, 'That's great; that's probably the end of it.' Everyone did what they could, but we didn't have that juggernaut at all. When we got nominated, it was like, 'Oh, wow! We got nominated!'"

Everett Collection Romanian doc 'Collective' became the second nominee for both Best Documentary and Best International Film in 2021.

There's one other major factor at play: More than any other, the documentary branch has fulfilled the Academy's promise to diversify and globalize its membership. About a third of the doc branch's nearly 600 members come from underrepresented communities, according to Williams, who also chairs the branch diversity committee. Another quarter are international, and more than half are women; the branch became the first in the Academy to achieve gender parity in 2018.

"It wasn't easy," Williams says. "I had to convince the members who had power, who had been running the branch, to accept this kind of change. Sometimes I get sort of beaten up for pushing for change too much, but it's reflected in our nominees every year, and that's an incredible feeling."

Indeed, the Best Doc lineup has grown increasingly international; only one American film was nominated last year, while this year's nominees include entries from Romania (Collective) and Chile (The Mole Agent). The doc branch also nominated the first openly transgender director in any category — Yance Ford for Strong Island in 2018 — and could award the first Oscar ever given to a Black female filmmaker on Sunday, should Garrett Bradley win for Time.

"We invite members who believe in the craft of filmmaking, and want to hold it to its highest standards," says Williams. "For me, what the Academy celebrates is always about craft."

But that persistent issue remains, of course: there simply aren't enough slots to reward all the superb films being made.

"I feel like it's time for the Academy to consider expanding the field of nominees for docs, the way they've done on the narrative side," James says. "It would be great if many as eight, nine, or 10 films could get nominated. It would be more fair to the wealth of terrific work being done, and it would be good for our art form in terms of our profile."

Until that day comes, it's inevitable that great documentaries will continue to be left out. But at least their creators can take heart that they're in good company.

Related content: