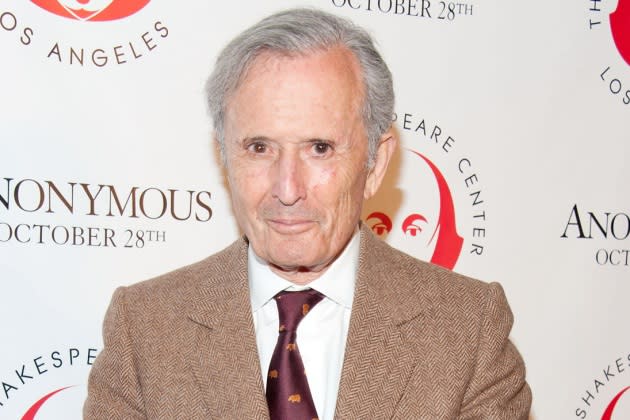

Bert Fields, Litigator to the Stars, Dies at 93

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Bert Fields, the renowned entertainment litigator whose clients included Edward G. Robinson, Jeffrey Katzenberg, Tom Cruise, Warren Beatty, The Beatles and a host of other luminaries, studios and talent agencies, has died. He was 93.

Fields died peacefully late Sunday night at his Malibu home, a spokesperson for his law firm, Greenberg Glusker Fields Claman & Machtinger Llp., announced.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

“For forty years, we were graced with Bert’s brilliance, decency and charm,” said Bob Baradaran, managing partner of Greenberg Glusker. “Bert was a beloved colleague, friend and mentor who trained a generation of outstanding lawyers. We were blessed to know and work with such a truly remarkable lawyer and human being.”

A longtime partner at Greenberg Glusker and mainstay on THR‘s annual Power Lawyer list, Fields during his six-decade career also represented the likes of David Geffen, James Cameron, Dustin Hoffman, Michael Jackson, Mike Nichols, Jerry Bruckheimer, Joel Silver and Madonna; companies such as DreamWorks SKG, MGM, United Artists, The Weinstein Co. and Sony Music; and famed authors including Mario Puzo, James Clavell, Tom Clancy, Clive Cussler and Richard Bach.

His early clients included Robinson — whom he represented in a 1950s divorce squabble over the sale of the actor’s Impressionist artwork — Elaine May and Peter Falk, and he formed an alliance with CAA co-founder Michael Ovitz around the time that agency was launched in 1975.

Feared around town, Fields became famous for facing down Paramount Pictures and protecting writer-director May’s final cut on her 1976 movie Mikey and Nicky — famous, but also notorious, because his leverage in the matter involved the mysterious disappearance of the only print of the film under circumstances that Fields perhaps engineered.

Indeed, the fact that he allegedly hopped a plane from New York to Los Angeles just as the print went missing in Manhattan suggested he might have been the bagman.

“I will not go into who did what,” Fields told The New Yorker in 2006. Said May: “He was what you always thought Perry Mason was. He did everything, and he did it without pay because I had no money. I paid him, finally, a year later, but he didn’t know I would.”

Fields never talked, but Paramount caved, and that was what mattered. Decades later, so did the Walt Disney Co., whom Fields litigated to a reported $280 million settlement on behalf of top film exec Katzenberg, who had departed the company after an acrimonious split with then-chairman and CEO Michael Eisner.

Katzenberg claimed that Disney had owed him a slice of the hefty profits from such animated hits as The Little Mermaid (1989) and The Lion King (1990). Fields’ questioning revealed that Eisner once had said of Katzenberg, “I think I hate the little midget.”

Fields told Los Angeles Lawyer magazine in 2015 that the best job he ever had was working in a stable as a teen — his worst was setting pins in a bowling alley — but it was obvious that he loved practicing law as well.

Fields represented Beatty when the director refused to cut four minutes from Reds (1981) so that Paramount could sell the film to ABC, and he won the case (Beatty had final cut). But when director Michael Cimino was ordered by 20th Century Fox to cut The Sicilian (1987), he took the studio’s side and won again (even though Cimino had final cut, too).

He also represented Paramount in its appeal of the Buchwald v. Paramount case over Coming to America (1988); obtained a multimillion-dollar judgment for George Harrison against his former business manager; and, representing DreamWorks SKG and Steven Spielberg, defeated an application for an injunction against the exhibition of Amistad (1997).

More recently, Fields represented Jamie McCourt against her husband, L.A. Dodgers owner Frank McCourt, in their 2009 divorce trial; negotiated Cruise’s 2012 divorce settlement with Katie Holmes; and represented Shelly Sterling against her husband, Donald Sterling, in asking the court to confirm her ability to sell the L.A. Clippers in 2014 (that’s when Donald called his wife “a pig”).

For Fields, winning clearly counted — he and his wife maintained homes in the Hollywood Hills, Malibu, New York, Mexico and France, and he was chauffeured to work each day in a Bentley — but his reputation took a hit when he was swept up in a scandal that began in 2002 around Anthony Pellicano, a “private detective to the stars” whose rough methods brought him more than a decade in prison for wiretapping, racketeering and weapons possession.

“Scores of people retained [Pellicano’s eponymous agency] for its often illegal services,” a federal appeals court wrote, and Fields had retained the P.I. many times during a period of two decades. Observers wondered what Fields had known of the dirty details — and so did federal prosecutors, who deemed him “a subject” of their investigation — but in the end, the lawyer was never accused of a crime.

Said Cruise in a statement: “Bert Fields was a gentleman, an extraordinary human being. He had a powerful intellect, a keen wit and charm that made one enjoy every minute of his company. I loved him dearly and always will. It was a privilege to be his friend.”

Katzenberg once said that “watching Bert was like watching a skilled surgeon.”

Said Bruckheimer: “Bert Fields, my lawyer, dear friend and trusted confidante for over 40 years, was one of the most extraordinary men I have ever met … Bert was that rare person who could achieve just about anything. He was a brilliant litigator, a scholar, lecturer, historian and author. He was extremely witty and charming with all the elegance of a true gentleman. But he also had the determination and grit of a street fighter. Bert Fields was a heavyweight. He accomplished it all with dignity and gusto and his indomitable zest for life and adventure.”

Born in Los Angeles on March 31, 1929, Bertram Fields was the only child of Mildred Arlyn Ruben, a former ballet dancer, and Maxwell Fields, an eye surgeon whose patients included Groucho Marx and Mae West. For a time in his teens, after his parents divorced, he lived in a boarding house and worked as a caddy.

At UCLA, Fields received a bachelor’s degree at age 20 and then his law degree three years later in 1952 from Harvard Law School, where he was an editor of the Harvard Law Review and graduated magna cum laude. He married his college sweetheart, Amy Markson, and served on the faculty at Stanford Law School.

Fields was in the U.S. Air Force during the Korean War as a first lieutenant — in England, he was assigned courts-martial — then began practicing law at a Beverly Hills firm in 1955, the year his son, James, was born.

Fields said he won his first jury trial, a case in which he “represented a man who had been accused of groping an undercover vice squad officer standing at the urinal of a skid row movie house.”

On a 1967 episode of NBC’s Dragnet, he portrayed a prosecutor (Jack Webb, the show’s creator, was a client).

A member of the Council on Foreign Relations and an adjunct professor at Stanford Law School, Fields also was an author, having published four novels — two under the pseudonym D. Kincaid — as well a biographical work on Richard III, a book analyzing the authorship of Shakespeare’s works and 2020’s Summing Up: A Professional Memoir, recounting his career.

When Puzo died while working on The Family, Fields finished it for him (Puzo had left him notes).

He also played the vibraphone for Hollywood’s Les Deux Love Orchestra.

After his brief marriage to Markson, he married fashion model Lydia Menovich, whom he met as a client, in 1960. She died of lung cancer in 1986, leaving the lawyer heartbroken. Ovitz ultimately tried to set him up with a friend, internationally known art consultant Barbara Guggenheim, at first to no avail, but Guggenheim later became a Fields client, and they wed in 1991.

She survives him, as does his son, John, and his grandchildren, Annabelle and Michael.

Many of Fields’ clients were larger than life, and he hoped to extend his reach into the afterlife as well. “There is a huge value in the post-death rights of performers, actors [and] musicians,” he said in a June 2015 speech. “I’m hopeful of representing synthespians.”