Behind the Scenes: Recognizing how Florida's policies can stifle artistic expression

I keep hoping that it will all blow over, that I will wake up tomorrow and we won’t be talking about banning books, forcing public libraries to withdraw from national accrediting organizations and dealing with laws meant to limit our ability to freely live our lives and understand our history.

Laws signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis limiting what can be discussed in public school classrooms and how history is taught, among other policies, led Equality Florida and the NAACP earlier this year to issue travel advisories, citing a hostile environment in the state for people of color and the LGBTQ+ communities. We should be concerned that these restrictive laws in the name of personal rights could be a precursor of worse to come. They are hostile to just about everyone, including those in the arts.

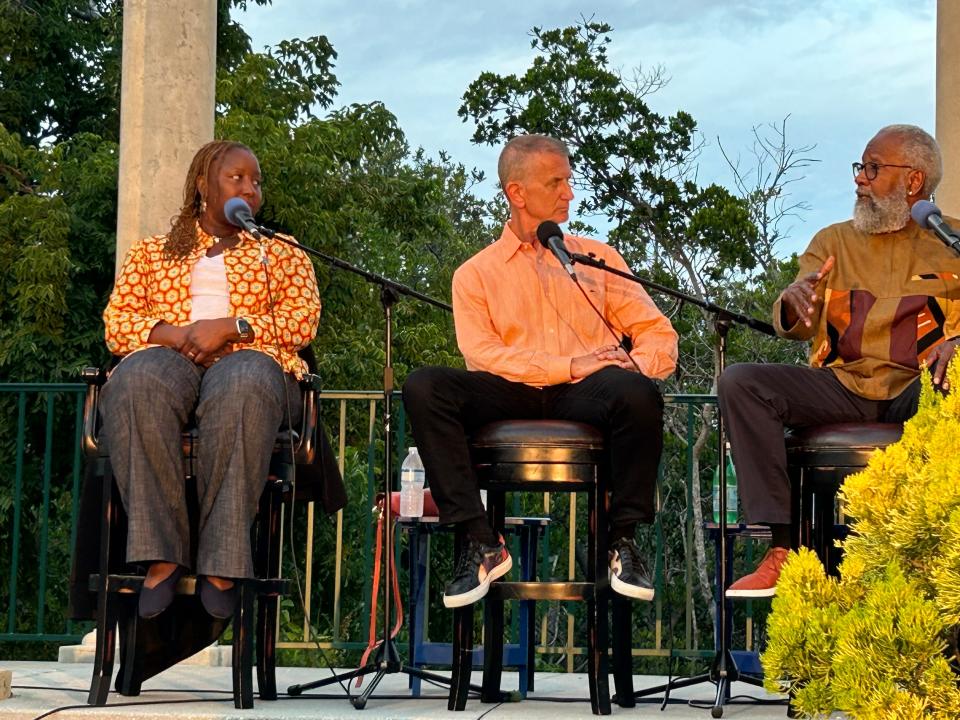

A recent program presented by the Hermitage Artist Retreat at Historic Spanish Point provided some perspective on how these policies impact the arts in Florida. It featured three impressive panelists – Nataki Garrett, former artistic director of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival; David G. Wilkins, president of the Manasota chapter of ASALH (the Association for the Study of African-American Life and History); and Tom Kirdahy, a Broadway producer and activist. All three offered examples that personalize the problems we’re facing. Kirdahy later expanded on some of his comments in a separate talk to the Longboat Key Democratic Club.

There are multiple issues involved, including worries that some artists and arts workers won’t want to move to the state because of their concerns about safety and free expression, which is essential to allowing creativity to flow. I know numerous teachers who have left the profession, or talk about leaving, because of how difficult it is to navigate vague new laws. Limitations on what can be taught, or what books are considered appropriate means that children, who are smarter and more aware than many adults will admit, won’t grow up with a full understanding of the world around them, socially, historically or culturally.

First-hand experience

Garrett spoke of death threats (and other hostile attacks) she received from people who didn’t like the kinds of plays and programs she scheduled at the well-respected Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland. It contributed to her decision to depart. She is now co-artistic director of One Nation One Project, an arts and health initiative that shows the benefits of involvement in the arts.

Wilkins spoke about his organization’s creation of the Freedom School, which it is offering outside the public schools to get around limitations on how Black history (and history in general) is taught. He also spoke about the ASALH’s decision to move forward with a national conference in Jacksonville after the travel advisories were issued. “We’re waking up the community. It’s unacceptable and we’re fighting back.”

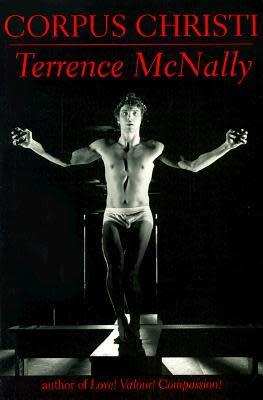

Kirdahy, whose late husband was multiple award-winning playwright Terrence McNally, shared a chilling story that illustrates the concerns we should all have about the future of the arts and culture.

In 1997, McNally wrote a play called “Corpus Christi,” which was set in modern-day Texas and depicted Jesus and his apostles as gay men. You can imagine how people responded to that. He became one of the most reviled artists since Andres Serrano, whose “Piss Christ” almost brought down the National Endowment for the Arts.

The attacks against McNally were stunning, with many people and religious organizations condemning the play without having seen or read it. All they had to see was gay and Jesus in the same sentence. The Manhattan Theater Club scheduled a production, canceled it and then opened it, but required audiences to go through metal detectors to get inside because of safety concerns.

Kirdahy said McNally was so stung by the experience he thought about ending his writing career. He felt he was being silenced.

That made me shiver. The thought that someone like McNally, who addressed a wide range of issues and was never shy about letting his feelings out through his characters in dozens of plays and musicals, might stop doing what he was born to do hit me hard. If he had stopped, how many shows would we never have known – plays and musicals that could well inspire future writers or other artists? It turned out to be a fertile period for McNally, who wrote nearly a dozen new plays and such musicals as “The Full Monty,” “Catch Me If You Can” and “Anastasia.”

If people don’t want to see his play, that’s fine. It happens all the time. We all have different tastes. But imagine if such attacks prevented us from discovering the next William Shakespeare, Arthur Miller, Eugene O’Neill or Terrence McNally?

Arts, health and creativity

Somehow artists always find a way. Theater will never die because there will always be people who have stories to tell. Others have a need and desire to get on stage and they have friends and neighbors who want to see them, as long as we’re not prohibited from doing so.

Arts are also important for our physical and emotional well being.

“People engaging with art are leading healthier lives,” Garrett said. “The arts extend your life and lower your blood pressure.”

We live in an arts-loving community and we know there are plenty of people who care about the culture, about what we can learn from the stories expressed in plays, music, dances, paintings and sculptures. We want people to have access to them.

But we have to worry that artistic leaders might become afraid to offer certain kinds of performances or exhibits because of laws and funding cutbacks. We have to be ready to encourage and support the artistic diversity we have come to appreciate here.

In his talk at the Democratic Club, Kirdahy noted that McNally was born in St. Petersburg and died in Sarasota in 2020 (one of the first prominent victims of COVID-19). Though he was raised in Texas, Kirdahy said Florida meant a great deal to McNally. But what about those who follow?

“Terrence achieved greatness in his lifetime and I am convinced that we can and must birth future great artists here in Florida,” Kirdahy wrote in his prepared remarks. “But we can’t do so in a climate of fear and bigotry. The talent drain will be too great.”

These are issues we can and need to address. There may be more urgent and pressing concerns at any moment – they are all around us – but we can’t let this slide if we want our society and culture to continue.

Follow Jay Handelman on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. Contact him at jay.handelman@heraldtribune.com. And please support local journalism by subscribing to the Herald-Tribune.

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Opinion: How Florida's restrictive policies affect artists