The beauty of Norney Grange – and why The Dig didn’t film at Tranmer House

The choice of locations in film and television dramas must occasionally excite the wrath of pedants: we have all seen Tudor extravaganzas filmed in Georgian palaces. Harder perhaps to understand is the use of Norney Grange, a fine Arts and Crafts house in Surrey by CFA Voysey, as the body double of Tranmer House, a handsome but pretty standard Edwardian Tudor revival house in Suffolk, in Netflix’s The Dig.

Until a Mrs Tranmer left the house to the National Trust in 1998 it was known as Sutton Hoo house, and was formerly the home of Mrs Edith Pretty, on whose land the eponymous dig took place in 1939. In possibly the greatest archaeological event in English history, burial mounds were excavated and a 7th century ship-burial was discovered. It is impossible to say definitively whose burial it was, but opinion tends towards Raedwald, a king of the East Angles who died in 624; and the ship contained the ultimate treasure trove of jewels, regalia, armour, buckles and clasps, all now in the British Museum.

It is a fabulous story, and ripe for dramatisation: but given the National Trust has Tranmer House, and are normally happy to let out their properties for highly remunerative filming, it is odd that they chose to use a house over 130 miles away, and in a conspicuously different landscape from that of East Suffolk. (Perhaps the Trust, given its current obsessions, was embarrassed by the thought that Anglo-Saxon kings engaged in pillage, slaughter and slavery, even though the people they sold into slavery were white.)

Tranmer House was built in 1910 by an Ipswich architect, John Corder (1856-1922) who specialised in mock Tudor, but who has left barely a trace, even in Suffolk. It is a perfectly fine house: but without imagination in its details and entirely derivative. Corder built it for a local artist, John Chadwick Lomax, who has left even less of a cultural footprint than his architect. It has the dimensions of a tall Tudor hall house, though none of its character of age. James Bettley, in his East Suffolk volume of The Buildings of England, barely notices it. Perhaps it was just too plain for Netflix.

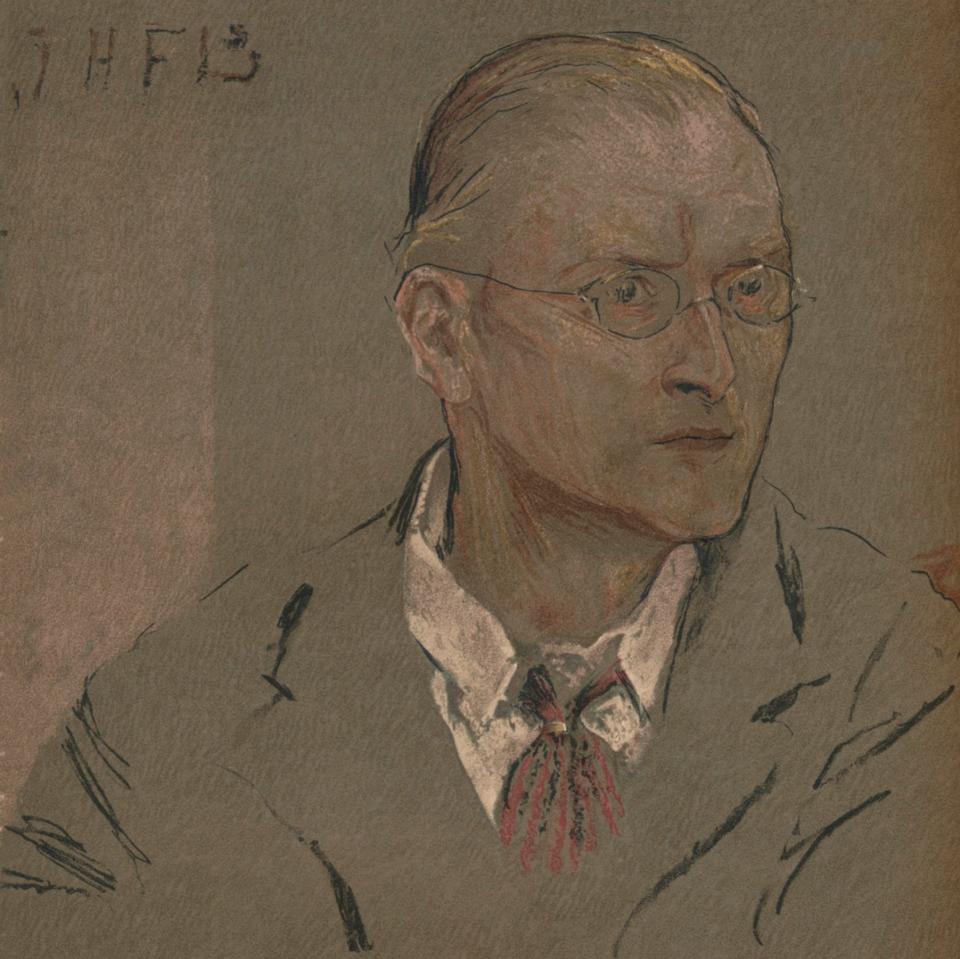

Voysey and his works were a different matter altogether; his houses are complete works of art, his style was his and it inspired countless houses built after he stopped designing domestic architecture in 1918. Charles Francis Annesley Voysey (1857-1941) was one of the greatest and most original architects of his era and a leading light of the Arts and Crafts movement.

He was exceptionally good at details – his locks, catches, hinges and other ironwork bear his own, unique design, and it was thus no surprise that he also designed fabrics, wallpaper, furniture and tiling for his houses that stood in a line of direct descent from William Morris.

However, anyone who examines Voysey’s work can see precursors of Art Deco: the wallpaper factory he built in Chiswick for Sanderson in 1902, now called Voysey House, could without shame have been put up 30 years later, and one or two of his early houses exhibit some of the curves out of place in late Victorian building, but entirely familiar from the 1930s.

Voysey built a number of fine small country houses, some in the provinces but mainly in the Home Counties. Norney Grange, at Shackleford near Godalming in Surrey, dates from 1897. It was built for a clergyman, the Revd Leighton Crane, and extended in 1903. In the Surrey Pevsner, mostly written by Ian Nairn, the remark about this house that "Voysey is here almost making clichés out of his own style" reveals that this was an architect by this stage in his career so confident of his abilities that he was almost able to parody himself.

The Dig is a wonderful film with Carey Mullligan, Ralph Fiennes and a strong supporting role by CFA Voysey's Norney Grange, Shackleford, Surrey, magically transported to Sutton Hoo @____fiennes____ @lilyjamesonline @netflix pic.twitter.com/6dwh3D4lMS

— Peter Murray (@PGSMurray) January 29, 2021

Nairn (for it is voice) adds that this much-gabled building has ‘typical long, low proportions, and typical low-key materials (slate, roughcast, and violent yellow limestone – this last an unhappy mistake for Surrey).’ He then points out that ‘the house also has Voysey’s disconcerting quality of appearing more solid the longer the viewer looks at it.’ The same is not true of Corder’s unadorned Tranmer House.

Russell Clapshaw, the current owner of Norney Grange has written that Voysey built several houses around Godalming, the area in the second part of the 19th century having become a magnet for the newly affluent following the arrival of the railway to London. Sutton Hoo House, with its great skies and open landscape, is very much what one would expect an artist to want to be built for him, in a ideal place for him to practise his art.

Mr Clapshaw also says that Voysey was experimenting at Norney, "trying to discover the Englishness in architectural style". By this he seems to mean that Voysey cherry-picked aspects of historic styles: Tudor leaded windows, Gothic inglenooks and allusions to ogee arches.

He points out that although Voysey did design everything as usual, all his design was functional: it served a purpose, as locks, hinges, cupboards and fireplaces usually do. Perhaps the great example of functionality at Norney Grange was the billiard table Voysey designed for it.

The game was at the height of its popularity in Edwardian England; the architect may have designed what appeared to be incarnations of the English nostalgic fantasy, at Norney Grange and elsewhere, but Voysey sought always to design houses and contents that were entirely suited to the contemporary life of the well-to-do people he and the other leading architects of his time built for.

It was a time when the rich had never been so rich, and even those earning £5,000 a year – more than half a million in today’s money – paid a top rate of tax at the end of the 19th century of two shillings in the £, or 10 per cent: so they could afford Voysey’s meticuluous inventiveness. Perhaps Mr Lomax lacked either Mr Crane’s deep pockets, or the imagination to commission a more exciting architect.

One can see why Netflix liked Norney Grange: to its predominantly American audience, weaned on the overblown absurdities of The Crown, it represents the English nostalgic fantasy. That audience might miss the practicalities of what Voysey was doing, but they will note his homage to the centuries that came before him. For all Corder’s solidity and restraint, Tranmer House could simply not do the same.