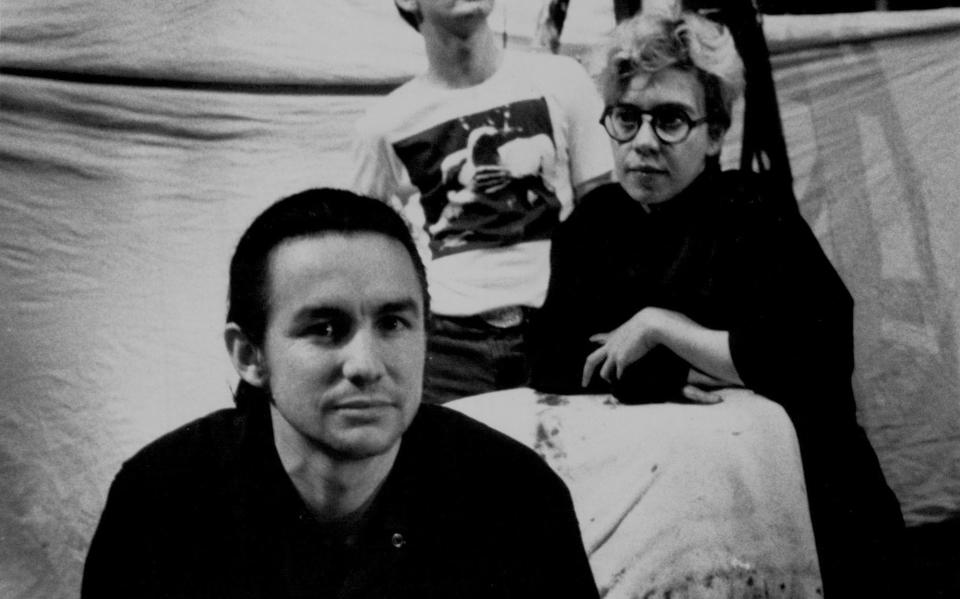

Baz Luhrmann & Costume and Production Designer Catherine Martin

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Director Baz Luhrmann first made his mark on the film world with the delightful 1992 musical “Strictly Ballroom,” but 1996 was when audiences got a taste for the full array of his boundless cinematic enthusiasms. Unleashed by the resources and scale afforded by a Hollywood studio, “Romeo + Juliet” would set the template for the director’s maximalist aesthetic, bringing together Shakespeare, music videos, Hong Kong action flicks, and Westerns. In the same way he later brought 1800s French can-can into the MTV era with “Moulin Rouge,” these seemingly disparate ingredients coalesced in Luhrmann’s head — where the lines between high and low culture, classic and contemporary art, history and fantasy, do not exist.

The key to Luhrmann’s sustained success across three decades — in which he is one of the last auteurs whose recognizable brand of cinema remains bankable — is a partner, both in life and work, who can extract a tangible story world from his fertile imagination. Costume designer, production designer, and producer Catherine Martin describes her own role in their collaboration as “visual translator,” with the ability to sketch (literally) her husband’s wild dreams into reality.

More from IndieWire

“I don’t know how she does it,” Luhrmann told IndieWire in an interview about his 35-year partnership with Martin. “I’m not joking. My mind wanders, it’s very hard to focus.”

Martin is more than interpreter — she is the co-artist creating the color, texture, and architecture that are the foundation on which she and Luhrmann tell their stories. She loves examining the problem at the core of any design project: “How am I going to take this ephemeral idea and actually make it a reality within a timeframe and budget, and actually be a true reflection of what the person is asking you for? And are you going to be able to improve on what they actually wanted?”

The exuberance and passion that yield the abundance of visual pleasures in Luhrmann’s movies can go so far that he is occasionally untethered from reality — but Martin has found a way of protecting and expanding upon his ideas while still keeping all departments levelheaded about what actually needs to be done. “It’s all about keeping the mind from wandering off into a sort of fantasyland,” Luhrmann said.

Martin, who has won four Academy Awards for her work on Luhrmann’s films, could certainly work with other directors, but finds herself sticking exclusively with her husband because his fearlessness inspires her own work and expands its horizons. “It’s about the discovery and about pushing yourself beyond where you expect to be,” she said.

To see those ideas in action, and for a snapshot of how they came to life, watch the video below.

It is the best kind of collaboration, one in which two brilliant artists are made better by responding to and elaborating on each other’s ideas. It’s a dialogue that began almost instantaneously when they first met. From the clothes to setting, to the star-crossed lovers’ meet-cute moment, the origin story of how the creative partnership began feels like a scene out of one of their movies.

It was 1987, in Sydney: Martin had booked a job interview with Luhrmann, and she was running late because she’d made her own outfit for the meeting and was still sewing the buttons on as the start time approached. “It was before cell phones, so I just left a message on his answering machine,” Martin said. “And I remember standing there ringing the doorbell going, ‘Damn, I’ve lost the job.’”

Luhrmann had been a student a couple of years ahead of her at Australia’s National Institute of Dramatic Art, and he was well known for a play he had devised during his time at the school called “Strictly Ballroom.” “He had won the international theater competition and he was just Mr. Important,” Martin said. “He’d come to talk at the school and we had to sit there adoringly watching his play, which was very good. But of course, it’s kind of irritating, and I just kept thinking, ‘What kind of a name is Baz?’” He was aware of her, too, and was impressed by Martin’s own student work. “I had an opera company, and I was one of those young enfant terribles, you know, sort of annoying,” he said. “I wanted to seek out emerging talents, and I’d heard about this extraordinary girl who did a performance piece where she designed a fridge that ate her.”

They’d agreed to meet at the office Luhrmann shared with his longtime writing partner, Craig Pearce, located above a brothel in the red-light district of Kings Cross. As Martin tells it, she was still ringing the doorbell when she heard a voice greeting her from behind. “I nearly had a heart attack because I was so in my own little world,” she said. It was Luhrmann, who’d just returned from a swim with Pearce.

“I was like, ‘Well, this is unfortunate,’” Martin said. “I’m all dressed to the nines and you two are in your sluggos, your towels, and your thongs.’” Martin’s attire left a more positive impression: “She had this amazing linen suit,” Luhrmann said. “I remember noticing a thread coming out of the top of her jacket, and it occurred to me that she might have made that suit.”

After getting dressed and dismissing Pearce, Luhrmann sat on the floor of the office with Martin — and they began a wide-ranging conversation about art and life that’s still going today. As they spoke of Bertolt Brecht and Madonna, Luhrmann remembers thinking, “I don’t really want her ever to go out of my life.” Martin quickly came to feel the same way. “When I met him, I suddenly went, ‘Oh, at last somebody who talks the same language,’” she said. “I felt like finally I had connected with someone who felt about art and theater and film as I did, and that was incredible.”

Martin went to work for Luhrmann on his experimental opera “Lake Lost,” and moved on to design sets and costumes for a new production of “Strictly Ballroom,” during which she constantly fretted about being fired due to her inexperience. “They were terrified that I had no idea what I was doing,” she said. “And to some extent they were totally right, but I’m incredibly tenacious and I just hang on for dear life. I worked and worked and worked and worked, did whatever it took, and eventually I remember our producer saying, ‘Wow, you’re doing a really good job. We’re really up against it in this scene. What do you suggest?’”

The scene in question, set in a dressing room, tasked Martin with executing Luhrmann’s vision despite limited resources. Together, they worked out a system inspired by the way Orson Welles had created an illusion of space. “We were very influenced by the making of ‘Citizen Kane,’ where Welles used scenery pieces out of stock and would light them — whether it was a staircase or a fireplace — and then there would be a black void between those two things that kind of stitched them together with black drapes. That’s one of the things we used in ‘Strictly Ballroom’ to stretch the budget — we kept using red velvet curtains over and over again to create all kinds of different spaces.”

Watch the video below to see how Martin’s ingenious solution translated to the screen version of “Strictly Ballroom.”

“Strictly Ballroom” was the first (but certainly not the last) time Martin found a production-friendly way to stretch Luhrmann’s canvas to match his vision. It begins at the pre-visualization stage, with Martin working from Luhrmann’s rough sketches. “I wish I could draw like DaVinci, but I can’t,” Luhrmann said. “I scribble badly. C.M. says ‘Oh, they’re very emotional drawings, darling, they’re so clear.’ They’re not. I don’t know how she sees it because I can’t even read my own handwriting. Can you imagine how impossible it is to read my sketches? But C.M. is so good at practical solutions to things.”

Those solutions often involve reconciling seemingly opposing ideas. With “The Great Gatsby,” for example, Luhrmann wanted the film to be honest to its 1920s period setting, yet still feel immediate and contemporary. Martin looked to fashions from the ’20s that she felt were somehow linked to contemporary style, and worked with collaborators from Brooks Brothers and Prada to merge the retro and the contemporary, leading to striking designs like the “chandelier dress” worn by Daisy Buchanan (Carey Mulligan). Marveled Luhrmann, “I don’t think there is anyone on the planet who knows more about the history of fashion, or how things are made than Catherine Martin.”

The detail work of a costume might not seem like the cornerstone of the “Gatsby” world-building challenge, but such details are the world-building on a Luhrmann set. Daisy’s chandelier dress not only fused Jazz Age elegance with sparkling modernity, it was is in visual conversation with the ornate lighting fixtures of the production design, speaking to another aspect of Luhrmann and Martin’s filmmaking philosophy: “A lot of times clothes [are] the set because a third of a movie is basically a close-up,” Martin said. “So what you’re really seeing is the collar of someone’s outfit. The buttons on a man’s shirt.”

If Luhrmann’s preproduction process is one of collage — adding a wide array of photos, videos, and art to the historical references grounding his worlds — it’s Martin’s ability to find ways to merge these disparate sources of inspiration into a single detail that allows them to be successfully rendered on screen. But the director sees its importance as even greater. “There is no delineation between the set and the costume and the hair, and therefore between the character and the actor,” said Luhrmann. “There is no choice that isn’t made that isn’t in a subconscious way amplifying the scene.”

A perfect example of this merging of world, character, and costume is the way Martin collaborated with Luhrmann and actor Austin Butler in “Elvis.” What the actor wore needed to unite Elvis Presley’s dual musical influences of rhythm & blues and country-and-western with his gender fluidity, while also showcasing the way Butler was using movement to embody The King. This all came to a head in the pivotal “Louisiana Hayride” scene: In order to sell the frenzy inspired by Presley’s star-making appearance on the influential radio program, they’d have to capture the visceral experience of his hip-swinging — but the clothes weren’t cooperating. After the director himself shimmied around in a few jackets that were truer to what Presley might have worn on stage at the time, he and Martin realized the jacket needed to shimmy, too. The obstacle they were facing was structure, so Martin suggested a top that was more akin to a giant cardigan — “just shoulder pads and fabric falling,” as Luhrmann described it. “And then click, we had it,” he said. “If that jacket didn’t move properly, no matter what Austin did you wouldn’t see it. You wouldn’t feel it.”

This speaks to what Luhrmann feels is one of Martin’s great strengths. “She’s brilliant at costume construction, she’s absolutely a genius. I don’t think anyone on the planet knows more about the history of fashion or how things are made.”

For more on Luhrmann and Martin’s “Elvis” collaboration, including the “Hayride” scene, watch the video below.

“Elvis” was preceded by a years-long research process that found the director interviewing Presley’s childhood friends and working out of an office at Graceland. “When I make a movie, I live the movie for five years,” said Luhrmann. “I kind of become the character in the world,” he said. Given how all-consuming it and other Luhrmann-Martin projects are, the question arises of where the couple’s professional life ends and its personal one begins. As with so many facets of their output, this may be one area where there simply are no dividing lines. Luhrmann finds it difficult to maintain relationships outside of work; what he cheekily describes as “the circus life” is all he’s ever known. If anything has changed from the days when they were cutting corners with drapery and flooding studio spaces in the name of experimental opera, it’s that they’re more upfront with one another, as Martin put it, about “where we are and what we need and where we’re going.” “It’s constant work and evolution and there’s no real recipe,” she said.

The upside of that intersection between life and work is that both partners remain inspired and challenged by each other. The conversation that began above a brothel in Kings Cross continues to find fresh tangents, giving moviegoers new reasons to appreciate centuries-old romantic tragedies, American-lit required reads, and pop songs they’ve heard dozens of times before. But first, each of these ideas must impress Martin and Luhrmann.

“Quite often I’ll be in a really grumpy mood or have found something he’s done irritating — like anyone does in a really long working relationship — and then I’ll see something that he’s done and just be absolutely mesmerized and surprised,” Martin said. Reflecting on her admiration for her husband and what they’ve created together, Martin cracked an aside. “I know: ‘So what, his wife thinks he’s amazing,’” she said. “But I actually do think he’s amazing.”

They are devoted, adoring, united. “But we also have this other thing that we can join in and fly above all the things that usually bring couples down,” Luhrmann said. “We have the art, and it gives us wings.” –Jim Hemphill

Best of IndieWire

Where to Watch This Week's New Movies, from 'Dumb Money' to 'Cassandro'

The Best True Crime Streaming Now, from 'Unsolved Mysteries' to 'McMillions' to 'The Staircase'

Martin Scorsese's Favorite Movies: 70 Films the Director Wants You to See

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.