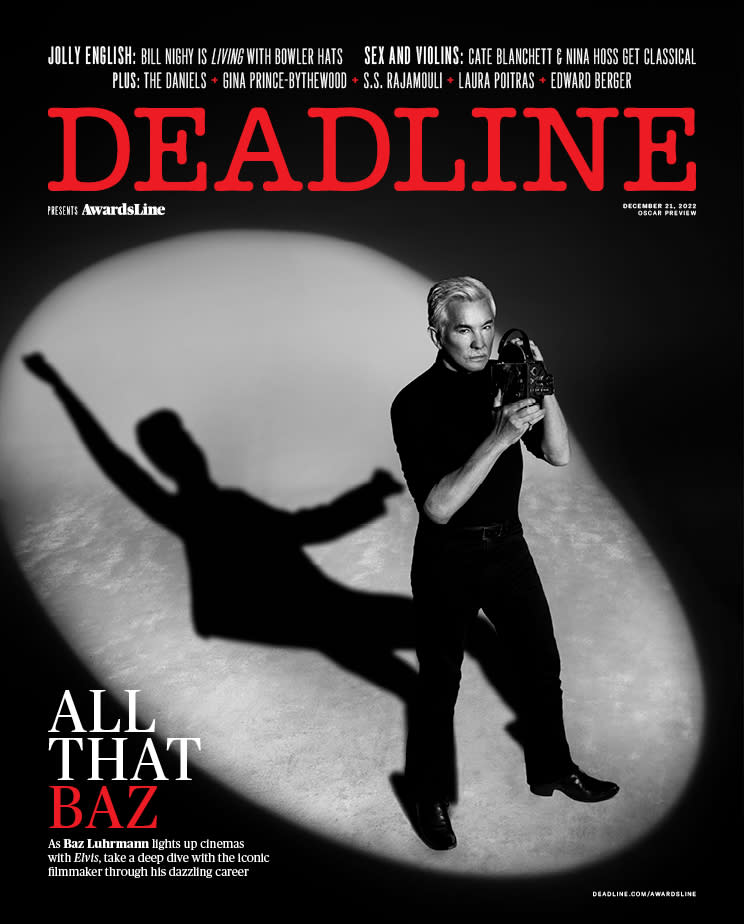

All That Baz: How Baz Luhrmann’s ‘Elvis’ Tells The Truth Behind An Icon Who “Just Wanted To Love And Be Loved In Return”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The night Baz Luhrmann premiered his film Elvis at the Cannes Film Festival, all eyes were on Priscilla Presley. She had turned 77 the day before, and in the 45 years since her former husband’s death, she’d suffered many cartoonish caricatures and lame imitations of the man she loved. But that night, as the credits rolled, she cried.

Luhrmann was relieved; after all, Presley’s blessing wasn’t something the director took for granted. “I really mean this with great respect, because now we’re like family,” he says, “but she got a little bit vocal about her doubts. She said, ‘I don’t know, this film could be crazy. Baz can be wackadoo. And how can this skinny kid play Elvis?’”

More from Deadline

The “kid” she referred to was Austin Butler. And her concern was understandable. How could she trust anyone to depict the man she loved; the tortured and brilliant artist who changed music history? He was a man both complex and self-destructive, with a huge, fragile heart. As Luhrmann says, “Elvis had become wallpaper. He was sort of a Halloween costume. But to his family, he was always a husband, a father, a grandfather and a person.”

On top of that, Luhrmann wasn’t planning some puff piece of cinema about a beloved icon. Instead, he sought to look behind the velvet curtain. “There were things that were going to be difficult for them to see about Elvis, but they were also going to see the humanity and true spirituality of him, which was the most important thing.”

After seeing the film, however, Presley wrote Luhrmann a letter. “I won’t share all of it,” he says, “but the key thing she said was, ‘My whole life I’ve had to put up with people impersonating my husband, and I don’t know how that boy did it, but every move, every wink… If my husband was here, he’d say, ‘Hot damn, you are me.’”

Baz Luhrmann likes to live his movies, and Elvis was no different: in the course of making it, the Australian moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where he visited Graceland, Elvis’s home, took a dive deep into the singer’s archives, and even found the man who had been with Elvis on the day he discovered the power of Gospel music.

His mission was to show us the lost boy behind the mask, but he would frame it as “a canvas to explore America” — and crucial to that was the relationship between Elvis and his manager, Colonel Tom Parker (played by Tom Hanks in the movie). A former carny, Parker used both financial and coercive control to line his own pockets, while depleting the artist’s mental and physical health, until in 1977, when the 42-year-old Elvis — the bestselling solo music artist of all time — died of a heart attack, likely caused by his reliance on barbiturates.

Says Luhrmann, “The Colonel represents the great sell in America, and this therefore made it about America: the sale of the soul, the artist and the ringmaster.”

Surprisingly, when producer Gail Berman first approached Luhrmann about an Elvis project, he hadn’t been sure. “She’d managed to get the rights to the estate, and she said, ‘I’ve got this one idea.’ I said, ‘Well, what is it?’ She says, ‘It’s you.’ And she never gave up. Then, when I told her my idea about the Colonel, she dogged me even more about it.”

Having cracked the subtext, there was still a long way to go: where do you find an actor with the range to play that kind of icon? Luhrmann originally set about workshopping Harry Styles and Miles Teller for the part. But then came this former Disney actor, Austin Butler, for whom getting the role felt almost tinged by magical intervention.

“I had never heard it before in my life,” Butler says, “but in the month prior to hearing about Baz making the film, an Elvis Christmas song was on the radio, and I was kind of just goofing around, singing along to it. And my friend said, ‘You’ve got to play Elvis.’ But it was such a long shot, I just laughed and pushed it to the side. And then a couple of weeks later I was playing the piano, and my friend said, ‘I’m serious. You’ve got to figure out how you can get the rights to maybe write an Elvis film or something.’ I said, ‘That’d be amazing, but there’s no way that that’s going to happen.’”

A week later, his agent called and told him about Luhrmann’s film.

“Well, immediately I got chills,” Butler says.“Because of the synchronicity of it all, I thought, ‘I got to just give it everything I got.’ So, I started prepping from that day as though I was going to be making the movie.”

The first thing he did was send Luhrmann a self-tape. “It came out of this detail that I learned about Elvis,” Butler says, “about his mom, who passed away when he was 23. That’s how old I was when my mom died, so I ended up filming this tape that came out of a nightmare that my mom was dying again. It was an emotion of such deep pain. It kind of stripped away the icon of him, or the caricature of him, and it just made him so human.”

This was precisely the depth of Elvis that Luhrmann sought, and Butler was so right for the role that Luhrmann doesn’t even recall offering it to him. “I just remember the moment he walked in,” he says. “Then one day we made the movie.”

Luhrmann had originally planned to have a voice impersonator perform as the young Elvis, because he didn’t have the rights to use those original recordings. Nevertheless, he asked Butler if he could sing. “Austin said, ‘Well, I don’t really sing but I’ve practiced one Elvis song… ’” He pauses. “I’ve still got it on video. I mean, when you hear him sing, it’s crazy. You cannot believe. It’s spine-tingling. We just started riffing, and hours would go by.”

Butler returns the praise, describing Luhrmann as a great collaborator. “Baz has this extraordinary quality where he doesn’t have a barrier between life and art,” he says. “He lives the art life. David Lynch talks about that, and I think Baz is very similar: there’s this never-ending poetry of the art, and you see how it flows into his life and vice versa. So that’s an amazing quality to be around, because you don’t feel like you’re ever breaking into something else. The two are one. And it’s also a way that I really love to work.”

Finding the right actor to play Colonel Parker was equally fortuitous. Casting Tom Hanks so severely against type would only serve to highlight Luhrmann’s message: how, as with Elvis, a star can be constrained by audience expectations. He says of Hanks, “Once you start to be something avuncular, everybody wants that tune from you, a riff on that part of you as a performer. My joy is finding actors and helping them play a tune no one’s ever heard.”

He recalls that Hanks came on board shockingly fast. “An actor like that, to get them to do a large role like that, could take you a month of talking and convincing and cajoling. I went in to see him at Playtone, and I said, ‘Colonel Tom Parker’s like a clown with a chainsaw.’ I had a video of Parker, and I had all these props to start convincing Tom to do it. I never got the video out. He stopped me in the middle of it. He talked a bit about the character, and he went, ‘Well, if you want me, I’m your guy.’ It must’ve taken 20 minutes.”

Luhrmann’s theory as to why Hanks was so sold on the sinister Svengali role is this: “I think he’d got to such a place in his life that he knew by playing Colonel Tom Parker he would have an extra level of distastefulness from his fanbase, because it’s a bit like your favorite dad turning out to be corrupt. I think he wanted to take that step and break the expectations, because he’s truly one of the great actors of all time.”

Significantly, Luhrmann uses the Colonel’s point of view to frame the movie, a device he compares to the 1984 Miloš Forman-directed Amadeus, in which the story appears to be led by the ill-fated Mozart, when in fact it’s the twisted and jealous Salieri who tells the tale.

“It’s not Amadeus’s story,” Luhrmann says. “Salieri is saying, ‘So let me get this right, God. I was chaste. I made a deal with you to give me the gift of music. And I’m king. I’m loved. And then you go and put genius in that little pig? How’s that fair?’ And then you have the preposterous conceit in that movie, like, ‘Right, I’m going to wear a mask and get Mozart to write the Requiem to kill him.’ Now, you have to have a stupid idea like that so that you can explore the bigger idea, which is, in that case, jealousy. In the case of my movie, it’s basically the selling of the soul. It’s talent versus promotion, really.”

So now he had the theme, the cast and the dramatic tension. But at the heart of all of Luhrmann’s films, there’s always a love story. And Elvis’s is not the one you might expect.

“Very early on,” says Luhrmann, “a young guy working with me on the music said, ‘Look, I really like what we are doing, but every movie you’ve made has had this great romance in it. And you’ve got Priscilla in it and the Colonel. Is the romance really the Colonel and Elvis?’ And I went, ‘Well, Priscilla, absolutely. The Colonel and Elvis? Yes.’”

But now, looking back, Luhrmann sees that it’s something else. “I’ve just realized, the true love story of Elvis, and the way it fits into the oeuvre, is between the audience and Elvis. It’s actually about his addiction to this love: the more you get, the less love you actually feel. It’s a destructive love. Because in the end, Elvis Presley is not that child who runs around and just can naturally sing and everyone goes, ‘Oh, you’re great.’ He keeps developing a character, and then, at some point, he can’t take that character, the mask, off. But he has that addiction to the audience, and the audience’s complete need for their icons to stay eternally young, to do another album, another song, another movie… ”

In trying to figure out the man under the shades and the rhinestone jumpsuits, Luhrmann found an extraordinarily talented, deeply spiritual person who spent his life trying to mitigate old pain. The film takes us back to Elvis’s beginnings in Tupelo, Mississippi, and later, Memphis, seeing the hardship of his home life. “There’s a big hole in his heart from childhood,” says Luhrmann, “from the shame of his father going to jail, from being in one of the white houses in the Black community, all of that. He’s trying to mend his life constantly, trying to be liked and getting people to like each other. And ultimately, that’s going to end in self-destruction.”

There’s an important scene where a very young Elvis ventures into a Gospel service with a friend, and the friend instinctively tries to pull him back, as though they don’t belong there. But Elvis is captivated, and the preacher says, “Leave him be, he’s with the spirit.”

That friend was Sam Bell, and, unbelievably, while living in Memphis, Luhrmann turned investigative reporter and tracked Bell down, getting that story firsthand.

“One of the family members knew of him,” he recalls. “We got an address. I sent a FedEx. Nothing. We drive around to the house. It’s raining. And I could see the FedEx is wet from three days of rain. It hasn’t been touched. And the house looks pretty unused. So, I said, ‘Look, he’s not here.’ And one of the young guys says, ‘So let me get this right, we’ve come all the way to Tupelo, and you’re not going to get out of the car?’ I get out the car, there were cobwebs around the door. I thought, ‘Well, he’s clearly passed.’ And then the same young guy said, ‘We’ll go round the back, then.’ I’m like, ‘Don’t get arrested. I’m Baz the coward.’ Unbelievably this older lady comes out. I said, ‘I’m looking for Sam Bell.’ She says, ‘Yes, I’m his wife. He’s been in hospital for six months, but he’s coming out next week.’”

Bell was a veritable goldmine. “Sam told me a whole lot, actually. I mean, there’s more than I put in there about how he and this kid called Smokey used to fight all the time. And Elvis was a bit of a story maker-upper because he was so embarrassed about the fact that his dad had been off in jail. Sam said, ‘My grandparents adored him. He called them sir and ma’am. No white person in those days, man, woman, or child ever said that to my grandparents.’ They just thought he was the most magical, unusual, sweet and vulnerable, but kind of cocky kid they’d ever met.”

Bell passed away in the fall of 2021. “The revelations were so authentic,” Luhrmann says. “And he never asked for money. He just told the stories.”

Luhrmann thought a lot about them, and the pain that dogged Elvis. He sees it as a throughline to a universal human experience: the need to fill the emptiness, to manage shame, to love and be loved.

“That’s what the Greeks call pothos,” he says, “and that is, the more love that you seek that’s not internal, the more adoration you need. It’s a drug. [Overcoming it] is a life’s work. And you probably don’t start to deal with that until you’re at least 40. Because before 40, you’re going, ‘Am I someone?’ And you’re just so focused on getting it. And then when you get it, you’re like, ‘Hang on, I thought this would fix things. No. Sh*t. Well, how do I fix things?’ The external thing probably helps you a lot because it’s self-medication of a feeling of insecurity and not being good enough. I mean, we see them, they’re all poster boys for it, whether it’s Michael Jackson or Napoleon. They just keep going, they keep pursuing some impossible goal that ultimately destroys them.”

There’s some footage of Elvis from the very last time he performed on camera. He’s singing “Unchained Melody”, and two years before he shot the movie Luhrmann knew he wanted to use it. “He sings the best he ever sings,” Luhrmann says. “It’s so moving that that’s the death scene. That’s the farewell.” But Authentic Brands Group, who control the licensing and merchandising rights to Elvis Presley, did not want it to be shown.

Fortunately, Gail Berman came to the rescue and persuaded them to agree. Luhrmann says, “They actually said, ‘Look, we trust you so much if you really believe that. But we’re scared of it because Elvis is so unattractive in it.’ He’s discombobulated. He can hardly put two words together. I said, ‘Well, if you don’t want to do it, I’ll get Austin to do it.’”

Butler came through. “Unbelievably, he just absolutely studied it and channeled it, even in the costume test,” Luhrmann says. But Luhrmann knew he still wanted to follow the biopic trope of showing the real artist at the end. So, he cut from Butler’s version to the original. “We knew we had an emotional beat-change; we knew we really had something.”

Says Lurhmann, “There’s a moment when Elvis is singing the song and he looks to the audience and he smiles like a little boy: ‘Am I doing good? Am I good?’ And you realize that there’s still a little boy in there trying to make up for a dad going to jail, trying to please and be loved, and have people love each other. It’s so childlike. And then we cut to the real Elvis. I mean, we could have run through with Austin, but I knew we were going to miss the really important final thing: Austin’s humanized Elvis in a way that I don’t think Elvis has been humanized for so long. You have to remind people that it’s OK that his body was corrupt and all the discombobulation with the drugs. Inside was still this beautiful kid who just wanted to love and be loved in return.”

A Little More Conversation …

Baz Luhrmann takes a walk through his 30-year career in film.

The day before this retrospective interview, Elvis director Baz Luhrmann was approached by a super-fan. “The guy was so nervous,” he recalls, smiling. “And it reminded me of what movies meant to me when I was younger. Like Saturday Night Fever or Apocalypse Now: those two movies were everything to me. I’ll never be able to get those movies out of my DNA, which is why my films tend to be like Saturday Night Fever musicals made at the scale of Apocalypse Now,” he laughs. “Apocalypse Now: The Musical, anyone?”

Don’t rule it out. Here, he looks back on 30 years of filmmaking and the steps that led from a low-budget feel-good romcom set in the boondocks to a blockbuster biopic of the king of rock’n’roll…

Sidebar by Damon Wise.

Strictly Ballroom (1992)

A rebellious young ballroom dancer defies the rules of the Australian Dancing Federation in the hopes of winning a major championship.

I come from an acting-teaching background, and Strictly Ballroom was born while I was at drama school. We were taught how to create collaborative environments and how to make our own work. Strictly Ballroom was a work that I did based on a primary Greek myth: the idea of triumph over oppression, and also the myth of the ugly duckling. I had this idea of placing it in a world that I understood, and I understood the world of ballroom dancing very well because I grew up in it, in this tiny country town in New South Wales. I devised it with a group of actors; I’d set out the architecture of the story and I’d come in with the actors every day. The original show was 20 minutes long.

After I graduated, the school was invited to a drama festival behind the Iron Curtain in Czechoslovakia, which was then just as Glasnost was hitting. We thought were going to be laughed out of the Soviet Union. I used to watch the other kids rehearsing; they’d be doing Chekhov’s The Seagull, and there we were with our funny ballroom-dancing play. But there was this underlying Brechtian message in the play, we used to actually turn to the audience and go, “Fuck the Federation!” and there were recordings of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher while we were changing into our Latin costumes. At the end of the show, there was a 40-minute standing ovation. They invaded the stage, all the satellite countries, because they reacted to the metaphor of oppression.

Years later, a guy called Ted Albert saw a longer version I did with my theater company. He had a band called AC/DC. You might have heard of them. He wanted to start a film company and he tried to buy the rights, and I said, “No, I’m going to direct it.” He said, “All right,” so I developed the script and got my old friend Craig Pearce to work with me. We were about to be green-lit, and Ted died, very tragically. The film was over, but then Ted’s wife Antoinette stepped in. We defied all the odds, just like the movie.

The film screened in Cannes, at midnight, and a large crowd pressed in on us. I’d never had that before. A security guard reached in and grabbed me. He dragged me through the crowd as they followed us down the Croisette and he said, “Monsieur, from this moment on, your life will never be the same again.” Actually, he was right.

People might say, “Well, it’s Dirty Dancing.” Or they might say, “It’s Rocky.” But those films were also taking primary Greek myths, these against-the-system, overcoming-oppression, transformative myths, using a fun or ironic kind of language that nonetheless disarms the audience and leaves them with a resonating — whether you get it intellectually or not — larger idea. I can say that now without it sounding pretentious. But when I said that when I was 30 it sounded very pretentious.

Romeo + Juliet (1996)

William Shakespeare’s tragedy is reimagined as a post-modern urban gangster movie.

I had an overhead deal with Fox, and Romeo + Juliet was certainly not what they wanted. I think everybody wanted Strictly Ballroom 2, But that’s not how I proceed. I have these ideas or things I want to do, and one of the things I always wondered, having been a scholar of Shakespeare — he’s my go-to, really, kind of my guiding light — was the question: if Shakespeare were here, how would he make a movie?

I’d done a crazy thing once in Australia, with a girlfriend of mine, where we went into a boys’ prison — more than a reform school, a place with serious offenders — and did a radical theater company. We did some scenes from Romeo and Juliet with the boys, and I thought they’d kill us. But it was amazing how quickly they took to the idea of playing both Romeo and Juliet. It was unbelievably freeing for them. I only remembered that the other day.

At the time I was thinking about my next movie, I was really focused on the idea of reinventing the musical. I really thought I could do that, but I knew it was going to be quite labor-intensive. I needed to learn more, to study musicals and learn more how to actually make or produce music. I thought, “Well, that seems too big to do right now. Why don’t I do something really small that I could knock off pretty quickly as a short adventure? What if Shakespeare made a movie?” That turned into an epic journey of unimaginable proportions, with me ending up in Mexico with 19-year-old Leonardo DiCaprio and a young Claire Danes.

One day someone should make a movie about the making of that film. I mean, we had our own army. We had things like our hair and makeup person being kidnapped, and us getting him back for $2,000. (Or was it $200?) Take the church scene where the helicopter attacks Leo. It was a real helicopter shooting at him, and it blew out all the windows in the local neighborhood. We shouldn’t have been there. And it was a totally real church. The candles were real, the neon lights were real. There was no artificiality. The final shot at the end was just the camera on a rope being winched up into the ceiling. The romance of making that, plus all the difficulty and drama, was epic. So, I went from Strictly Ballroom to this epic cinematic creative adventure.

It’s ironic to me that a lot of commentators called it “MTV Shakespeare”. I don’t mind, but MTV had nothing to do with it. I’ve never made an MTV thing in my life. What I was coming at was the way Shakespeare would do high and low comedy to disarm you. He would then slash that by flipping to high tragedy. I’m alright with it, but people back in the day would just say, “It’s bonkers.” But it’s prevailed, and it’s prevailed because there’s a method and process to the madness, if that makes sense.

I can give you an example: if you look at Romeo + Juliet, you’ll see there’s no actual objects in there that date it. At some point we were going to maybe have rollerblades and a Sony Walkman, but I knew that would date it. The cars are not dateable, the clothes are not dateable. That’s why it’s so profoundly copied. Even now, 25 years later, it’s still copied in fashion because it has its own world. But even in Strictly Ballroom, you can’t exactly tell if it’s the ’80s or the early ’90s. It’s slightly timeless. I build my films to move through time and geography, and mostly I build them for the future.

Moulin Rouge! (2001)

In 1899, a young English composer becomes infatuated with a beautiful cabaret singer at the famous Parisian nightclub.

If I was being honest with myself now, if I was self-examining — which is something I’ve often avoided doing, for good reasons — I’d say that yes, the cinematic ambition definitely did grow with Moulin Rouge!. I perhaps instinctively thought that to crack the code of the modern musical was too much of a leap after Strictly Ballroom. But to look at the modern language for Shakespeare? Achievable.

But then I went back to it. If you dig into the history of musicals, you see they have a language specific to their time and place. So, in the ’30s, something like Top Hat is so artificial that Fred and Ginger just say, “Let’s go to Venice,” and Venice is clearly drapes, a glass floor, plastic gondolas and the orchestra just bursts out of nowhere. When you get to the ’60s you get The Sound of Music, and it’s slightly more realistic: Julie Andrews is at least outdoors on a hilltop, and there’s a whiff of Nazis in it. You get to the ’70s, and that’s a much more realist period. They’re doing ironic takes, like Grease, on how musicals were done in the ’50s, or there’s Cabaret, where we’ve got a Greek chorus commenting on musical numbers that are done on stage, and this time the Nazis are actually terrifying. Each period has a way of connecting the audience to a set of rules that make a musical, and that’s what I was looking for with Moulin Rouge!.

George Lucas has always been so supportive. We were talking the other day about “immaculate reality”, the idea that if you create worlds, or a cinema language that’s all your own, then immaculate reality means that the rules within that world — your rules — have to be totally worked out. Even if the audience can’t pick up on them, you have to totally know them and stick to them so they’re able to buy into the world you’ve created. The mechanics in the beginning of Moulin Rouge! are meant to challenge the audience to sign on with that immaculate reality. After that, it’s meant to assault you through sound and humor and rhythm so that you surrender your intellect and hopefully feel, by the end, that your intellect has a response that lingers. But your emotional response is the first thing we’re trying to shake you down on. Guillermo del Toro said a great thing. He said it’s like a heist. It’s like a heist on your emotions.

Certainly Moulin Rouge! defied a lot of odds. Before we finished it, SNL heard there was this period musical that had ’70s numbers in it, so they did a send-up with Will Ferrell in a 19th-century costume proclaiming, “Everybody… was … KUNG FU FIGHTING!” It was hilarious! You can’t believe now just how preposterous the idea of the musical being reinvented was and how crazy it seemed what we were doing. Yet there’s no doubt about it, it caused a lot of controversy. I mean, Romeo + Juliet did cause a bit, but the feeling there was, “It’s all pop.” I remember the opening night in Cannes. I was with Francis Ford Coppola when the reviews came in from Time magazine’s critics: Richard Corliss’s said, “It’s the best film of the year,” and then Richard Schickel’s came in and said, “It’s the worst film of the year.” That kind of controversy just fueled it.

In the end a lot of people saw it. But everyone forgets that the international rollout of Moulin Rouge! happened during 9/11. Just recently a father brought two young girls to meet me, they were twins, and they were in their 20s. They were staring at me really intensely. They were French, and I thought, “Maybe they don’t understand what I’m saying.” Afterwards, the father — who was a cinephile, actually — said, “You don’t understand. When 9/11 happened, they were eight years old. They watched Moulin Rouge! every day. They were upset, but they hid in Moulin Rouge!.” They’re filmmakers themselves now, by the way. But there seems to be a pattern. I’ve noticed a whole generation of people in their 20s that Moulin Rouge! became a kind of refuge for.

Australia (2008)

On the eve of the Second World War, a British noblewoman inherits a huge cattle station in northern Australia and then must fight to protect it.

I do a whole lot of other things in between films, because I’m always looking for creative adventure. When you do one of these movies, they take forever, and I live them. I absolutely live the movies. The research takes years, and creating them takes years, so I want to make sure it’s something that’s going to keep me getting up every day. After Moulin Rouge! I started to get such noise, like, “This is his brand, this guy makes this kind of movie.” Now, I’ve always admired artists like David Bowie, or Picasso, or Dylan when he went electric. They flip what the audience wants from them, and they flip it because they have another note on their instrument that they want to explore.

For a while I was doing Alexander the Great, and it was a giant journey. I was so down the road on that. It was with Leonardo DiCaprio again, and Mel Gibson, and I was working with Dino De Laurentiis. At one stage Martin Scorsese was involved, and we built studios in Morocco. It was such an adventure, but there came a time when, for personal reasons, I really couldn’t continue with it.

So, instead, I did Australia. I wanted to sort of flip — if you like, in a postmodern way — Gone with the Wind and use it as a sweeping pastoral epic. But I also wanted to address, very deeply, the personal issue of the stolen generation in Australia. I always felt that this was something that only so-called “serious films” had been made about. Small films. But how do you take such a difficult subject in a way that reaches a broader and wider audience? That was my real motivation. Taking a traditional, old-fashioned form, the sweeping epic, and flipping the perspective to that of the indigenous child.

I was really living it, living in north Australia and working with some of our country’s great writers, like Richard Flanagan, learning about the stolen generation. As a filmmaking experience, it was by far the most fraught. We were hit by equine flu. I went to the desert to shoot, and it rained for the first time in 150 years, so I had a grass-covered desert. It nearly killed me, but I wouldn’t give a day of it up at all. Looking at it now, it’s probably the only thing I’ve done where there’s no confetti or fireworks. Actually, there might be, but if there’s no fireworks, there’s definitely a big rainstorm.

It’s weird because in America it didn’t play at all. It’s the only film I’ve had that didn’t really open in America. Everything else has played there, but it’s the biggest film I’ve ever had in Europe, and it still is. It’s still my number one movie in France and Spain, and I’m still not sure why. I was in Paris a couple days ago. They really lean into Australia, and they talk about it like it’s this masterful epic. I’m like, “Hey, isn’t it the loathed child?” But it’s the number two highest grossing Australian film of all time, so somebody saw it.

The Great Gatsby (2013)

An adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel about a Long Island banker who becomes involved with his enigmatic, party-throwing millionaire neighbor.

After these large films, I go on what I call a methadone program, because I’m so high on adrenaline that I allow myself a period of time where I’m sort of debriefing myself. I usually go off on my own for a couple of weeks, and after Moulin Rouge!, I went on the Trans-Siberian Express. Which, by the way, is not the Orient Express. Don’t get confused, this was not some beautiful first-class place where they bring you breakfast on a silver tray, it was a rattly tin box where a babushka would take a rubber hose, hand it to you and say, “Go shower!”

I had this new invention called the iPod. It had two speakers and on it were two recorded books. I don’t remember what the other was, but one was The Great Gatsby. I got out the red wine and I put it on. By the morning I was so enraptured in that world that I wanted to live in it. I started to pursue the rights, and I did Australia in between because it took that long to find a way of getting them.

Then there was the 2008 economic crash. It came after the Australia shoot, just as it does at the end of Gatsby: there’s the Roaring ’20s and then there’s the Great Depression. I thought, “Wow, this story speaks to now.” Which, I have to say, is always a crucial deciding factor in any work I make: can it speak to where we are?

Today, more than even when it opened, it’s got not just a fanbase, but teachers come up to me and say, “We show your Gatsby because young audiences understand not just what that time was like,” — and this is what I set out to do — ” but what it might have felt like.” I mean, it may be a quiet narrative, but it’s about the Roaring ’20s, by a brash, young novelist who was living in that crazy, far-out age. If you look at footage from the ’20s, they weren’t all dressed in white. It was noisy, it was colorful, and it was in your face. I mean, Fitzgerald put what was considered at the time to be a confronting kind of black street music called jazz into the novel, so Jay-Z and I decided to turn that into hip-hop. It caused a lot of dissension, but we did it, and it worked.

How I feel about it is how I feel about all the movies: they’re my children. Some are loved more at birth than others. Some are loathed by commentators, but they’ve all gone on to have relationships — mature relationships — with long-standing audiences. In the end, I made a choice a long time ago. If you’re going to make things that are very personal or out of the box, there’s only one relationship that really counts, and that’s the relationship with the audience and with yourself.

Best of Deadline

2022-23 Awards Season Calendar - Dates For The Oscars, Golden Globes, Guilds & More

Red Sea International Film Festival 2022: Best Of The Red Carpet Gallery

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.