Baseball’s stolen legacy: The fascinating story of the Negro Leagues and the man keeping the history alive

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

KANSAS CITY, Mo. – It was a normal weekday in 1993 when Bob Kendrick went to work, which on this occasion meant traveling to the third floor of the Lincoln Building at the corner of 18th and Vine here, the city’s historic hub of jazz, Black business and baseball.

He arrived at a modest, one-room office. A few pictures featuring Black faces, bats and gloves lined the walls.

Kendrick asked the only person there for the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

“Son, you’re standing in it,” the late Don Motley, one of the museum’s founding members and longtime executive director, told him.

This series explores the unseen, unheard, lost and forgotten stories of America’s people of color.

Then a 31-year-old senior copywriter for the Kansas City Star, Kendrick spotlighted local nonprofit groups that received free advertising space from the newspaper. The museum, four years away from opening in its current location across the street, wanted to promote its first traveling exhibition. Kendrick didn’t even know the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum existed – or that it had been founded in 1990.

He soon met one of the men in those pictures, John “Buck” O’Neil, as much a Kansas City institution as barbecue, one of the museum’s founders and a star player with the Kansas City Monarchs in the heyday of the Negro Leagues. O'Neil knew Satchel Paige and Jackie Robinson and developed a reputation as one of the greatest storytellers of our time. Kendrick became enamored with the tales of forgotten Black stars at a time when men -- and a few women -- would play, then be forced to travel miles upon miles for a hot meal and a bed that night at a place that would accommodate Black people.

The museum assignment ended, but Kendrick wanted to stay on O’Neil’s team. So he joined it, first as a volunteer at the museum, then on the board, then as the marketing director and, for the past 10 years, the president.

“Once you’re bitten by the Buck bug,” Kendrick said, “oh, man, it’s a wrap.”

The grandson of slaves and the first Black coach in Major League Baseball with the Chicago Cubs, O’Neil -- up until his death on Oct. 6, 2006, a month before his 95th birthday – was the unofficial Black baseball historian.

“I learned the stories. I didn’t live the stories,” Kendrick said. “But I think having watched him and his interactions with our guests, and I walked on so many of those tours with him, it’s opened me up to wanting to do the same thing.”

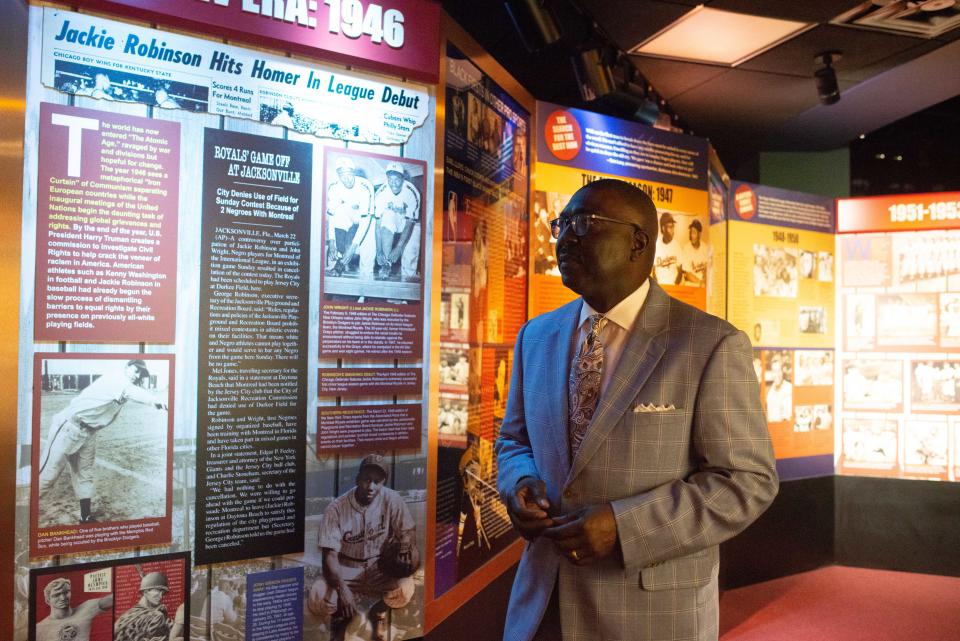

During his presidency, Kendrick has forged a new chapter for the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum that led to Major League Baseball, in an announcement last December, recognizing the feats, statistics and accomplishments of yesteryear. Without this museum and the proper acknowledgment, the history of baseball is incomplete. And without Kendrick, there’s a chance the baseball world wouldn’t have arrived at this reckoning point.

“Every American should engage the history of Black baseball to understand the long story of the way baseball was seen as a point of entry into an integrated American life,” said Adrian Burgos, a University of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign professor who studies sports history.

And as both America and baseball confront their history regarding race, the museum becomes a beacon.

“This museum is a civil rights museum. It is a social justice museum. It’s just seen through the lens of baseball,” Kendrick said.

For Kendrick, the story of the Negro Leagues is the quintessential American success story. He said that story has never been more relevant than it is today as the nation picks at the painful scars of the past.

“You won’t let me play? I’ll go create my own. That,” he said, “is such the American spirit.”

That spirit also drove Kendrick from humble beginnings in rural Georgia to the Midwest and a life as this history’s keeper.

A segregated pastime

Baseball is often referred to as “America’s Pastime,” which makes its period of racial exclusion particularly American.

Developed in the aftermath of the Civil War, baseball included mixed rosters with Black, Latino and white people on military, college and even company teams across the mid-Atlantic and Northeast regions. Jim Crow laws ushered in the whites-only era in which MLB began.

This series: The full history of American people of color has never been told. A new USA TODAY project aims to fill in the gaps

The “Negro Leagues” can trace its roots back to three independent Black teams joining to form the “Cuban Giants” – they picked up the nickname because they toured in Cuba in 1885. The Giants spawned teams that operated without an official structure until Rube Foster, the owner of the Chicago American Giants, called a meeting in 1920 at the Kansas City YMCA, a brick building still standing on The Paseo, around the corner from the museum. Today, the left exterior of the building features murals dedicated to O’Neil and the Monarchs, and it is the future site of the Buck O’Neil Education and Research Center.

Foster and other Midwest owners formed the Negro National League, the first organized league that existed in variations until about 1960 (historians argue about the exact year) in cities from Birmingham, Alabama, to Pittsburgh to Newark, New Jersey.

Many people know the story of Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947 – part of what catalyzed the civil rights movement – and know his professional career started with the Kansas City Monarchs alongside the legendary pitcher Satchel Paige. Some people know that Hank Aaron, the onetime home run king, played for three months with the Indianapolis Clowns. Yet only the most fervent baseball historian is familiar with the legendary speed of James “Cool Papa” Bell – said to be so fast that he could turn off a light and be in bed before the room got dark.

They probably don’t know Charles “Bullet” Rogan was a two-way star –pitching and hitting – during the same time period as Babe Ruth or that Baseball Hall of Famer and center fielder Oscar Charleston should be considered a top five player of all time. There is the little-known fact that Latinos who could not pass as white, and even those who could, started in the Negro Leagues. So did major league legends like Minnie Miñoso, a 13-time All-Star from Cuba who played with the New York Cubans and eventually with the Chicago White Sox, and Martín Dihigo, a fellow Cuban who never made it to the majors but was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977 by the Negro League Committee.

Three women played in the Negro Leagues: Mamie "Peanut" Johnson, Connie Morgan and Toni Stone. The first woman inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, Effa Manley, owned the Newark Eagles.

“The majority of us went through our own formal educations without knowing one of the most significant chapters, not just in baseball history but in American history,” Kendrick said, “and that is the history of the Negro Leagues.”

Opinion: Toni Stone, Connie Morgan and Mamie Johnson are the Negro League stars you need to know about

Opinion: MLB gesture to Negro League players is honorable but now it's time to pay them

Kendrick estimates there are more than 100 living Negro Leaguers who played well after the integration of the majors in the late 1950s. One of those players, Pedro Sierra – a right-handed pitcher from Cuba who joined the Clowns two seasons after Aaron – said the number is closer to 30.

Regardless of how many are left, the day none remains approaches, making people like Kendrick essential.

“We used to call Buck the voice of the Negro Leagues,” Sierra, 83, said. “Bob has kind of taken his place. So I call him the echo.”

Following in the steps of a legend

Thanks to some late-life fame gained through Ken Burns’ iconic nine-part (one for every inning) documentary “Baseball” in 1994, the modern baseball fan became acquainted with Buck O’Neil.

“He brought these individuals, these stories that he talked about,” Kendrick said, “he brought them to life.”

Kendrick likes to say O’Neil had newfound celebrity status as a result of his compelling narration of the Negro Leagues portion of the documentary.

“America fell in love with Buck O’Neil,” Kendrick said. “It literally set off a new career for him.”

O’Neil would enjoy that fame for 12 more years, which he spent gallivanting around the U.S. preaching the gospel of the Negro Leagues and the virtues of his new museum to anyone willing to listen.

“Guess who was along for the ride? Old Bob,” Kendrick said with his trademark laugh.

Three months prior to O'Neil's passing in 2006, Congress distinguished the museum as “America’s National Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.”

More: ‘Soul of the Underground Railroad’: David Ruggles, the man who rescued Frederick Douglass

O’Neil became more than a friend to Kendrick, despite the five-decade age difference between the two men. He was a mentor, a confidante. The baseball stories brought them together, but the shared time – traveling, at the museum, or on the golf course – bonded them.

“It didn’t matter how many times he had told a story. But if he’s telling it to you, he was going to tell it like the first time he ever told that story. He wasn’t gonna cheat you,” Kendrick said.

One of Kendrick’s favorite stories to tell centers on the time O’Neil hit for the cycle – single, double, triple, home run in the same game – on Easter Sunday 1943. As he had a celebratory dinner in a Memphis, Tennessee, hotel lobby that evening, O’Neil approached the first woman he saw. Ora Lee Owen was O’Neil’s wife for 51 years until she died in 1997.

Sometimes, as O’Neil regaled him with another story from the first half of the 20th century, Kendrick would think he was on the receiving end so he could one day serve as the conduit to the past, to the stories that make the Negro Leagues so important.

“I honestly believe that he guides my footsteps,” he said, “that he really is kind of this angel looking over my shoulder.”

Before the cross-country road-tripping, during one of their first chats, Kendrick asked O’Neil why the museum was important. O’Neil answered succinctly:

“So that we would be remembered.”

These days, he shares O'Neil's stories with pride, hoping museumgoers will say, "'Oh, Bob didn’t cheat us.’ He gave us every ounce of energy that he had,” Kendrick said.

Kendrick’s own story of humble beginnings starts in Crawfordville, Georgia. He’s quick to inform that the town of 500 is 80 miles east of Atlanta, 50 miles west of Augusta. He has fond memories of watching his mother churn fresh ice cream during this “carefree environment" growing up as the youngest of six boys.

“I didn’t know I was poor until I got to college,” he said.

Around age 11 or 12, his family installed indoor plumbing. “We had everything we needed,” he said.

Attending Howard University in Washington, D.C., had been his plan, but a partial basketball scholarship brought him to Park College in Parkville, Missouri (now Park University), in the fall of 1980.

“In the information they sent me they made it seem like it was really close to Kansas City,” he said with a laugh.

Parkville is 11 miles from the museum, and Kendrick never left the area once he arrived.

He bought a winter jacket for the first time and played on the school’s team for two years. The 3-point line hadn’t been adopted in the collegiate ranks yet, and Kendrick jokes that maybe his career would have been prolonged if it had been around.

A broken foot at the start of his junior season prompted him to focus solely on his studies, and he earned a communications degree in 1985.

For his first job out of college, in the composing room of the Star, he donned a denim-blue apron. Equipped with an X-Acto knife, Kendrick would receive editors’ hand-drawn layouts of the pages. He cut the type, pasted it and created the pages that ultimately became the plates for that edition of the newspaper’s printing presses. The job taught him about pressure and deadlines. He joined the paper’s promotions group, which operated as the Star’s in-house advertising agency, two years later.

As a copywriter, he led the advertising efforts for space donated by the paper to nonprofit groups. And in 1993, he drew the assignment of popularizing a museum about Black baseball players that opened on 18th and Vine.

‘No one gave it any chance of succeeding’

When the Monarchs played at Municipal Stadium, not far from where the museum now sits, businesses thrived, and the jazz of Charlie Parker and Count Basie played inside clubs like Street’s Blue Room.

“It was the epicenter for Black life in Kansas City,” he said. “Wherever you had successful Black baseball, you typically had thriving Black economies. 18th and Vine was no exception.”

But when Kendrick arrived at the cross street nearly three decades ago, the neighborhood “had been left to die,” he said. Vacant storefronts and half-caved-in buildings took up whole blocks. O’Neil and other ex-Negro Leaguers took turns paying the rent to keep the space.

“No one gave it any chance of succeeding,” Kendrick said.

Twenty-eight years later, Kendrick is the one leading the museum – in a much different form than the one-room venture it started out as across the street from the current edifice.

On this scalding, sweaty August afternoon, too toasty for his customary suit, Kendrick is as cool as a tall glass of iced tea in a crisp cream-colored short-sleeve button-down shirt, white pants and light brown shoes.

Some of the unopened boxes that fill his office, he said, are from when he moved in. The constant deluge of memorabilia only adds to the clutter.

On any given day, visitors could be roaming the museum’s corridors and suddenly hear Kendrick’s voice. For those who don’t recognize him, he keeps his identity secret until the end of the tour. Sometimes he’ll point out the T-shirt in the gift shop with a caricature of himself and the words “Chief Storytelling Officer.” That’s becoming harder these days, between his social media presence and the growing popularity of the museum.

“Buck was the greatest storyteller of all time,” said Jessie Murphy, the museum’s operations manager. “Mr. Kendrick is right up there with him.”

Kendrick worked his way into the presidency after years behind the scenes on the board. He spent 13 months away from the museum as the director of the National Sports Center for the Disabled before being asked to return in 2011, this time as president. He was inducted into the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame in 2014.

“Bob is a good-hearted person,” Murphy said. “He has created many avenues for this museum. In fact, when we were going down, he picked it up and it’s been rising up ever since.”

A 100-year birthday celebration for the late O’Neil marked Kendrick's first year back. Kansas City hosted the 2012 All-Star Game, bringing the spotlight to the city, and the Royals’ success in 2014 and ’15 kept it there, helping the museum flourish with an influx of visitors. In between, Kendrick hosted a Hollywood-style “42” premiere with Chadwick Boseman, who played Robinson, and Harrison Ford conducted media interviews on the release date from the museum’s famous “Field of Legends.”

“I’m not saying this just because he’s here,” said Cathie Moss, the museum’s event coordinator and occasional tour guide herself. “I don’t think this museum would be on the same level or footing it is today had (Kendrick) not come back when he did.”

The museum has been profitable for years and is on solid financial footing now – a $20 million turnaround for the organization, Kendrick said. Tax records confirmed this.

Kendrick and curator Raymond Doswell, who is responsible for the museum’s layout and content, helped museum attendance grow year-over-year “exponentially.” They hoped to attract 100,000 visitors in 2020 before the pandemic hit. More than 2 million visitors have passed through the glass doors since the museum building opened in 1997.

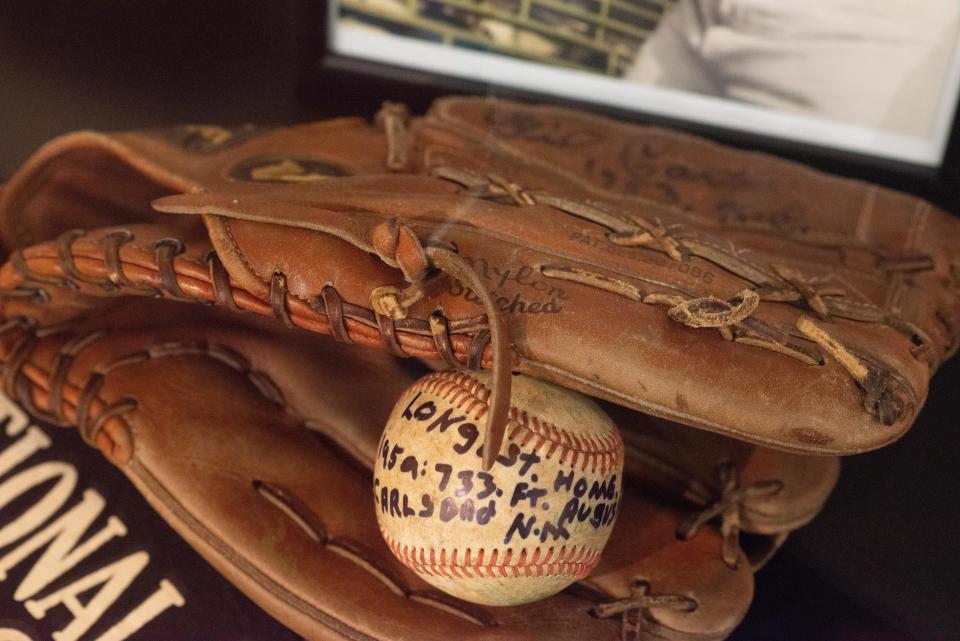

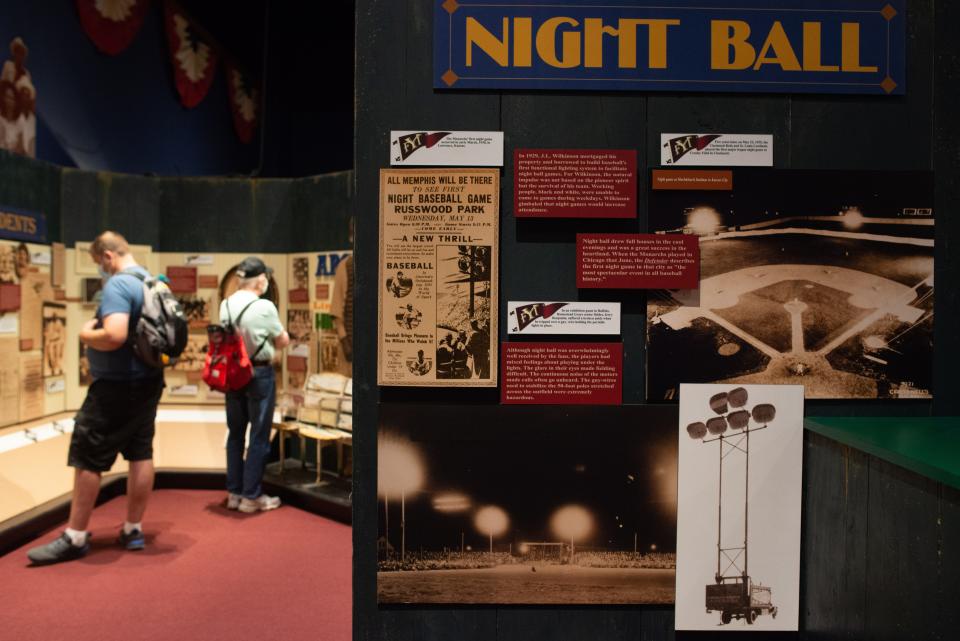

The 10,000-square-foot space houses decades worth of baseball artifacts. Photos with insightful descriptions line the walls, walking visitors through a timeline of Negro Leagues history in a quiet atmosphere – unless Kendrick’s voice is booming during another impromptu tour. Thirteen life-size, bronze statues situated around a baseball diamond make up the Field of Legends, the final stop of the tour.

“Breaking Barriers,” the seventh traveling exhibit, will debut next year in conjunction with the 75th anniversary of Robinson’s feat and honors the player to break each organization’s color barrier until 1959.

One year and one day after the museum closed for three months because of the pandemic, a vaccination site opened on the premises – an example of the public service function the museum carries, Kendrick said.

“We still operate in the heart of an African American community, and a lot of people who live in this community are underserved,” Kendrick said.

Through a partnership with MLB’s Kansas City Royals and the local Boys & Girls Club, a state-of-the-art baseball complex sits one block behind the museum.

The focus, however, remains on the baseball players from decades ago.

“Through Bob’s storytelling and his gregarious personality and Raymond’s commitment to staying true to the story and telling it and sharing it through the collection, through the exhibits, through the communities, you really see the best of the Negro Leagues,” said Burgos, the Illinois professor who wrote “Cuban Star: How One Negro League Owner Changed the Face of Baseball,” about the Afro-Cuban-American Alejandro “Alex” Pompez.

Keeper of the legends

The museum allowed Kendrick to meet his baseball hero: Aaron.

Kendrick recalls being 12 and running around his parents' living room in joy the April night Aaron broke Ruth’s home run record in 1974. Taking Aaron on a tour of the museum will always be the highlight of his career.

“(He’s) the only person I’ve ever been star-struck around,” Kendrick said.

His tour with Aaron ended with them and Aaron’s wife, Billye Aaron, sitting around a plate of ribs doused in original sauce at the revered local food joint Gates BBQ. The couple jokingly asked Kendrick if he had any ribs on him every time they saw each other until Aaron’s death in January.

“Memories mean a whole lot to me,” Kendrick said. “This museum is filled with memories.”

Memories also fueled one of Kendrick’s latest ideas, “My Baseball Memory,” which launched Oct. 6 – the 15-year anniversary of O’Neil’s death. Former Black MLB players Frank White and Joe Carter sat on a panel to help launch the campaign, designed to raise Alzheimer’s awareness in the Black community. Fans were encouraged to share their most-cherished memories related to baseball on social media accompanied by the hashtag #MyBaseballMemory.

Kendrick has jumped headfirst into the challenge of making the museum relevant for both younger and older generations, including those who use a variety of online platforms. His 20-episode podcast series, “Black Diamonds,” includes conversations about Negro Leagues stars and teams with historians and other baseball luminaries.

He might be prone to retweeting mostly everything he’s tagged in, but his Twitter account also supplies his 45,000 followers timelines with facts, figures and stories of the Negro Leagues and their legends. He sees it all as a tool to connect the museum with the younger generation, who will one day become responsible for financially supporting the 501(c)3 nonprofit.

When the coronavirus pandemic dashed the grand plans to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Foster’s creation of the Negro Leagues that Kendrick had coordinated with Major League Baseball for 2020, he adjusted. The “Tip Your Cap” campaign was born, and it kicked off with four living U.S. presidents – Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama – giving their support to the museum with short video messages and literally tipping their baseball caps on social media to honor the men and women who were denied the chance to play in the majors.

“My Baseball Memory” and “Tip Your Cap” are examples of ideas that Kendrick wakes up with in the middle of the night. He jots them down immediately. The museum is never far from his mind.

Like a baseball manager, Kendrick feels he receives too much credit for the museum’s success. He, obviously, hands it all to his old friend.

“I talk to Buck almost every day. There’s not a single day that I don’t talk to Buck. He don’t always talk back to me,” Kendrick said. “It just seems like everything we try to do, it seems to work. And I ain’t that smart.”

In previous generations, Burgos – the Illinois professor – argued it was men like Kendrick and Doswell who would have been Negro Leagues leaders, either guiding or owning teams or chronicling it like famous Black journalist Wendell Smith, who followed Robinson in 1946 and 1947.

“This is why so many of us love Buck O’Neil,” Burgos said. “Because he was the legacy. And these men are carrying that legacy forward.”

Kendrick’s goal is to leave the museum on more stable ground compared with when he returned. Improving life for those who come next is a duty of the human condition, he reasons.

“One day, my granddaughter will bring her children here and say ‘your great-grandfather had a hand in this,’” Kendrick said. “None of us are going to get rich doing this.”

They are rich in so many other ways, Kendrick said.

Rich in memories. Rich in passion. Powered by the stories of those who are enshrined here and the people who have made that mission of remembrance – and equality – their life’s work.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Beyond Hank Aaron: Negro Leagues Museum houses stolen baseball legacy