‘Bardo’s Alejandro G. Iñárritu On Capturing Personal Dream On Film: “I Don’t Know If I Am Interested In Going Back After This Just To Tell A Story”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

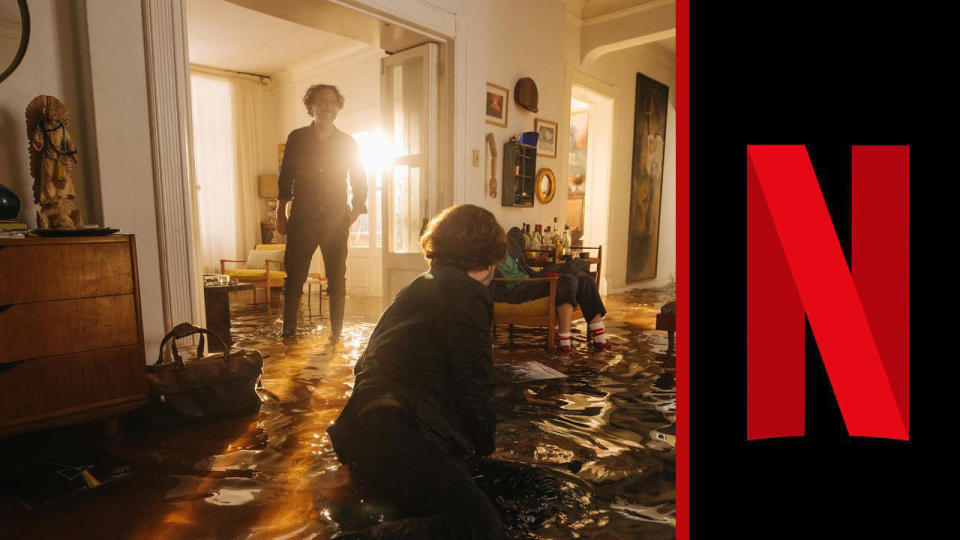

EXCLUSIVE: When he comes to a film festival with his latest film, Alejandro G. Iñárritu cuts a supremely confident swath. As he premiered his film Bardo in Venice, the writer-director seemed a bit more vulnerable. This is understandable because the film is a mix of dream and reality, a deep dive into his own life tragedies, the identity conflict facing an immigrant who becomes wildly successful in their adopted country, and the inevitable need to face one’s mortality.

Pair that with the filmmaker’s wild visual imagination, and you’ve got an auteur tour de force. Wait until you see how Iñárritu visualizes the loss and grieving of an infant, for example. Here is a brief conversation with the filmmaker on why this film, his first for Netflix, was a harder undertaking than The Revenant, which put Iñárritu and his star Leonardo DiCaprio on long sabbaticals just to recover from that grueling, frozen undertaking. And which won Iñárritu his second consecutive Best Director Oscar, and DiCaprio his first for Best Actor.

More from Deadline

Alejandro G Iñárritu's 'Bardo' Met With Warm Reception At Venice Premiere

'Bones And All' Premiere Gets 10-Minute Standing Ovation At Premiere - Venice

Venice Review: Alejandro G Iñárritu’s ‘Bardo’

DEADLINE: I recall you attempted to return to filmmaking after The Revenant with a big-ticket ambitious project that dealt with global warming, possibly with Leonardo DiCaprio. I recall the budget for what you wanted to do getting in the way. Did that prompt a fallback to Bardo?

IÑÁRRITU: It is a very ambitious project, and was complicated financially. It was a film that was completely different from this. When that one came down, I felt the clock ticking, the need to look inside, instead of looking outward. Maybe it has to do with the fact I am turning 60 next year. When you are closer to death, you start thinking that maybe it is worth exploring the journey [you’ve been on]. It’s very elusive, very labyrinthian, about trying to make sense of things in some way. With no other interest beyond whether it was truthful for me, emotionally. The things that happened since September of 2001 when I left Mexico to move my family to the United States has a lot to do with this film. Without that, I would not have made this. It is about the toll that it took to make that decision, on me and my kids and my wife and my life. And it was about my age. Those were good starting points, the most significant foundations that allowed me this opportunity.

DEADLINE: When you make such a personal film informed by the events of your life, how did you feel at the end, compared to when you finished The Revenant?

Netflix

IÑÁRRITU: This movie is much more complex than The Revenant. The Revenant is a genre, with a structure and a plot and an ending. This one was a dream, and logic does not have any place in dreams. Like a dream, cinema is a lie, or at least it’s not true, but a dream is very meaningful, as is cinema and it can change your life. There is a line that film is a dream, being directed. For me, this film was me, building a dream that was personal, meaningful, super complicated technically, incredibly controlled. I needed that because when you try to relate your dream, you remember the details and they have important meaning and have to be precise. In order to be in that space, I had to really control every aspect. This film was more complicated than The Revenant in many aspects, including no structure, no genre or books to follow. This was much more satisfying. It was like catching air, I didn’t know how to do that, and I never made a film like this one before.

Venice Film Festival: Deadline’s Full Coverage

DEADLINE: After this, do you go back to that other film you couldn’t get done?

IÑÁRRITU: No, I don’t know when I’m going to touch a camera again. I’m a little burned out, I’d like to have some time off. I don’t think I can go back and do a movie with a beginning, middle and end, a plot. After making something about the mind and what it tells you…it was very satisfying. There were no rules and it wasn’t about how smart you are. It’s about how deep you can go, how honest you can be. At least now, I don’t know if I am interested in going back just to tell a story after this. I don’t care about story, or reality. I care about the interpretation of reality, that space between the event, and the imagination. There is a territory where cinema…the great masters taught us how to use that and we have forgotten about it. We rely on the narrative storytelling and it feels a bit the same. I think there are endless possibilities and I would be clueless if I don’t find another way to keep doing this.

DEADLINE: When you watch the film, it is easy to imagine Daniel Giménez Cachore’s journalist/filmmaker character as you. There is the loss of a child, reason to face mortality, insecurities and an ethnic identity conflict. Fair to imagine much of this came directly from events of your life, including the character’s argument with a customs agent who tells him that he and his family cannot call the United States “home,” that they come from someplace else?

IÑÁRRITU: That happened to me, exactly that way. For 15 years, I had an O1 Visa. I have to renovate that every six months. Once I had a reckless driving [thing] in 2003, and that was it. That reckless driving, every time I return to the United States, which has long been home for me, I was always ordered to secondary [screening]. Which was very annoying. Even the officers in the airport who knew me were obligated by law, they had to put me into this secondary [screening], which means you have to go into a room with a bunch of people who had other problems, and wait for 45 minutes or an hour for somebody to revise your papers. They say, we know this is bad, but it’s our system. I would say, why do you have an incredibly complex system to detect a reckless driving thing 15 years ago in another state? Why not just say, okay, this guy has paid his dues. Some of the officers were nice, others not. Many times, when I went to Tijuana to renovate my thing, and you’re at the border and my kids and I were in the car four hours in the heat. I went to the officers and said, I’ve got two kids burning up here, and he doesn’t even look you in the eyes. So I felt invisible, you are nothing. Even though I have a car, and I am somebody. I thought, how must other immigrants get treated? I had rough experiences with some officers, not all, some were very nice and human. But you found yourself, where home is what it says in a little paper, and you are never certain if you belong someplace. My wife, once she returned, had this same event, and she arrived home, crying. The same thing happened to me; a guy said, this is not your home. We have shared so many stories like that, but I loved that scene because it is what you feel when your identity relies on what is written on a paper, and it can be interpreted by anybody that has a bad breakfast. And you are invisible, you are nothing.

DEADLINE: The protagonist has a conversation with the Cortes about the bloody conquest of Mexico, and there is an early encounter with an emissary for the American president who wants the journalist to back a proposal for the sale of land in Mexico and California by Amazon. There is an incredible visualization of the death of Mateo, a child of the couple who died after only living a single day, that was based on your own personal tragedy. How do you feel after putting such personal things onscreen, like your own conflict about personal identity?

IÑÁRRITU: It was a long process, for me to write it down. I did this film not with my mind, but with my heart. On a very conscious and subconscious level. Things that have been on the surface all my life, and things that have been blocked maybe, by time and things that do not let them out but which still has a presence and consequence in your life. The perception of your feelings in your life. That was the dive in that I went for, looking for what was truthful, for me with emotional certainty. Memory does not possess truth, it just possesses emotional certainty. That is the truth I went for. During the preproduction and the shooting, it was a whole process that itself revealed things that gave me an opportunity to dive into painful memories, and at the same thing revive come-to-life-again, happy, humorous, silly memories. It was both.

In other dramas I have made, I always felt I was putting the audience into a very deep ocean, with the darkness and the waves, and the sharks. Maybe it is my age and perspective, I feel like this film is not a dive for the audience, but more like snorkeling. From the surface, you can see the depth, at the same time you can see the lights, the grays, the darks, a different way. It was that candor and that light that I wanted. You can’t talk about things about yourself without light and humor. All those things we lost as a family, brought out other things that are very prideful and meaningful. So it was a combination of these emotions, a process where a lot of things were revealed and were all the time transforming.

DEADLINE: You could feel the internal of identity in yourself through dream sequences of history in Mexico. As an artist who grew up and spent most of your life in Mexico, and then came to the United States how did the film help you feel at ease with your own identity?

IÑÁRRITU: This film has been very cathartic, and very liberating for me. Liberated from ghosts, and ideas and preconceptions. I feel that Mexico is not a country as much as a state of mind. In the U.S. and in every country, you have been told stories since you were a kid, narratives that build your sense of belonging, help you identify with people and give you power. If you go to another country for 20 years, say you are living in Iraq, those stories…you’ll have some distance and perspective to question them and resolve them. Resolving your own identity, your own stories of your life, of Mike Fleming’s life that you have built to build your identity and your story, that is created by you. All the events that have shaped your life has been interpreted by your nervous system, your system of beliefs, your religion, your language. When you see that narrative from a distance, you realize those narratives from your nation and from yourself are just…stories. They are maybe not true. They can be true emotionally, but if you see your brother at Christmas and tell a story, he will say, no it wasn’t like that, it was like this. Then you realize, for another person it was a completely different experience and point of view. Life is made of fragmented points of view and realities and that guy in the movie is looking for the truth. He’s in such a crisis. He knows his own narrative is not real, that his country’s mythological bullsh*t is not real, and what has been made of it to make sense…it’s like time, which is important, but we believe time exists and no, it’s a human mind invention. For me in revisiting all these things, I could liberate myself from ideas that before were certainties for me. It’s terrifying because you reach a certain age and things dissolve, and things become more elusive as time and space start to melt. This was liberating for me. It allowed me to question, and see things in a different way. That was the process, the liberation. It was terrifying to show this film, share this internal process. I’m very vulnerable. But I now have nothing to hide. I could not have made this film even five years ago. You have to be ready to see things in a different way, with a little distance and without reacting but rather responding to things.

Best of Deadline

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.