Their Band Ended in Tragedy. 20 Years Later, the Last Surviving Member Is Ready to Talk

July 19, 2003: It’s well after midnight in San Francisco, and the Exploding Hearts — Adam Cox, Terry Six, Matt Fitzgerald, and Jeremy Gage — are ready to play for a packed house at a bar called Thee Parkside. The show is a “last-minute thing,” Six, the band’s guitarist, remembers. They’d driven the 10 hours from Portland, Oregon, to play another local gig the night before, and when this spot opened up, they figured they’d stick around for one more. “I remember thinking, ‘We only have one fucking show,’” he says. “So we hop on the bill as headliners.”

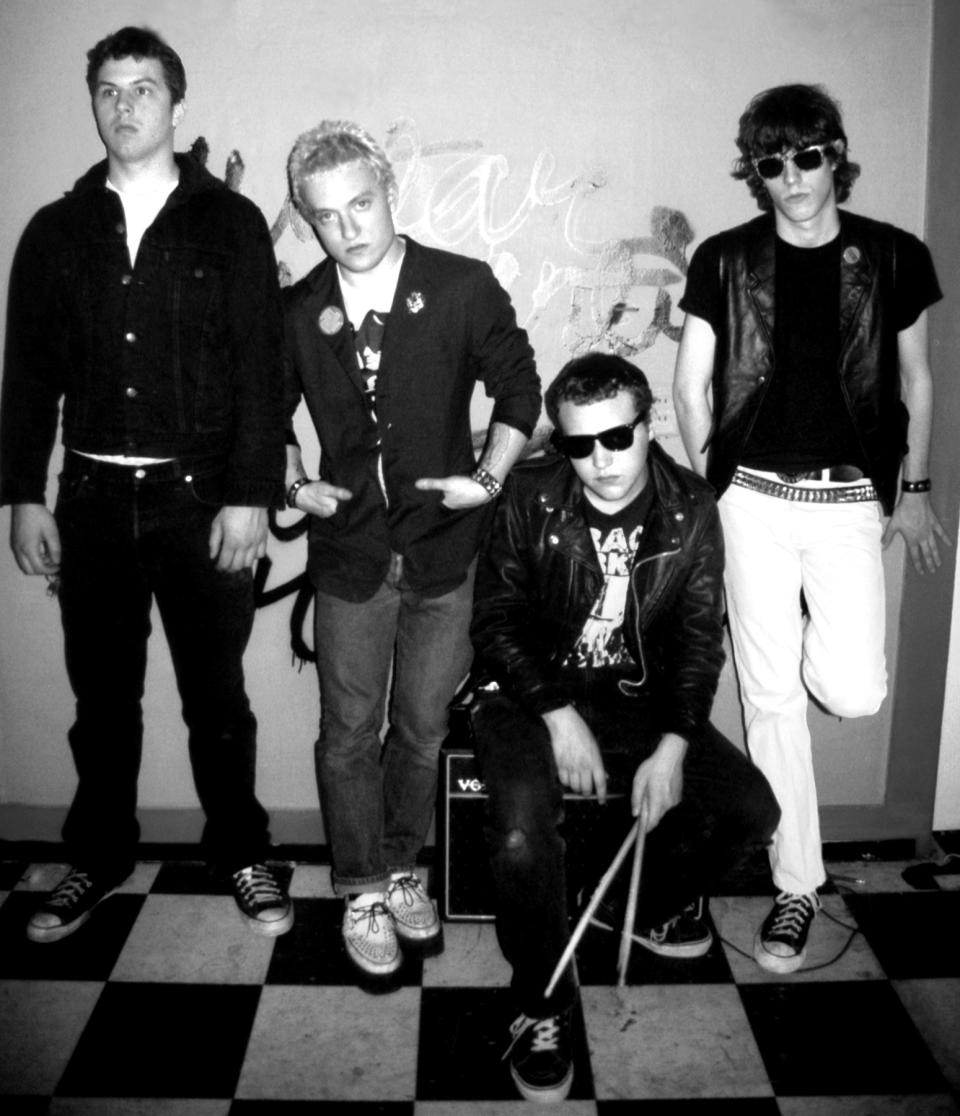

On their first night in town, the Hearts’ performance at the nearby Bottom of the Hill had been enough to solidify what they knew about their band: Major success was not an if. “It was when we were going to get traction,” Six says. Lookout Records — the punk label behind Operation Ivy and early Green Day — was there, and they were impressed. The band sounded good, with a snotty power-pop attack inspired equally by Elvis Costello, Nick Lowe, and the Nerves’ Paul Collins, plus a fair amount of Johnny Thunders. They looked good, too, all bleached-out Levi’s and acid-washed T-shirts in a DIY mix of black, white, yellow, and pink.

More from Rolling Stone

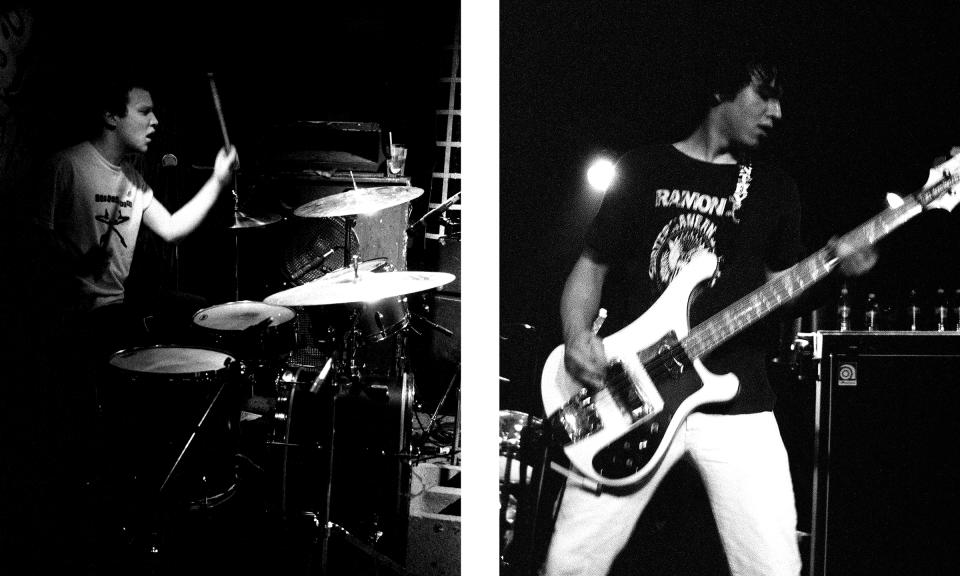

The crowd was singing along, which was surprising for a band that hadn’t had a chance to tour much. They’d played plenty of shows in Portland and Seattle, but it was in San Francisco that they realized just how much their debut album, Guitar Romantic, was catching on.

The Hearts didn’t go on at Parkside until the early hours of Saturday morning, around 1:45 a.m. — 15 minutes to curfew. “We were four songs [in], and they cut the power on us,” Six says. But the venue only cut the PA — not the stage — so the band kept going. “Everybody just kept screaming at us to play one more,” Six says.

July 20, 2023: Six is getting ready to play Guitar Romantic straight through, in its entirety. He’s bouncing around in the green room at TV Eye in New York City, stretching limbs and vocal cords that are decidedly not as flexible as they were two decades ago. The music hasn’t aged a day, though. It’s the soundtrack of snide teenage heartbreak, all angst and forlorn love, with clever lyrics (“I hung new posters on my wall/And the dog don’t remember your name”) set to riffs that can earworm their way into your brain for days. Those qualities have given Guitar Romantic a devoted following over the years, and it’s played so often in bars and clubs that it can sometimes feel like it’s following you. “I’ve heard so many stories from everybody about how this record changed their life, in every way imaginable,” Six says.

Six isn’t here with the rest of the band. They haven’t played a show together since that night in San Francisco, but he’s barely spent a day not thinking about them. That’s because, on their way back to Portland that Sunday, not long after dawn, their vehicle flipped on a quiet stretch of highway near Eugene, Oregon. Cox, the singer, and Gage, the drummer, were killed almost instantly. Fitzgerald, their bassist, succumbed to his injuries in the hospital hours later. In the blink of an eye, everything seemed to come to an end for the Exploding Hearts. But in the years since, the band’s legend has only grown.

Six has spent all those years seeing himself as the custodian of this band and its one classic album. But he’s ready to move on. To finally let go. To give Guitar Romantic back to the fans. And here, in a 250-capacity club in Ridgewood, Queens, New York, fog machine blasting into another packed room — 20 years to the day since he lost his best friends — he’s about to do just that.

“I CAN’T SPEAK to the people that get this record as a hand-me-down, but it always comes with a story, right? It always comes with this lore.” Six is in his home near Joshua Tree, California, sipping a coffee on a Wednesday morning in late June, his big, dark eyes staring into the Zoom camera. He worries that something about the Exploding Hearts’ only album has been hidden behind the tragedy of three premature deaths — Cox was just 23, Gage 21, Fitzgerald 20 — and the question of what could have been. “To me, that record is a representation of that time in our lives, where we were young and stupid, and we didn’t care. We just wanted to be in a rock & roll band and have fun with it,” Six says. “I always look [back] fondly — even the times when Adam and I would come to blows. It’s still the best part of my life that I ever had.”

That joy comes through in all 10 songs and 27 minutes of Guitar Romantic. Within weeks of its U.S. release in March 2003, it was getting attention. “It seemed like the buzz was getting deafening,” says Ken Cheppaikode, whose Seattle-based indie, Dirtnap Records, put out the album. “We were selling those CDs as fast as we could press them.”

Bigger labels were eying them, too. “They had this explosive energy,” says Chris Appelgren, who ran Lookout at the time. “They wrote great songs, referencing great power pop.” They remind him of Mick Jones’ songs for the Clash: “This kind of beautiful, fragile sincerity amidst all of this brash noise.” He compares the band to the Ramones, too. “They were completely unique, but at the same time, you can hear what their influences are, what they loved, in what they were doing.”

Cathy Bauer, Lookout’s general manager back then, went to both of the Exploding Hearts’ San Francisco shows that weekend. “I remember the amount of excitement that came from the crowd,” she says. “It’s not often that a band that has never toured can just walk into a room and get people dancing. They looked cool, their gear was cool — it was a really amazing first impression.”

Just hours later, the band’s narrative was changed, perhaps irreversibly. It’s a shadow that Six is ready to have lifted. “I think that 20 years is enough time to reshape that,” he says. The idea of the album being “tucked away” and not played — that on top of its exuberance, there will always be immense grief — weighs on him. “That’s not why we made this record,” he says. “We made it to be played extremely loud and shared with the world.”

Six worked with Third Man Records for a 20th-anniversary expanded rerelease of the album, which came out in May. He got a band together to “put the album on tour” — five dates only — so its most dedicated fans could hear it live. He’s telling his story to Rolling Stone, in his first in-depth media interview in years, possibly ever. He says he felt ambivalent about all of this, but then he thought of his friends.

“I just thought about it in terms of, what would Adam, Jeremy, or Matt do, if they were stuck here?” he says. “I would want them to go do it.”

AT ABOUT FIVE-FOOT-THREE, Adam Cox wasn’t tall, even with his creepers on. But he was an unmistakable presence, a romantic with a short fuse who took his look just as seriously as he took his music. He was the kind of bandmate who’d run around town to drop demos off at local record shops and post on message boards to talk up his group. He wore tight jeans he bleached white in the bathtub, and he changed his mind so often that by 23, he’d already had some of his tattoos covered up. “Adam had a lot of energy,” Cox’s friend and self-proclaimed Exploding Hearts “Number One fan” Jessica Sawyer tells Rolling Stone. “He always wanted to do something, or read something, or discover something.”

Growing up near San Diego and later in Portland, Cox was always interested in art — he took classes from a Dark Horse Comics artist at a local university — and was a talented writer. He began coming around to music, too, learning bass, guitar, drums, and anything else he could get his hands on. “He taught himself how to do the accordion,” Alma, his mother, says proudly.

Adam and his mom were particularly close, and even after high school, when they were living in separate cities, they would talk on the phone often about his life and ambitions. “He was very determined that he was going to have a band, because he didn’t want to play for anybody else,” she says. “That was my baby. He wanted to be the star.”

Cox had gone to an arts-focused high school in Beaverton, Oregon, called C.E. Mason — a magnet school for kids who had a hard time learning in traditional environments. “It basically turned into a school for fuck-ups and rejects,” says filmmaker Ardavon Fatehi, who went to school with the band and has been working on a documentary about them since about 2015. “We had a great set of teachers that were really nurturing to all the weirdos and freaks.” Countless bands sprung out of this community, and kids swapped in and out of their lineups.

“[Adam] was determined that he was going to have a band, because he didn’t want to play for anybody else. He wanted to be the star.”

For a while, Cox had a band with Six and Gage called the Iguanas, a garagey punk outfit that would practice in the basement of Cox’s apartment in Southeast Portland. Later, after Gage and Cox went on tour in Europe with a band called the Spider Babies, Cox decided he needed a break from Portland and went to stay with his folks in southern California.

Cox spent a couple of months there, taking singing lessons from a friend of Alma’s. He and Six kept in touch, too, playing songs to each other over the phone. “’Jailbird,’ ‘Modern Kicks,’ and ‘Still Crazy’ — those are the three that I was working on,” Six says. “That’s what perked his interest. And then he just called me and said that he was gonna figure out a way to come back.”

“Adam came back to Portland, and he had all these fucking hit songs,” Fatehi recalls. “He was ready to put his band together and take things to the next level. And we all kind of wondered how that happened. Like, what the fuck you doing down there? Who’d you meet?”

Turns out that Alma worked at a Wells Fargo branch where one of her clients was none other than Ike Turner. They had become friends, and one day she mentioned that her son was a musician, too. “He invited him to come to his home,” she says. “I took him, and they had a great time playing together. He taught him the positions on the guitar that he had taught the guitar player of the Rolling Stones.” (“He showed me the whole Keith Richards tuning thing,” Adam told Maximumrocknroll in 2003.) Fatehi sees Cox’s afternoon jam session with Turner as a foundational meeting. “This is a Robert Johnson crossroad situation,” he says.

Six and Cox persuaded Gage to play drums; on bass was a guy named Jim Evans, a 41-year-old musician who brought a slow, steady pacing to the band’s sound. In 2001, a few months after Six graduated high school, they played their first real show, at Satyricon, a long-running punk venue that had been a home for Pacific Northwest acts like Poison Idea and Nirvana. Roughly seven people showed up.

Sometime that December, Cox met King Louie Bankston, a New Orleans garage mainstay who often spent time in Portland. Bankston spotted Cox skating one day, and, familiar with his other band, shouted “Spider Baby!” They got to chatting over a few drinks, and Cox gave him the “Pink Demos,” some low-fi recordings the Hearts had put together on CD-R. “Louie called him in the middle of the night, that same night, and said, ‘You have to let me in the band,’” Six recalls. “I have a song. It’s called ‘I’m a Pretender.’”

Bankston, then about 31, was a Ferris wheel operator at Portland’s oldest amusement park, and was often seen munching on a corn dog or a pickle in a bag. Six knew him from his band the Persuaders, and for the one-man-band act he performed around town. When he showed up at their house a few days later, Six says, “I didn’t really have any ceremonial chivalry. I just grabbed a guitar and gave it to him.” Bankston played what sounded like a skate-punk anthem. “I was like, yeah, OK,” Six says. “This is a really good fucking song.” (Louie loved to tell people another story about that song, which has worked its way into the band’s lore: “He played ‘I’m a Pretender’ for Alex Chilton, and Alex Chilton said, ‘Louie, this is a hit song. Save it for when it matters,’” Six says.)

Six calls “Pretender” Bankston’s “entry fee into the Exploding Hearts”; the New Orleans musician ended up with co-writing credits on seven out of the album’s 10 songs. “He was so loquacious with his phrasing,” Six says. “It was like a Henry Rollins poem.”

Outside the band, the boys spent their days at Burnside Skatepark or digging through record bins. “It was like a competition with each other, a giant treasure hunt,” Six says. They learned from each other, working backward through generations of bands. “Myself and Adam, we were listening to a lot of Nick Lowe, Rockpile, Elvis Costello, the Beat, Paul Collins, the Nerves,” Six says. “They were really fun to talk about music with,” says Colin Jarrell, a friend who played in various bands with Six and Cox. “They paid a lot more attention to how stuff was made than a lot of people.”

Six remembers how determined they were to break out of the “testosterone-fueled punk music” scene of the Pacific Northwest at that time — and how those around them didn’t necessarily get it. “There was a culture that didn’t like androgynous kids that put on makeup and sang about heartbreak. So we were immediately written off as a joke,” Six says. “Back in [those] days, the word ‘fag’ was used quite a bit. So we were fags.”

None of that slowed Cox down. “He was visionary,” Six says. The singer thought meticulously about everything from the show flyers he designed to the kind of clothes they wore onstage, sticking to a strict palette of day-glo pink and yellow. “We looked like psychopaths on the streets of Portland,” Six says. “In the early 2000s, it didn’t make any sense. We totally looked nuts.”

THOUGH MATT FITZGERALD was only 20, he had a brash confidence about him. “I’ve been 21 since I was 16,” he’d tell his younger sister, Molly, when he caught her sneaking into one of the Hearts’ first bar shows. Their dad was a computer engineer, and Fitzgerald inherited his way of thinking. “One time he read a book about how to build a car engine, and then he just drew it out to scale,” Molly says. “Like, no big deal.” He was known as Matt Gyver, a play on MacGyver. He owned a motor home that would sometimes break down, and Molly remembers the story of how he fixed the thing one time with a ballpoint pen. “His brain was some other level,” she says. He always had a hustle, too, like selling Walkman batteries or cut-rate candy bars in the halls of his middle school — for a reasonable markup, of course. “Very entrepreneurial,” Molly says.

Fitzgerald had also dealt with his share of tragedy. His freshman year of high school at C.E. Mason, Fitzgerald’s best friend, Chris, took his own life. It crushed Matt. He quit football, basketball, and baseball. “I think that’s when he decided, I want to do the things that matter to me,” Molly says. A couple of years later, he quit school altogether.

The Fitzgerald home had an open-door policy, and C.E. Mason kids would constantly be coming around. They had a drum kit, some amps, and a couple of microphones in the basement, and a kitchen table that became the site of intense teenage debate. “They would sit for hours with my parents and discuss society,” Molly says. “I was like, ‘Basketball practice!’ And they’re like, ‘We need to change the world!’” Gage would come by and play in bands, and Six would occasionally join for dinner, which became a regular event on Mondays in the wake of Chris’ death.

When Evans, the Hearts’ bassist, left the band just days before they were set to enter the studio, his replacement was an easy choice. “Matt walked in and everything was done, in terms of the songwriting,” Six remembers. But Fitzgerald’s punk style gave them an edge they’d been missing. “He played the bass like a guitar player, and he played very fast,” Six says. “I feel like that’s the reason why Guitar Romantic sounds the way it does, is because we’re relearning it as we’re going.”

They recorded the album relatively quickly in early April 2002. “We probably worked on it for about six or seven days over two weeks,” recalls engineer-producer Pat Kearns, whose Studio 13 was essentially an unfinished basement with some audio equipment. “We were on a roll for this sort of teenage snottiness.”

Ratch Aronica, Kearns’ fiancé and a professional band manager, saw real potential. She’d been watching acts like the White Stripes building full-fledged careers from well-crafted garage-pop songs, and she was sure she could help the Hearts do the same. “I really like what you’re doing,” she told them. “But bottom line is that you’re gonna have to listen to me.”

“I think that’s when [Matt] decided, I want to do the things that matter to me.”

For Bankston, this was the end of the road. He’d been a productive if sporadic member of the band — showing up to drop a one-liner lyric or to lay down a keyboard track, wandering out just as suddenly as he’d wandered in — but he wasn’t interested in pursuing that kind of career with them. “He saw the direction we were headed,” Six says. “He was like, ‘I just want to play roadhouses and do my thing.’ That was that.”

For the rest of 2002, they played regularly as a four-piece to growing audiences. Their chemistry as musicians was undeniable. “We didn’t really need to tell each other what to do for cues at that point,” says Six. “When we had an idea, Jeremy and Matt got it instantly.” Six had moved in with Cox and his beloved Boston terrier, Bluto, dubbing their place “Hell House” (others called it the “Pink Palace,” even before the spray-paint fight that left streaks of pink and yellow across their walls). It was a semi-furnished, poster-decorated “glorified tree fort,” where they could sit upstairs and write songs, or head to the basement and practice. There was occasional tension — like the time Cox felt that Six had upstaged him during a set (“We had it out that night when I got home,” Six recalls) — but in general, they were seeing eye to eye.

Aronica’s management was giving them the direction they needed, too. Some of them were still underage, but they had started playing regular bar gigs, even opening slots for buzz bands like the Kills. “These are shows that we never would take on our own accord,” says Six. “But Ratch was indignant, saying, ‘You need to start being a band.’ And she was right. We started getting attention.” For New Year’s Eve 2003, the Hearts opened up for the Makers, a Sub Pop act known for their flamboyant style. Looking into the faces in the crowd, Six felt for the first time like it all clicked. “Portland finally got it,” he says. “That room was completely electric.”

In October 2002, the Hearts had done a “spit and a handshake” deal with a German label called Screaming Apple to press Guitar Romantic on vinyl — there was no distribution, but at least they could sell some records at shows. Around the same time, they persuaded Dirtnap Records to put out their debut domestically, and it dropped to an eager audience in March 2003. “They kept sending me these CD-Rs of, like, just snippets of what would later become Guitar Romantic,” says Dirtnap’s Ken Cheppaikode. “I thought they were great. But it wasn’t until I heard the entire album, start to finish, that I knew it was something I really wanted.”

It was finally happening. Maximumrocknroll put them on the cover. Pitchfork gave their album an 8.8 rave — “The Exploding Hearts have released an album that is, at its core, ageless,” critic Matt LeMay wrote — and the album was doing well. (“The First Pressing (1300) of our debut album sold out in only 3 DAYS!!!,” Adam wrote on their website on March 23. “HOLY POOP!”) In April, they opened for U.K. punk legends the Adicts in Seattle, and in June, they opened a sold-out show for the Buzzcocks in Portland. “I just remember feeling like we were this unstoppable force — we were at this pinnacle that I wanted us to be in for so long, playing with these bands that I worshiped,” says Six. “I felt like, OK, this is the path. It felt like the doors were opening for us.”

JEREMY GAGE WASN’T ever 100 percent sold on the Exploding Hearts. By the time the band got together, he had landed a steady job at a call center for the local utility Pacific Power. “He was making good money,” remembers his roommate Joel Goodman. “His life was kind of on shifting sands for a while, after his parents got divorced. He wanted something that was stable.”

But music was innate to him. “He came out a musician,” says his sister Jenny. He taught himself every instrument he could get his hands on — even her harmonica — and at home he’d blast records in his bedroom, drowning out the TV in the family room next door. “He would be in there, head-banging,” says his brother, Jamie.

Jamie saw Jeremy’s music as one of his many hobbies — “just like his skateboarding, or his writing” — but he was still surprised when, after the Exploding Hearts began taking off, Jeremy seemed to back away. “As soon as he got to a place where his music was actually possibly going to take him somewhere, he was having doubts,” Jamie says.

In early 2003, Gage quit the band. “At the end of the day, he just didn’t want to commit,” Six says. “He wanted to play in what he described as ‘shitty punk bands,’ to go crack beers after work and play with his buds.”

There was only one problem — Cox, Six, and Fitzgerald couldn’t find anyone who could live up to him on drums. “Nobody could grasp the concept of what we were doing,” says Six. Potential drummers would try out, and either make it too complicated or fall apart at the end of the beat. “I think Jeremy knew how much trouble we were having, and in some fucking sadistic way he enjoyed it,” Six says, half joking. “Because he felt like, ‘Ah, you guys can’t replace me.’”

Every once in a while, when they had a gig too big to pass up, they’d talk Gage into joining them onstage one more time. One such gig was in May 2003, when the Harvard Lampoon flew the band out for its first East Coast show. Nick Sylvester, an undergrad Lampoon staffer who also wrote about music for Pitchfork, had been playing their promo CD nonstop in the satirical magazine’s headquarters, a mock-Flemish castle near campus. Sylvester had pitched the idea of an Exploding Hearts show to his Lampoon friends — led by future Saturday Night Live star Colin Jost — and they were down. But as the band and their manager were en route to Massachusetts, everything fell through for reasons that may or may not have included a threat from campus authorities.

The band was mad, so the kids from the Lampoon came up with a backup plan. They got all the equipment into the castle and took the band out to dinner at a fancy restaurant nearby, “this absurdly French bistro,” remembers Six, who claims he ordered the most expensive bottle of wine on the menu just to see what he could get away with. “I was like, ‘OK, sure, I’ll eat lamb cheeks and bone marrow, that sounds great.’” (Gage didn’t make it to dinner. Instead he discovered a secret tasting room in the castle and helped himself to some brandy and a nap.)

“As soon as [Jeremy] got to a place where his music was actually possibly going to take him somewhere, he was having doubts”

When they got back to the building, Sylvester says, they sneaked the Hearts back inside and ushered them to “basically an unfinished basement with fluorescent lights, exposed pipes — just absolute trash.”

The show was nuts. “It was wall-to-wall Ivy League college kids in, like, distressed and fucked-up tuxedos, because they’ve been partying all night,” Six remembers. “There were these pipes from the 1800s, and they were just grabbing on them. That was probably the wildest show we ever played. For a second, I’m like, ‘We could die down here?’ It felt like the walls would just fall down.”

On the way home from Massachusetts, Gage had a premonition of his own. “On the plane ride back, Jeremy popped open the window and was like, check this out. Lightning was striking the wing of the plane,” Six says. “He’s like, ‘We’re totally gonna die.’ He said it in a way that was just so matter-of-fact. I thought it was the funniest thing I’ve ever heard.”

That April, Fitzgerald had obtained a new van, a “Dodge piece of shit,” as Six remembers. “It was an early-Nineties model that was, you know, something that we could afford.” (“She is a green beauty!” Cox wrote on their website at the time.) “The van became his baby,” says Molly, Matt’s sister. He parked it in their stepdad’s garage, which had all the lifts and tools Matt needed to fix it up. “He worked on that thing all the time,” Molly says. But it needed a lot of work. “That van scared me,” Aronica says. “I didn’t want to take it. I tell you, I had to pick my battles.”

Early on the morning of Thursday, July 17, 2003, they all piled in, including Gage. “It was 6 a.m., and for me, that was an ungodly time to be awake,” says Six. He fell asleep in the back seat and woke up when they were outside Weed, California — almost there. They got into town, ate some Mission Mexican food, did an interview with Thrasher magazine, and played Bottom of the Hill.

Aronica remembers having a heart-to-heart with Gage the next day. He still wasn’t sold on the band, but he seemed to be coming around to their manager. “We were watching TV, hanging out, and he said, ‘I’m gonna go smoke a cigarette,’” she remembers. “About five minutes later, he came back in and said, ‘Hey, could you come out with me?’ So we hung out and talked some more. I needed that.”

That night, at Thee Parkside, Gage was feeling uncomfortable with all the attention he was getting. “People were coming up to him, because they wanted to get to know him, you know? There’s so much interest in the Hearts,” Aronica says. “And he goes, ‘Do I have to talk to these people?’ And I said, ‘Why don’t you just stand next to me?’ And he was like, ‘OK.’”

The next day, they were back on the road.

TERRY SIX HASN’T told this story much in the 20 years since it happened — maybe four or five times total, he tells me during one of our multi-hour Zoom calls this summer. He told it to the cops, to a radio station, to Fatehi, for the as-yet-unreleased documentary. But when the shift comes in our conversation, when I ask him what happened next, after Parkside, he starts at the beginning.

After the show, Matt drove everyone back to the house where they were staying and parked the van in a Safeway lot overnight. Terry, seeking a little time alone, opted to sleep in the van. In the morning, using his pre-smartphone sense of direction, he was able to find his way back to where the others had stayed. Late on the afternoon of July 19, they started back to Portland.

It was already dark when they stopped at a roadside saloon, “this backwoods, shit-kicker bar in central Oregon,” Six says. “We walked in, and there was like one of those record-needle screeches — all these cowboys looking at us in full makeup and all that shit. They were not having it. I thought we were gonna get murdered.” They ran out, damaging the bar’s wooden fence on the way. “The bartender comes out and screams at us, saying that they’re gonna call the cops,” Six says. “I think there were guns brandished as well.”

After escaping to the van and taking off, they decided to find a place to sleep for a few hours. “Matt took this exit and found a place where he could hide the van a little bit,” Six says. “And we camped out there for the night. I remember waking up in the morning to the sound of the engine starting. It was really early. I remember I couldn’t see anything but green brush everywhere.”

Matt guided the van back onto Interstate 5, which twists its way up Oregon from the California border toward Portland. They had been on the road for 20 or 30 minutes when Six started to feel the van drift into another lane, then overcorrect. “That’s what led to the flip,” Six says.

“None of us were wearing seatbelts, except [Ratch],” he continues, launching into this part of the story with vivid clarity. He remembers pushing his hands against the ceiling and wedging his right foot under one of the benches, stabilizing himself as best he could. He remembers feeling the ridges of the pavement on his palms, through the van’s ceiling, each time it came in contact with the ground.

“I remember cartwheeling with the van,” he says. “I don’t remember being scared. I could hear our gear getting thrown out; I could see it kind of fly around in the van. I just remember thinking, ‘We’re gonna have to walk home.’ I honestly didn’t think anything bad was gonna happen out of it, other than all our gear was gonna be shot to smithereens.”

When the van stopped flipping, he fell back onto the seat. “I remember looking around, and everybody was gone. Ratch popped up from the bench in front of me and looked at me. Her head was bloody and had glass all through it. And then I remember thinking, ‘This is bad.’”

He got out of the van and ran to Adam, who’d been thrown outside. “I stood over him, and got down,” Six says. “I remember him taking his last breath.”

When he looked around, he saw something out of a nightmare. He saw the equipment spread behind the van, and he saw Gage and Fitzgerald. Someone with a fire extinguisher ran from the other side of the freeway to put out the flames that were starting to rise from the van.

“I just remember sitting down in the middle of the freeway, and I completely felt helpless,” Six says. “I didn’t know what to do.”

The next few hours are relatively clear: He was taken to the hospital and told that Cox and Gage were gone. Kearns came to get Aronica, and the three of them said goodbye to Fitzgerald, who died in the hospital. But the time after that is a haze. Six moved back into his parents’ house in Beaverton, where friends would come visit him to play board games or take him into the Oregon woods to clear his mind. “I don’t think I spent a night alone for a good couple months,” Six says.

Everyone I talk to remembers where they were when they got the call. Some were in bed, like Cox’s mom, who had woken up earlier with a start and the feeling that something was terribly wrong. Jessica Sawyer remembers she was in her dorm room, cutting the sleeves and neck off an Exploding Hearts T-shirt; the news sent her crashing to the floor. Across the Portland underground, word spread through a network of landlines, impromptu gatherings cropping up at houses and diners for people to cry, or just stare blankly into their food.

“I really want people to remember them, and I want them to know how hard they worked and how special they really were,” Aronica told the Seattle Times in an interview published barely 48 hours after the crash. “The other thing in my mind, of course, is how am I going to survive without them.”

AT SOME POINT, Six realized he was going to have to get a job. In the months after the accident, he’d sat through funerals, memorials, and benefit shows, populated by seas of people he knew and many he didn’t, crowding up sidewalks like a Portland punk-rock version of Rudolph Valentino’s funeral. He hated the internet, and had barely received emails before. Now, his inbox was a steady stream of condolences he did his best to avoid.

Six knew that he needed to begin reengaging with the world. “I had to switch gears quick,” he says. Before, the band had been his job; around May 2004, he started working at Dante’s, a local club where the Hearts used to play, and moved back to the city.

But being in Portland was excruciating. He could feel everyone he talked to taking pains not to ask about the Exploding Hearts, or worse, actually bringing them up. He could remember a time, not even that long ago, when people made fun of their band, called them names, didn’t show up for their gigs. Now they talked about the profound potential that was so senselessly lost. “It was miserable,” Six says. “I was coping, abusing whatever toxic substance I could get my hands on. I remember feeling like I was completely alone with what happened to me.”

Around this time, he joined a band called the Nice Boys, which had a more cleaned-up power-pop sound. They put out a few singles and one fantastic album, and toured pretty extensively. But he says now that he spent the entire time feeling checked out. “A lot of people told me, ‘That’s so great. I’m glad you’re doing this,’” Six says. “In hindsight I wasn’t ready. I remember being angry and upset and unhappy and depressed through that whole time. It was a distraction from ultimately what I needed to deal with.”

In 2006, Dirtnap released Shattered, a collection of Exploding Hearts B sides and unreleased takes. “I wasn’t even talked to about that,” Six says. “It just came out.” He was shocked — furious that no one had even mentioned it to him until it was already pressed — but he admits now that he might have left others with the impression that he wasn’t open to talking about the band: “Maybe that was the attitude I gave.” (Cheppaikode, for his part, says he was told Six “didn’t want anything to do with Exploding Hearts” at the time.)

Six was in a terrible place, but on his 27th birthday, he had a revelation. “As cliché as it sounds, I didn’t want to join the 27 club,” he says. He’d made a choice in that van. “I remember feeling so clear in that moment when we were flipping around, that I was reaching to hold onto whatever I could. I was like, ‘Look, man, you made a choice to be here. So what’s it going to be?’”

AS THE TENTH ANNIVERSARY of Guitar Romantic approached, King Louie Bankston had an idea: What if he and Six hooked up to record some new music? The two had spent an extended time not talking, Bankston having had a particularly bad reaction to the news of his friends’ deaths — delivered by Six in one of the first calls he made after it happened. “He was devastated,” Six says. “He processed it in his own way. We both kind of just felt that we needed to separate from each other.”

By 2013, though, they were back in touch. A few years earlier they’d linked up to play as Terry & Louie, a quick acoustic set at a two-day festival Bankston put on to showcase his many bands. A promoter had suggested they play a few Exploding Hearts songs. Terry didn’t really want to, but Louie talked him into it. “We’ve got to do this at some point,” Bankston told his former bandmate. “Let’s just have fun with it.”

Now, the two old friends rented a bomb shelter in Oakland, California, where Six was living by then, and recruited a friend to play drums on a few tracks. They played a couple of shows, and then a few more, a mix of new songs and Exploding Hearts hits. Before they knew it, they’d brought in new members, and Terry & Louie had become an actual band. “It was an excuse to get out of my daily grind and go play,” Six says.

Playing Hearts songs again was thrilling at first, but after a few years, Six began to sour on the project. “It just felt like, at times, we were like a tribute band,” he says. In 2019, after a tour in Japan, he called off his next planned tour with Louie and sent everyone home. “We had one conversation where we said things that we didn’t mean, and it was hard,” Six says.

He and Bankston talked once after that — a check-in call during the pandemic. “I think we were just going down two different paths,” Six says.

Six went about recording a new album of his own with Guitar Romantic producer Pat Kearns, who’d built an off-the-grid recording studio in the desert, not far from where both men now live. He worked on that album for a year and a half. Early on the morning of Feb. 14, 2022, he got a call. “I woke up at 4 a.m. to Colin Jarrell letting me know that Louie had passed away,” Six says. “I was gutted. I didn’t feel like we got to have our full closure. I thought we were gonna have more time. And we didn’t.”

It dawned on Six that he was the only Exploding Heart left. That’s when he dropped the idea of a solo project and turned to memorializing the 20th anniversary of the album that had brought them all together. “I realized that it was just completely, solely on me now,” he says.

JULY 21, 2023: It’s after 1 a.m. in the green room at TV Eye. “I feel fulfilled,” Six says. He’s seated on a stool, camera trained on his face. He’s talking to Ardavon Fatehi, as he has many times over the past eight years, since Fatehi began documenting his life. His wide eyes are open extra wide. The 20th anniversary of the tragedy that tore his life apart has passed, and he’s survived, again. “I finally feel like I can say goodbye — something I’ve never wanted to do,” he says. “I feel like after tonight I’m that much closer to the point where it doesn’t belong to me anymore.”

Six has been backstage since the early evening, entertaining close friends, band acquaintances, and Gage’s brother and sister, who have flown in for the occasion. Drummer John Tyree and bass player Chad Savage, both of whom played in Terry & Louie, are there warming up, as is Murat Aktürk, a longtime friend and accomplished guitarist whom Six called in for these gigs. Paul Collins, the guitarist and singer of the Nerves, is hanging backstage too. He’s known Six a little since the Terry & Louie days — when they, like the Hearts, would cover his song “Walking Out on Love” — and he’s here for a surprise performance of it during the encore. (He’s a big fan of the Hearts’ music, too. “They have a lot of substance and grit,” he later tells me. “This stuff is the real deal.”)

Nick Lowe’s “So It Goes” starts playing over the PA. The members of tonight’s band get in a circle, foreheads together. They’re mostly wearing gray, black, and red, but Tyree has on a light pink suit, and Six is rocking white jeans, a little nod to his old look. Onstage, a short film that Fatehi has cut together starts to play. It runs through the band’s history — news clips from their rise and their demise flash on the screen. The screen goes dark. The four men run onto the stage.

The opening chords of “Modern Kicks,” the first song off Guitar Romantic, send everyone over the edge. There are screams and tears. “Hearts are breaking now, she says I don’t care!” Some people have heard the album once or twice, others thousands of times. But from the first line, everyone is singing along.

Onstage, Six is having a somewhat surreal experience. He’s the frontman now, standing in for Cox. “I’ll look back at Chad and sometimes I’ll see Matt,” he says later. “Same with John. Then I’ll look over at Murat, and he’s doing the same shit I was doing. I feel pulled from my own body.”

After the set, staring into the camera, Six says he was skeptical of doing these anniversary shows, worried what people might say. “I’m not doing this for money. I’m not doing this to sell records, or get likes on a fucking page,” he says. “I don’t want anything that I do to be [seen] as me exploiting the memories of the dead for my own personal gain. That is a lot of the reason why I have shied away from interviews and basically doing any of these shows, and keeping myself in the dark for many years, and keeping myself numbed and away from everything.”

A month and a half after he leaves TV Eye, the five-show run is scheduled to end with a homecoming gig in Portland on Sept. 9. Maybe then, the record that Six has held onto so tightly, that’s shaped his entire life — “something that I guarded, something that I’ve been jealously and selfishly trying to preserve” — can be in his past, too.

“I’ve been trying to keep this memory and these guys and their work alive for the last 20 years,” Six says. “And I feel like there’s not much I can do after this point…. After Portland, I honestly feel like I can go about my life again. It’s in good hands.”

Best of Rolling Stone