Back in the New York Groove: ‘Armageddon Time’ Director James Gray Talks His Long Trip Home

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

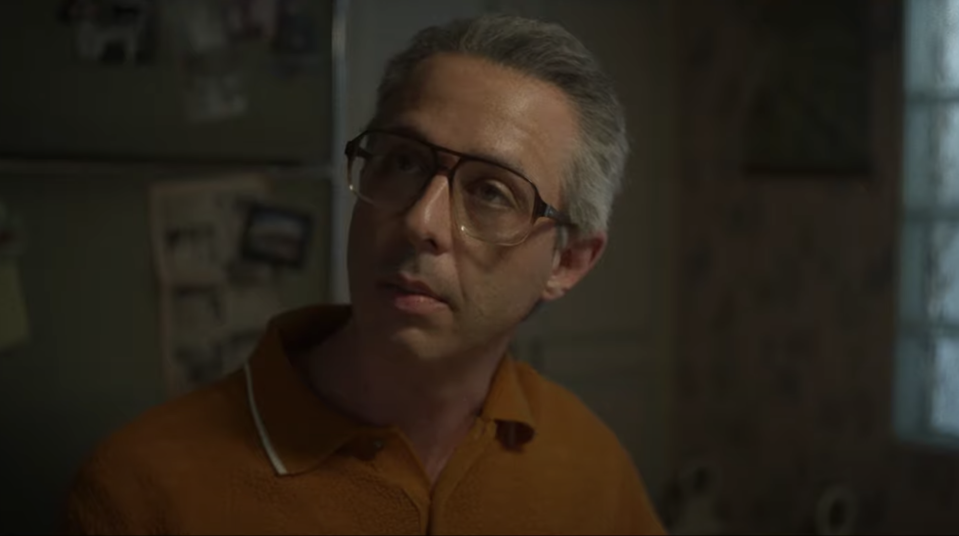

“I’m tired,” James Gray said over Zoom from Los Angeles, where he’d just returned from shooting a commercial in San Francisco. “We finished last night and I flew back late. As an aging Jew, I’m now in the habit of sleeping terribly. I don’t know what that is or what the solution might be. I wake up at 3:00 a.m. every day. It sucks, but anyway.”

While anyone familiar with the self-conflicted richness of Gray’s work (and/or the colorful borscht of his personality) should know better than to assign his anxieties to a single source, it seemed possible that he just might have been feeling nervous. A few days later, the 53-year-old Flushing native would be traveling back East for what seemed like the most emotionally fraught screening of his entire life: The New York Film Festival premiere of his autobiographical coming-of-age drama, “Armageddon Time.”

More from IndieWire

James Gray and 'Armageddon Time' Made Anne Hathaway a 'Better Actor'

'Personality Crisis: One Night Only' Review: Scorsese Pays Tribute to the Ultimate New York Doll

It would be a homecoming, but also a reckoning. In a sense, it would be a moment that Gray had been running both from and towards at full speed since his career began some 30 years earlier — a career that started by trading Utopia Parkway for USC, and has since taken the invariably personal filmmaker from Neptune Avenue (“Little Odessa,” “Two Lovers”) to Neptune itself (“Ad Astra”) in search of the distance required to make a movie about the New York that made him.

That distance has been the major subject of Gray’s seven previous features, all of which push against the gravitational pull of home with the strength of someone who knows he’ll never fully escape it. His movies are the product of an avowed classicist who once put an Applebee’s on the Moon because life had taught him that we bring the past with us wherever we go; they’re the product of a comfortably uncool Coppola fetishist who believes in America to a certain extent, but tends to be suspicious of assimilation.

From the doomed crime saga of “The Yards” to the operatic Ellis Island melodrama of “The Immigrant,” the majority of Gray’s work takes place in the context of a city that has always been defined by the tension between what people take with them and what they leave behind. His films sublimate that tension into nuanced, timeless, and intractably humane stories about fathers and sons. They position family as both the ultimate source of comfort and the greatest potential source of pain (a dialectic made so vivid by the end of NYPD thriller “We Own the Night” that even Mark Wahlberg manages to endow his final “I love you” with the weight of a Greek tragedy).

They are at once both sweepingly mythic and unambiguously personal. They are often sweepingly mythic because they are unambiguously personal.

Before “Armageddon Time,” Gray’s wariness towards assimilation had extended to his relationship with his own work. He was embarrassed of his background — not just because of his father’s role in the commuter rail scandal that was revisited by “The Yards” — and afraid of making himself vulnerable. At the start of his career, Gray told loosely autobiographical stories that used genre as a protective barrier between himself and his art. As time went on, his films only became more personal as they drifted away from his lived experience.

2008’s “Two Lovers,” which stars Joaquin Phoenix as a bipolar man whose heart breaks for the shiksa goddess who feeds his fantasies of leaving Brighton Beach, is about someone who’s embarrassed of his background and afraid of making himself vulnerable (in reality, Gray married his shiksa and moved to Los Angeles with her just in time to make a lavish period epic about his family’s arrival in New York).

2016’s “The Lost City of Z” is an “Aguirre”-like adventure about an early 20th century explorer who would rather die an uncertain death in the Amazon than live another day in the English society from whence he came.

2019’s “Ad Astra” elevated Gray’s usual obsessions to cosmic new heights — the film’s Campbellian astronaut is so determined to flee his feelings that he volunteers for the same world-saving mission that may have killed his father, only to reach the edge of the galaxy and discover that self-understanding is the only way to change one’s fate.

It’s a message that might have rang false had Gray not followed through on it in his own life. It took almost 30 years, but he’d finally backed himself into a corner where he had no choice but to go back to Queens and make the unvarnished autobiography that he’d spent his entire adult life trying to avoid.

“You’re not projecting,” Gray reassured me when I presented him with that narrative. “I mean, those are the facts of the case. I remember telling [The New Yorker writer] Nathan Heller that it was time for me to revisit the city and to make the most autobiographical thing that I could as a rejection of the idea that looking outward would give us the answer. And it doesn’t really. We can’t understand the infinite with regards to the universe — it doesn’t mean anything. It’s an abstraction. All we can try to uncover are the many layers inside our own souls, which are also endless. That’s why ‘Citizen Kane’ is so enduringly brilliant.”

Which isn’t to suggest that Gray has any regrets over his recent spate of epics. “I’m not bad-mouthing those films,” he said. “I’m very proud of them, especially ‘The Lost City of Z,’ which was something that I had long dreamed of doing in order to honor my gods. But I won’t lie to you: It was physically punishing. It’s one thing to state, ‘I’m going to Amazonia to make a movie and just be a cool dude hanging out in mosquito-repellent clothes,’ but it’s another to actually do it.”

Gray segued from the verdant jungles of Colombia to the green screens of California, which may have been even further out of his comfort zone. “At a certain point you didn’t want to have to build a set and string Brad Pitt up on wires, you just wanted to walk in somewhere and directly relate to the space in front of you,” he said. “I just wanted to try and rediscover my love for the movies beyond the logistics of making them.”

Getty Images

It would be an understatement to say that Gray could directly relate to the spaces that were put in front of him on the set of “Armageddon Time,” a burnished coming-of-age memoir that cleaves so close to his own memories of sixth grade that its characters eat off the same plates that his mom once used for family dinners.

In truth, “Armageddon Time” challenges the clean beats of narrative convention by blurring any kind of clear personal growth across the fault lines of racial inequality, the devil’s bargain of class mobility, and the moral compromises demanded by the American Dream. If Gray’s previous movies laundered personal details through established tropes, this one flips that script by laundering established tropes through personal details.

In making “Armageddon Time,” Gray found that some of those details were on the verge of disappearing. “The unsettled truth is that the space of New York City and the city itself has changed so profoundly since I was a kid that my ability to personalize my own experience was somewhat limited,” Gray said. “When I was growing up in that neighborhood, it was very much an Archie Bunker kind of place. It was a white working-class WASP population, with those nauseating slave statues on a couple of the lawns. Today you go back there and it’s almost exclusively Asian and Orthodox Jewish people, and so in some ways there was a kind of archaeological quality to what I was doing.”

Situated just a few blocks from the exterior locations Gray shot for the movie, his childhood house looks more less the same as it did 42 years ago, but the gate that his father built to box in the garbage cans is the only physical evidence that remains of his family.

“Just to be very pretentious on you,” Gray continued, teeing up a “Swann’s Way” reference with one of his signature pleas for forgiveness, “Proust talks about how the places you live in and the lives you lead and the people you know are all impermanent. They all change and disappear. They’re all tangible and temporary.” For Gray, that phenomenon is even more pronounced in New York. “The city has that beautiful European touch to it because it was settled by the Dutch and not the English,” he said. “It has that melancholy sense of history — it’s layered with our ancestors’ lives. You can still smell it. You can almost touch it.”

That “almost” goes a long way for Gray, who felt neither accepted nor rejected by New York upon coming back to film here, but was struck by a profound sense of loss. “That sense of loss probably infuses the work,” he said, reflecting on the decision he made to go out West for college, and how suddenly home evaporated once he left (within three months of leaving for film school, Gray’s older brother moved out under fraught circumstances and his mom died from the brain cancer that was transposed onto Vanessa Redgrave’s character in “Little Odessa”).

“I guess I needed to get out of the city for a little bit,” he said. “There was an aspect to it which felt a little oppressive to me. I’m not someone like Martin Scorsese who grew up in Flushing and then moved to Elizabeth Street and then went to NYU. I didn’t move. I stayed in one place in this room in my house for my entire childhood and there was something that felt suffocating about it.” Gray let that sit for a moment. “Plus, honestly, USC just offered me scholarship money, which I had to take.”

If leaving home is what launched Gray’s career, the films that he’s made have finally lead him back to it. Set across a two-month stretch in the fall of 1980 and told through the eyes of an oblivious 12-year-old named Paul (Banks Repeta) who’s too locked into his own pre-Reagan present to understand why his beloved immigrant grandfather (Anthony Hopkins) encourages him to “remember your past,” “Armageddon Time” revisits Gray’s brief and scarring friendship with a parentless Black schoolmate named Johnny (Jaylin Webb) who wasn’t afforded any of the same protections or second chances that he took for granted. It’s perhaps the most lucid and damning film ever made about the specifically Jewish experience of assimilating into the same conditional whiteness that a previous generation had to escape.

It’s also perhaps the most logical origin story for a filmmaker whose work has always been wracked by a bone-deep belief in the plurality of being, and has often seemed to use story as a catalyst to help him reconcile the conflicting feelings that he’s had about the people and places in his own life.

That’s why Gray’s movies reject almost any clear moral judgment; it’s why the warm and wistful film he’s made about the most shameful moment of his childhood isn’t the least bit self-aggrandizing or sanctimonious, and why it lovingly recreates his formative years even though his father (played in the film by Jeremy Strong) beat him, and his favorite grandfather forced him to trade P.S. 173 for the Trump-supported Kew Forest School. “I’m not a big fan of pointing fingers and blaming others and proving my superiority,” Gray said. “I’m a deeply flawed person, and guess what? So is everybody else. That’s the point of art.”

Getty Images

That much is evident to various degrees throughout “Armageddon Time,” in which Gray’s pre-pubescent avatar is — in the director’s own words — an “obnoxious jerk.” As proof, Gray imitates the way that Repeta shouts “dumplings, suckers!” at his mother (Anne Hathaway) when he orders Chinese food instead of eating the dinner she made him. In fact, young Paul is so painfully incapable of saving Johnny from a situation he created that some have dismissed this movie as the work of a white artist who’s trying to absolve himself of failing his Black friend.

Gray objected to that take on one very specific point: “I want to be clear about something,” he said. “I do not feel guilt [about what happened to his friend]. When you’re 11 or 12, you do not have the moral or ethical foundation to grapple with a world that is unendingly complex. You are both biologically and educationally ill-equipped for such a task. I think my behavior at times was utterly disgraceful and gutless, but at the same time I don’t know what the heck else I could have done at that age. And so I don’t look at it with guilt. I look at it and say ‘this is warts-and-all and it’s embarrassing, but that’s what the world is and was.’”

That helplessness is reflected by a film that refuses to use Johnny’s plight as a spectacle for Paul’s decency, focusing instead on the struggle to be a mensch in a prejudiced system that makes complicity a prerequisite for advancement.

“Armageddon Time” holds Gray’s striving parents accountable for their compromises, but it also loves them for their tenderness. “Of course I wanted to memorialize them,” Gray says of these characters (his father died of COVID earlier this year). “I wanted to say that despite all their flaws — and they had many — there was beauty in them to me.”

His career makes good on the film’s suggestion that Paul learns a different metric for success. Gray insists that he’s never made a movie for money, and even his harshest critics would have to concede that point. “I will admit to something which is probably hopefully pompous and unintentionally arrogant sounding,” he said. “I’ve never thought the reviews or the box office was the ultimate measure of making films. I always thought that it’s a marathon and not a sprint. That being a creative person is to try — and sometimes I fail at this — but to try and block out the noise and just express yourself personally over and over and over again. ‘To fail and fail better,’ as Beckett said.”

Focus Features

Gray ascribes “making it out” to good luck, even though “Armageddon Time” offers a nuanced understanding of how luck tends to work in this country. He often likens making it in this country to winning the lottery (which adds a fun twist to one of the many commercials he’s directed between features), and sees New York City as the most cinematic expression of the randomness and cruelty that shape the American Dream. “There’s a viciousness and unsentimentality about the city,” he said, “an unbridled capitalism at its height. Look at the architecture. All the buildings are so tall. How do we maximize real estate? We have the corporations look down on you. It gives New York an excellent dramatic impulse, which immediately makes a very different and violent statement. If I made ‘The 400 Blows’ in this city it could never be…,” at which point Gray started humming Jean Constantin’s effervescent score.

All this talk of skyscrapers makes it easy to forget that Gray has seldom worked in Manhattan, as most of his movies are confined to the outer boroughs. For a long time, it seemed like Manhattan was equally uninterested in him. NYFF, which is based in Lincoln Center, didn’t program one of his films until “The Immigrant,” long after Cannes had elevated him to the world stage. “Even that was a fight,” Gray said. “Not with the festival, but with Harvey Weinstein, who didn’t want the film to play there.”

Did it sting that Gray’s hometown fest was slow to appreciate him? “I guess it did,” he said. “It feels a little remote to me now, but I remember really wanting to get ‘The Immigrant’ to play in New York, and when Harvey said he wouldn’t let it, I remember being totally heartbroken. So yes, there’s something about showing films there that makes it a little extra special. It’s very moving to me.”

“It’s also very scary,” Gray added, and it’s never been scarier for him than it will be with “Armageddon Time.” “It’s like showing the movie to my brother or something,” he said, “which, by the way, I’m going to be doing at NYFF.” His brother’s presence has been felt across his body of work, but this is the first time someone’s actually playing him on screen. “He hasn’t seen it yet,” Gray said, “and I’m very close to him. He’s a beautiful person. I have no idea what he’s going to think.”

Most of the people who are portrayed in “Armageddon Time” are no longer alive to see it, which adds to the feeling that Gray made the movie to exorcize many of the ghosts that have haunted his entire body of work. Asked if this most autobiographical film has finally satisfied his need to tell New York stories, Gray insisted that he wasn’t sure what its effect on him would be. “The honest answer is that I just don’t know. I’m still weirdly in the movie,” he said, well aware that a part of him always will be. “I haven’t shaken it, and I don’t know what I want to do next. I’m at a little bit of a loss. But I don’t think it’s about exorcizing anything for me. I think the job of the artist — if I can use that word — is to find what’s wrong with the world through what’s most vulnerable about us, and then reveal that to you.”

Did Gray enjoy the extra layer of vulnerability that was inherent to making “Armageddon Time?” It’s complicated. “I mean, ‘enjoy’ is a word,” he said. “Yeah, I enjoyed it. Here’s how I would answer that: It felt like there was an extra level of fulfillment to it. Does that mean ‘Oh, I’ve done it, I’m the greatest’? No, the opposite. But at the same time, failure is inevitable. It’s just about if you can express yourself with clarity. Can you try to at least grow, and expand your horizons, and do something beautiful and true to yourself in a different shape. And this felt like I had at least begun to try to do that.”

When “Armageddon Time” premieres at Alice Tully Hall, it will mark yet another well-deserved homecoming for a bonafide New Yorker who’s never been able to stay away for long. But more than that, it will also be a chance for audiences to watch a local artist — if I can use that word — truly see himself in his city for the first time.

Focus Features will release “Armageddon Time” in select theaters on Friday, October 28.

Best of IndieWire

New Movies: Release Calendar for October 14, Plus Where to Watch the Latest Films

Martin Scorsese's Favorite Movies: 50 Films the Director Wants You to See

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.