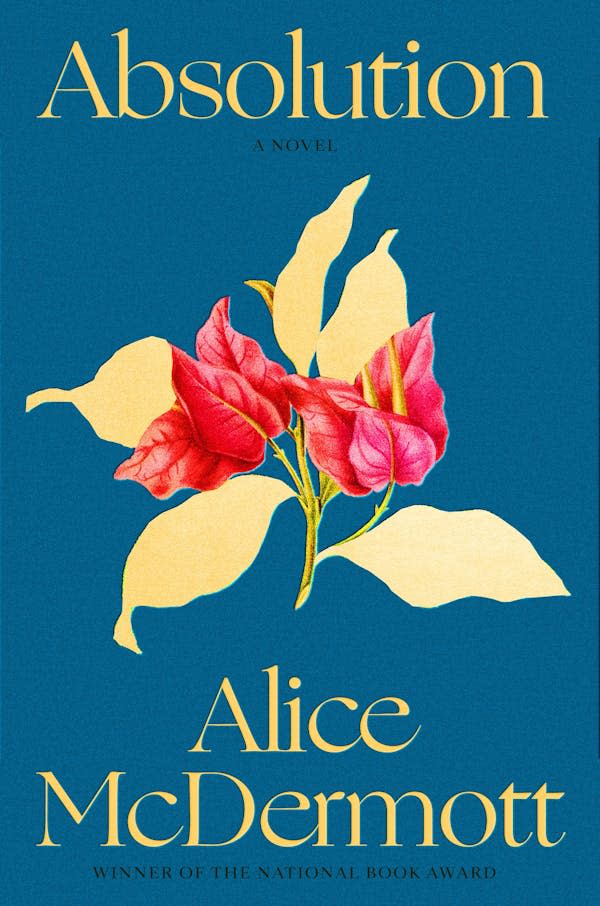

Award-winning novelist Alice McDermott to appear at the Savannah Book Festival

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It feels easier to look away when life presents us with the uncomfortable. But National Book Award-winner Alice McDermott’s latest novel, “Absolution,” is a tale of murky motives and hidden perspectives that invites audiences to resist the urge to turn away.

“I hope readers will re-examine their own certainties, maybe find absolution for themselves or others, past and present. T.S. Eliot has a line: ‘We had the experience but missed the meaning.’ First and foremost, I hope readers come to the end of the book feeling they have had the experience,” McDermott said. “Then I hope they'll think about the meaning.”

Our experience of “Absolution” begins in 1963 Saigon, where Irish American New Yorker Tricia Kelly settles into her role as a “helpmeet” to her Navy engineer husband. While at a cocktail party, Tricia meets Charlene, a “dynamo” and fellow “helpmeet” whose youngest child gets sick on Tricia’s dress moments after Charlene swoops into the scene. While Lily, a talented seamstress and house girl, cleans the dress, Tricia meets Charlene’s daughter, Rainey. Soon it becomes clear that Tricia isn’t the only one benefiting from Lily’s skills as she presents Rainey with a Barbie doll-sized ao dai, Vietnam’s national dress consisting of a split tunic worn over silk pants.

The moment sparks Charlene’s next charitable venture and provides a glimpse into the experiences that breathed meaning into this story.

McDermott finds the stories omitted from the history books

“Absolution” was inspired by several experiences, starting with Graham Greene’s “The Quiet American,” a novel that McDermott said was “politically prescient about US involvement in Vietnam, but absolutely clueless in its portrait of women.” After moving to the D.C. Beltway over 30 years ago, she met some of the women whose stories were omitted from the history books.

As she listened to one military wife speak about the Barbie doll clothes she’d made from leftover scraps, McDermott was reminded of the ao dais she’d seen on a childhood friend’s doll.

“That coincidence over so much time and space intrigued me,” McDermott said. “I was also intrigued by a story I had heard years ago about a father who sacrificed himself to save the life of his Down syndrome son—a gesture that in many ways began the book for me and remains at its heart.”

To thread these memories into an authentic narrative, McDermott immersed herself in research, looking at historical events from a 1960s perspective rather than modern eyes.

In conversations with former “helpmeets,” McDermott quickly discovered many women were reluctant to discuss their experiences unless prompted, explaining why there are so few accounts from women. This observation led to the question of what would prompt Tricia to tell her story, resolved in the novel’s framing as a correspondence between Tricia and Rainey.

“I knew Tricia would have to be invited to give her account, in this case by Charlene's daughter: ‘Do you remember me? Do you remember my mother? Do you remember Dom?’” McDermott said. “The questions that are asked before the novel begins.”

In these letters, Tricia reveals that she does remember Charlene. Tricia tells Rainey about her first miscarriage, and about how Charlene stayed by her side afterward. She also reflects on Charlene’s similarities to her childhood friend, Stella. As Tricia reveals more about their white savior missions, taking Tricia to a leper colony and halfway to joining the Freedom Riders in Birmingham, both women become imperfect challengers. They shift Tricia’s understanding of absolution.

“We expect, unfairly, that those concerned with doing good in the world must be thoroughly good themselves. As if any one of us is so uncomplicated! It's confusing the message with the messenger, I suppose. Charlene and Stella are both less than perfect, and yet both urge Tricia, and others, to resist complacency and helplessness in the face of suffering,” McDermott said. “They urge Tricia to think, challenge, question, do something—which, of course, is also a demand to take the risk of doing the wrong thing, of inadvertently causing more harm than good. (See the US in Vietnam.)”McDermott said Stella and Tricia’s friendship is a portrait of the often unacknowledged dimensions of women’s friendship, affording opportunities to discuss and debate without the fear of men stepping in to correct and condescend. McDermott said this dynamic “was true then, in the early sixties. But I fear it's no less true now. Mansplaining hasn't gone away.”

Although Tricia and Charlene gloss over their experiences with simple dismissals, McDermott points the reader’s eyes toward reality, subtle stories told in Charlene’s anxiously circling thumb and forefinger as well as the bodhisattva on Tricia’s dresser. Those careful moments create an experience whose meaning extends far beyond simple answers.

“I think of novels—the novels I read as well as the novels I write—as a gracious invitation to join another human mind to consider something—situation, character, story—together, just two minds (reader and writer) for whatever time it takes for the novel to be told. [It’s] an avoidance of the obvious—what we already know, what we can know without reading the novel,” McDermott said. “An appreciation for the subtle—what we discover through careful attention—seems an inevitable result of such a goal.”

For careful readers, that experience becomes communal at the Savannah Book Festival, and McDermott looks forward to visiting the city and all the stories tucked into the its rich culture.

“I have no Southern ancestry, but the parallels between the story-telling South and the story-telling Irish have always been clear to me. Always a kind of haunting, always some awareness of things unseen, in both populations,” she said.

Whether those hidden hauntings are found in the streets of Saigon or the squares of Savannah, the stories hidden within them may reveal our very nature. You just have to be willing to look.

If You Go >>

McDermott will speak about “Absolution” during Festival Saturday at 1 p.m., on Feb. 17, at First Baptist Church Sanctuary, 223 Bull St. For a complete schedule, visit savannahbookfestival.org.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Novelist Alice McDermott to appear at the Savannah Book Festival