The Authentic Genius of Michael Caine

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This article originally appeared in the December 1966 issue of Esquire. It contains outdated and potentially offensive descriptions of homosexuality, gender, and class. To read every Esquire story ever published, upgrade to All Access.

One of the more agreeable aspects of the recent British renaissance has been the emergence of the Englishman as a symbol of masculine sexual virility. For this, they can thank the rise of a youthful proletariat who, as everyone knows, are now setting styles—in fashion, speech, pop music, dancing, films, plays, painting, general behavior. It’s dead chic today to be working-class English.

The old concept of the Englishman—tea, butlers, stiff upper lip, and dressing for dinner in the jungle—was also frequently tinged with effeminacy, but the present impact of young, what-the-bloody-hell, non-U trend setters is changing the picture. You do not as a rule find a high incidence of swish among truck drivers, longshoremen and similar laborers. Their sexual mores are on a boy-meets-girl basis, and it is this happy leaven that is altering the old epicene image. From this proletarian background have come actors like Sean Connery, Tom Courtenay, Albert Finney, Peter O’Toole, Terence Stamp and now Michael Caine, as well as most of the pop-music groups and those writers following in the wake of John Osborne, who is himself of working-class origin (his mother was a barmaid) and who first signaled to the rest of the world the coming revolutionary changes in the national physiognomy when he wrote Look Back in Anger ten years ago.

No one exemplifies this transformation better than Caine. In his first starring film, The Ipcress File, last year—and this year in Alfie—he established his reputation not only as an actor but as an emblem of the new Britain. He is the coolest of them all and currently the most fashionable example of the crumbling of old class prejudice.

For Caine is a Cockney, and to have a Cockney—of a group formerly always good for a laugh but rating socially along with the Untouchables—emerge as a stylish trend setter, an arbiter of tastes, a model Englishman, a sex symbol instead of the comic relief, is really discombobulating the old caste setup. As the newest idol of the anti-Establishment cult, Caine finds, rather to his contempt, that where he eats, where he gets his clothes and what he wears, where he takes his girls to dance, have become newsworthy items. (“It must bore the pants off anybody with any intelligence,” he has said. “This New Aristocracy bit about actors, models and photographers is an idea I just can’t stand…. It’s so ‘in’ now to have a working-class background that any actor, painter or writer who is working class is automatically assumed to be great.”) Even his accent is imitated, and London debs interlard their conversation with Cockney phrases to show how sophisticated they are. Of Caine they say, “Isn’t it super? He’s a Cockney, you know,” which is about on a par with saying, “Isn’t it marvelous? He was born in the Bronx,” or “He has this divine Brooklyn accent.” (Only it isn’t the same, because in America practically all our celebrities were born in the Bronx or an equivalent social background.) Caine, himself, is getting pretty fed up with all the emphasis on the Cockney bit (“I wasn’t just standing outside some East End youth club with a razor in my hand and Harry Saltzman came riding up in a Cadillac and discovered me”), but he is going to be a lot more fed up before the brouhaha dies down.

“They always want to interview my mother because she was a charlady for twenty years, and they say, ‘Oh, those Cockney people, they’re lovely!’ and they start talking about eight notches below my intelligence and four below theirs. England is a socially prejudiced country, and I’ve been through all that. If you’re a Cockney, you’re made to feel you don’t belong. Certain hotels and restaurants, they hear your accent and they give you that thin-lip, glass-eye look. The Cockneys themselves say to you, ‘You’re just a bum,’ and you’re told you can’t ever do anything. When I was very young and said I was going to be an actor, my friends said I’d never make it. Not a little jump-top Cockney shit like me. They said I had a horrible accent you could cut with a knife and I wasn’t very good-looking. Well, that was their attitude and they’re stuck with it because now they’re thirty-three, too, and I don’t hear of them.... No, I never see any of my old friends. I haven’t got anything to say to them. What am I going to say—‘Yah! I made it!’? Then foreign journalists keep asking me about the pearly kings and queens. I get embarrassed by the pearlies. They’re from the old days when Cockneys were kissing the ass of the upper classes. They’d dress up in these ridiculous costumes and put on an act for the amusement of the nobs…. But I think this whole class bit is changing. Anyone can do anything now. The old public-school image is on the way out. Oxford and Cambridge. They’re building nine new universities—Sussex is one—and lots of guys will get in. Before the war, the student body consisted of lords’ sons who were all idiots. Now a whole new lifeblood is being pumped in—ballsy guys with some brains, from the working class. We don’t want to know any of this old crap.”

It was a Sunday afternoon in Berlin, and we were sitting in a restaurant called the Drei Bären, on the Kurfürstendamm. Drei Bären means Three Bears (not Beers, as I first thought) and Caine said that the film company, there to make Funeral in Berlin, had trouble because every time anyone ordered a dry Martini he got three of them. I catch on fast, so when the first straight vodka I ordered looked as if it had been measured in an elf’s thimble, I took to ordering drei vodka, although we had difficulty persuading the waiter to put all in one glass. Caine knows some German—he’s good at languages—and David Pelham, the press agent, speaks it because he went to school there, but I don’t speak any and don’t want to. Berlin is a hard town in which to feel popular. No one in the film company liked it, and everyone had a pet peeve to relate. The wardrobe woman was in a cab and lit a cigarette and the driver, without saying a word, reached back and took the cigarette from her hand and threw it out the window. Then he said, “No woman is going to smoke in my cab.” Pelham’s wife, who is Iranian and a cousin of Soraya, was pregnant and not feeling well, so she took a taxi for something like six blocks, and the driver bawled her out for not walking such a short distance and said, “That’s just like you decadent French.” Caine said he had his girl, a French model, visiting him, and they got in a cab on a cold day. “She was freezing, so I asked the driver to put his window up. He simply refused. Then when we got to where we were going, he began to swear at me. I would have hit him except he was so big he was spread out over his own seat and half of the other…. It’s different from anyplace I’ve been. I have not yet found in Berlin a social, uncommercial restaurant or bar or nightclub—well, I realize that no club is run as a philanthropic deal, but here there’s no such thing as anybody being pleased to see you in any of them. They’ll hang two bucks on you for a small Scotch, but they won’t even say hello when you come in or good-bye and thank you when you leave.... I don’t want to be unfair to anybody, so let’s just say we’re dancing to different tunes. It’s not my scene.”

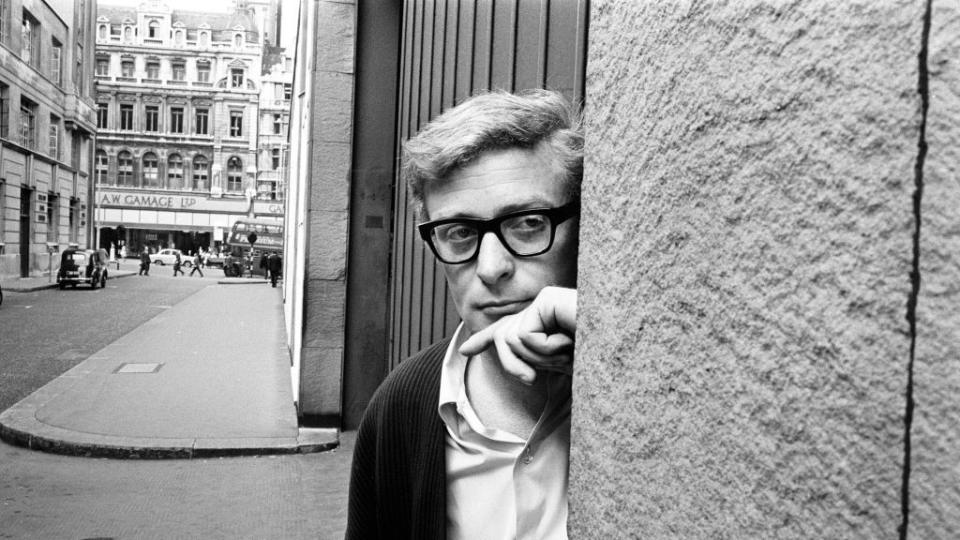

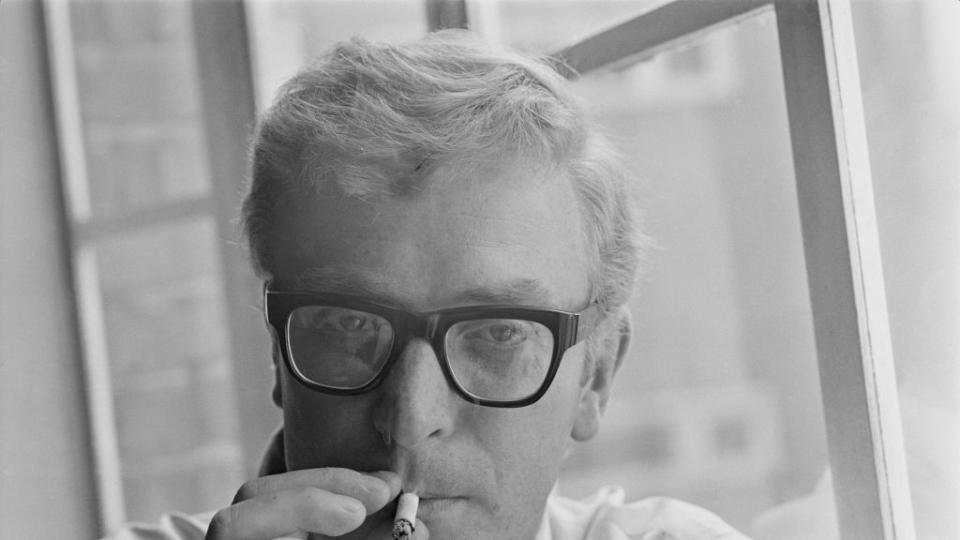

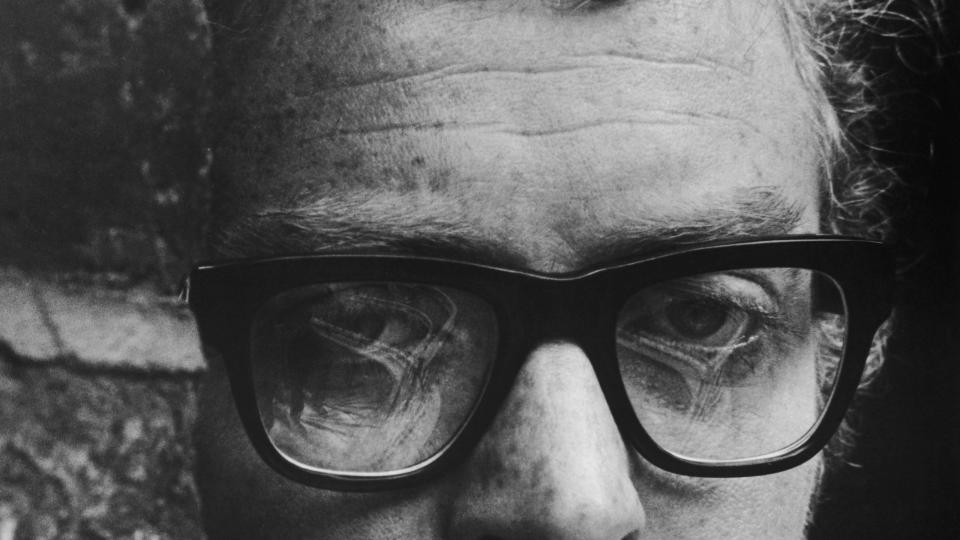

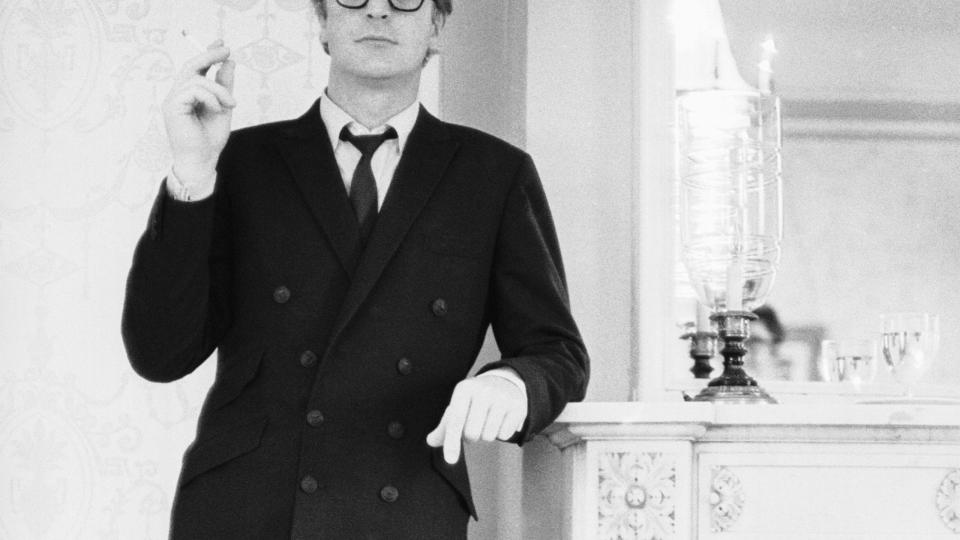

I had flown in that morning from London. They were filming nights, on outdoor location in the Tiergarten, where the company had built an artificial wall, a replica of the real wall. Caine had worked until four in the morning, but when he came to the Drei Bären to join us for lunch, he looked great. He’s six feet two, with a good build, thick, wavy yellow hair, heavy-lidded blue eyes behind horn-rimmed glasses (he’s nearsighted) and a fair, clear skin with faint freckles sprinkled on his nose. His best features are his nose and mouth: strong, clear cut (what used to be described as “chiseled”), handsome. He was wearing a light-blue denim jacket, slacks to match, and a blue button-down shirt. (“I always wear a button-down shirt because I cannot stand those bones that go in and always get bent at the laundry if you forget to take them out, and which you never can find when you want to.”) With his coloring, that shade of blue didn’t do his looks a bit of harm.

“You won’t like him,” some friends in London had told me. “There’s this cold, Cockney arrogance.” They were wrong. He has a pride, a self-respect, that has nothing to do with vanity or conceit, and he also has implicit male authority, but he doesn’t throw his weight around. It’s his honesty that flummoxes people. He’s intelligent and truthful, a combination guaranteed disconcerting to those accustomed to the dubious twaddle that passes for conversation almost everywhere and especially in movie-star circles. He is also an innate gentleman, kind, tactful, sensitive to the thoughts and reactions of others, and with instinctive good manners and taste. It’s a little surprising, because he’s been through the mill and he knows where it’s at, but he’s not crass.

While we had lunch, we talked about the Time cover story and its ecstatic burbling about “swinging” London. Caine said it was so embarrassing that it was enough to make him turn square. “All the tourists will be coming to take a look at us and in two years we’ll get the real tail-end Charlies. Americans used to be so frightened of the rain and the boiled cabbage and the asexual men in bowler hats, but the change has been going on for some time and at last the Americans have discovered it…. They’ve discovered Turner, too. Friends used to come to London and say, ‘But where are your great English artists?,’ so I’d take them to the Tate to see the Turners. Now they’ve suddenly discovered him.... I think the years 1950 to 1980 will stand as an important era for Britain. We had a great cultural thing that started with Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth and painters like Francis Bacon. Now we have the young painters like David Hockney and stage designers like Sean Kenny and film directors like Sidney Furie, who did Ipcress, and John Schlesinger, and Kenneth MacMillan, the choreographer. The excitement of England today is everyone you meet. You meet a guy today and he’s nobody and you know he’s going to be somebody…. London used to be dull on the surface. Friends would say, ‘This city is so boring,’ and I was always angry because I had to agree with them. Well, of course, it’s still true about the drinking hours. I don’t want to see everyone stoned in the streets, but for crying out loud, if I want to get stoned, I have a right to.

“Now they’ve got these clubs like Dolly’s and The Scotch and Sibylla’s. Do I have a piece of Sibylla’s? Not me. I don’t want a piece of some discothèque that’s a fad today and then suddenly everyone starts going some other place. I put my brass in Shell Oil and A.T.&T…. All the new talent is changing the image. Americans used to think all English actors were pooves [(pronounced “pouf”): male homosexual] and they were right in a lot of cases. But not the new ones from the working class. Or take a pop singer like Tom Jones....” I said I thought Jones, who is from Wales, was the sexiest thing in Britain when he really starts to swing in a song. “That’s it,” Caine said. “That’s the way it’s going. You know, when the Profumo scandal broke, all the Americans were surprised that an Englishman was caught with a girl, but then people said, ‘Well, Profumo laid a scrubber [scrubber: prostitute] but after all he’s really Italian!’ After I played an upper-class English army officer in Zulu, the film office in London got a memo from an American film office and it said, ‘Is Michael Caine a fag?’ They showed it to me. I told them I have no need to change gears. I like to think Terry Stamp and I started the trend toward girls.”

Caine went to the men’s room and came back smiling. “Just as I’m about to walk out,” he said, “an old lady pops into the men’s toilet and says, ‘Did you wash your hands?’ Naturally, you don’t want to admit you didn’t, so you say ‘Yes’ and she says ‘Forty pfennigs.’ I can’t get used to their customs. Did you notice in the Hilton when the elevator boys say ‘Up’ they mean just the opposite? They say ‘Upp’ and they go down—to coin a phrase. Well, I guess the English have their customs, too. We rise to every situation with ‘a nice cup of tea.’ I was reading in the paper about the moors murders, and it said that after they killed that boy, the girl said she went in the kitchen and made tea and they sat around drinking it. There was another thing recently—interviews with people about what they were doing when World War II began. One man said, ‘When war was declared, I was in the garden and the wife called out and said, “The Prime Minister is on the wireless and war is declared,” and I said, “Put the kettle on and we’ll have a nice cup of tea.”’ That’s our anodyne for everything.”

We went back to the Hilton to change because we were going to a cocktail party. The party was like most parties, with everyone milling about and trying to chatter brightly. Caine mingled unobtrusively and in no way attempted to act the Star. His new leading lady, Eva Renzi, a tall, twenty-one-year-old blonde, born in Berlin of a French mother and Danish father, created much more of a stir when she swept into the room, laughing self-consciously and kissing everyone, but this was her first big film role, after a short career in modeling and television, so I guess she felt she had to live up to it. Caine let her take the spotlight and he sat quietly in a corner, talking with Guy Hamilton, the director, a dark, thin Englishman, and Charlie Kasher, the producer, a dark, chunky American. (“Kasher used to sell hair tonic,” Caine told me. “That’s right,” the press agent said. “He was a pitchman in a carny show. Then he found out about lanolin and started making stuff for the hair. He took his mother’s name, Antell, for the products and made a fortune. Then he bought an off-Broadway theatre and produced plays, and now he’s a movie producer. He produced Ipcress.”)

I told Caine he didn’t act like a star and he said maybe one reason was that he never expected to be one. “I didn’t start out to be a big star. I thought maybe I could be like Arthur Kennedy, who’s a fine actor but not the glamour-star type. I figured that would be as far as I’d get and I’d be satisfied. Anything else is a bonus to me and a complete shock. I’m having a new experience in being a movie star and I’m enjoying it—even in Berlin. I get to travel first class and free. I never thought I’d ever do it.”

Caine comes from the East End slums of London. A true Cockney is someone born within earshot of Bow bells (the bells of St. Mary-le-Bow Church in Cheapside), and that’s Caine. He was born Maurice Micklewhite on March 14, 1933, on Old Kent Road, in the East End dock area near Billingsgate fish market, where his father was a porter and his father before him. (“I come from a long line of fish porters, but I was one of those rebellious youths. I didn’t want to get up at five in the morning and carry iced fish around all day.”) He has no nostalgia for the scenes of his childhood. “We lived in a terrible Victorian brownstone house with a lot of other families. There were no bathrooms—just one toilet in the backyard for all four floors. And gas lighting. I never saw electricity till I was thirteen. During the war, I was evacuated with my mother and younger brother to a village in Norfolk, where we lived in a huge farmhouse with twelve families. When we came back to London, our house was bombed out, so then we lived in sort of a prefabricated shack. To me, that whole slum area is a hateful place. The quicker it goes, the better. People talk about the great camaraderie in the slums. Well, there was great camaraderie in the blitz, too, but that didn’t make the blitz good. People living in rotten conditions and having to cling together—if they can live in clean, decent places, I’d rather have them there.”

He started acting in school plays when he was a child during the war (“A man gave me five shillings once because I was the best one”) and later belonged to an East End youth club, where he ran the drama club, wrote plays and acted in them. He quit school at sixteen (“To be a good actor, you have to have a little fur and a little animal. Too much education is bad”) and went to work moving boxes around in a tea warehouse. (“I was always a good worker. They got their money’s worth, whatever I did.”) He’s had a lot of jobs in his day: office boy, construction hand, cement mixer, pneumatic-drill operator, dishwasher in restaurants, night clerk in a fleabag hotel in Victoria, factory worker. (“Lyons tea shops had a factory in Hammersmith where they made about 3,500,000 fruit pies a week. I worked there on the night shift: I had to get up at six p.m. and work till dawn and I hated it. I was the only white guy with two hundred West Indians. They used to call me Sanders of the River. I got along with them fine, I guess because they could see that there was one Englishman as badly off as they were.”)

At eighteen, he was drafted for National Service and spent a year in Germany and a year in Korea as an infantry private. “I was a very poor soldier. I don’t like discipline, especially from people who know less than I do, and when I went in the army, I thought I knew everything. The only way to get out was to shoot your big toe off. We used to have five cases a week in Korea—all while cleaning their guns, of course. I hated every minute of it. It’s the only business in the world where guys get less pay for being in the front line and getting killed than for repairing radios for officers in the back line. I’m not going again. If there’s another war I’ll be a medical orderly or a coal miner…. It was in Korea that I noticed heroes weren’t all six feet three, with perfectly capped teeth, but ordinary guys, so that’s the way I try to play them, not like movie stars, which I hate. I can’t stand ’em. Harry Palmer in Ipcress and Funeral, he’s not a glamorous spy. He earns twenty-four pounds a week, lives in a bed-sitter, buys his clothes off the peg and drinks beer. He’s just a guy who’s doing the best he can with his life, which is what I am.”

While this last might sound like a slight understatement, I think Caine meant it. He doesn’t dramatize himself. The key to his acting is also understatement, but beneath it lie style, authority, control. It’s not as easy as it looks. When the London Times reviewed Ipcress, the critic said, “Whether the film will do for him what the James Bond films have done for Mr. Sean Connery is doubtful: he is too good an actor for that. What he gives here is not a bland, generalized star performance, but a real actor’s interpretation of a particular man in a particular situation—and he does it superlatively well.”

It has taken years of hard work to give him this inner reservoir of professional expertise. “I spent ten years slugging my guts out in rep and on tour. I couldn’t get a part in a West End show. I must have done fifty-eight auditions and never got a job. People ask me when I’m going back to theatre. I’ve been in the theatre and I’ve played in the provinces. You name it; I’ve played it. I don’t owe the theatre anything. I tried for so long and I never made it. I got an average wage of four pounds, ten, a week in the theatre and TV. I want to bring that average up to twenty-five pounds a week, so I figure I have to earn roughly a million dollars in the next five years, which I will. All that stuff about money not making you happy is just propaganda put out by the rich. Like the religious bit about the meek inheriting the earth. I’m going to make a million—” he slanted a look at me and added, out of the corner of his mouth—“and maybe a little more.” (He will, too, and it won’t take five years because he’s halfway there already.) “When I go back to the theatre,” he went on, “I’ll put on my own plays. I won’t have to kiss anyone’s ass. I’ll buy the theatre and I’ll buy the plays. I won’t have to ask any favors. I’ll take any of them on then. I can hold my own.”

A couple of days after my arrival in Berlin, Caine and I had lunch alone at a sidewalk restaurant. (“Let’s go where we can watch the girls with low kneecaps,” he had said. “What are those?” “Those are the girls whose legs are shorter from the knee down than from the knee up. There’re a lot of them in Berlin. I find this a very an aphrodisiac city.”) Afterward, we took a two-hour walk across Berlin, while he continued to answer questions about his career.

“When I came back from Korea, I got a job in a Smithfield meat factory. I wanted to be an actor and everybody took the mickey out of me. I was desperate to find a way in. There was an old man working in the factory whose daughter was a semipro singer and she got a publication called The Stage every week, so he brought me a copy, and it had an advertisement for assistant stage manager who could also play small parts. It was a little town in Sussex, and I got the job for fifty bob a week. Mostly, I fetched tea and cigarettes for the company, but I also made my acting debut. I was usually the guy who came in at the end of the play and said, ‘Will you come with me, please?’ I was twenty. Then I got sick with malaria I had caught in Korea and I was in hospital two months. I went from 160 pounds down to 108 and that was mostly my bones and shoes. I was an emaciated six-foot-two, and I used to come on like a bottle of milk. I was so pale I was almost transparent.... I worked at any crummy job I could get, and then I got taken on by a rep theatre in Lowestoft, which is the world’s coldest seaside resort. The producer was seventy-two and an old-time actor-manager. He said to me, ‘You’ve got a hell of a long way to go, my boy, but there’s something different about you. There are about three actors who can listen on a stage, who can act as if they’re really hearing the other actors’ words, instead of just waiting to speak their own lines. You know how to do this.’ After a few months, he said, ‘I can’t teach you any more. You should go to London.’ So I went and fell flat on my face.”

Meanwhile, in 1955, he had married the Lowestoft repertory’s leading lady, a good-looking blonde named Patricia Haines. They have one child, Dominique, now nine, but the marriage didn’t work out, and they separated in less than three years. Patricia, since remarried, recently told her story to a London weekly: My Life with “Alfie”—Michael Caine’s ex-wife, Patricia, talks of their stormy marriage. Caine had just heard about it in Berlin, and he was not only upset but also genuinely shocked. “I don’t understand how she could do it,” he told me. “What really gets me is that she let a photographer take pictures of Nicky.” (Caine supports Nicky, the daughter, and visits her frequently at her school in the country. “She’s my daughter and I don’t want her to have another father. It’s confusing enough for the kid as it is.”)

According to the ex-Mrs. Caine’s story, the tone of which is a bitter one (she does not have a single good word to say for Caine), the failure of the marriage was entirely his fault. The substance of her plaint is that he kept trying to make it as an actor and wouldn’t give up, which she apparently thought he should do. “We were lucky if we made three hundred pounds a year, together,” she is quoted as saying. “I can’t remember one single moment that was happy…. There weren’t any good times.” She even vitiates her admission of Caine’s present generosity by adding, “Now he wants to make amends. There’s nothing like a few thousand quid in the bank... to bring a man out.” (Caine’s reaction to her version, when questioned by the same writer, was a gallant one. “Honestly, I think Patsy’s a fine woman,” he said. “I always did. I got married too young.”)

About the same time the marriage broke up, Caine’s father died. “I really touched bottom. My acting career was all fouled up, and I didn’t have the courage to face anyone. I’d lost my nerve. I went to Paris with twenty-five pounds, which was my father’s insurance policy. I used to eat one meal a day at the air terminal, where an American student on the night shift would give me free coffee and sandwiches. I’d sleep on chairs in the terminal and wake up in the morning and try to look as if I were going to catch a plane…. Then, one day, I thought, ‘Okay. I’m ready to start again.’ I’d saved my return ticket to London, and I went back.”

He was working in a laundry when he got his first film job. (“That laundry was one of the great intellectual periods of my life: I used to read two books a night.”) He made about thirty-five films in which all he said was, “You’re under arrest,” or “Dinner is served.” He played rep in the provinces, and he did a hundred twenty-five TV plays. (“I was nominated four years running for TV Actor of the Year and never won it. I’d love to win an award.”) He was O’Toole’s understudy in The Long and The Short and The Talland replaced him in it for a six-month road tour…. Recalling those long years of tenure on the treadmill, he is touchy about any implication that his present success is a facile one. “I feel vitriolic toward people who say I’m just in films for the money alone. I’ve gone out on a limb where I could have got smashed to smithereens. I’ve never taken the safe way out. Playing Harry Palmer, a spy with glasses—or Alfie, a guy who gets a nice married woman pregnant—that’s not guaranteed sympathy at the box office. I’ve never sold myself down the river for money and I never will…. Six actors have turned down every part I’ve had. I was never handed a script without fingerprints on it.”

The final breakthrough came with Harry Saltzman. Friends had recommended to Saltzman that he watch Caine in a TV play. He liked what he saw. He went to see Zulu to find out how Caine came across on a screen, and, as he delicately put it to Caine later, “You look like a man with three balls.” There were no involved negotiations. Caine was sitting in the Pickwick with friends when Saltzman came into the restaurant and saw him, called over Wolf Mankowitz, the writer, who is one of the owners of the Pickwick, and asked him to introduce Caine. “I went over to Saltzman’s table,” Caine told me, “and he said, ‘Do you want a drink?’ and I said ‘Yes’ and before the drink came I had accepted the part in Ipcress and also agreed to do two pictures a year for five years, and by that time my drink came and I took it and walked back to my own table.”

After Ipcress, he did The Wrong Box for Columbia, a farce with Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Peter Sellers, Tony Hancock, John Mills and Sir Ralph Richardson (“The people I really like are people like Richardson. Did you know he collects antique clocks?”) and Alfie for Paramount, the saga of a lecherous, boastful, young Cockney bed-hopper. It got great reviews in London (“rich, ripe, randy portrait... a ribald parody of our times”) and a special award at the Cannes Film Festival, which so infuriated the French critics that they wrote a joint letter suggesting a “vulgarity award” for the jury. “The French have always been prudish,” Caine said, “but with Mme. de Gaulle they’re worse. They hated the abortion scene. It was too strong and too real for them.”

Originally, Caine was supposed to play a nude scene with Shirley Anne Field, but he made them drop it. “It was phony,” he told me. “Here we were, supposed to be alone in a room, and she sits up in bed and holds the sheet in front of her. I told them, ‘We’re not making a movie for voyeurs. We’re doing a realism film, not a striptease.’ I did Alfie because I think it has a valid moral statement to make. I don’t know how it will go in America, but of course I’m glad it was a smash in London. After the opening, we had the swingingest party at a pub called The Cockney Pride, with faggots and bubble-and-squeak and all the booze you could drink.” “Faggots!?” I said. “Squares of meat.” “Oh. And what is bubble-and-squeak, anyway?” “Cabbage and baked potato, left over and then fried—a heart attack in every bite but it’s lovely. Americans are so hung up on cholesterol but Cockneys thrive on it.”

For the American release, Caine dubbed fifty-six loops into more comprehensible English. I asked him to give me some examples of the changes. “Well, for one, there’s the word ‘fag,’ which a Cockney always uses for a cigarette. In the scene where I’m examined for TB, the woman doctor says, ‘Do you cough much?’ and I say, ‘Only after the first fag in the morning, but doesn’t everyone?’ We changed ‘fag’ to ‘smoke.’ Mostly, though, it was a matter of pronunciation. For example, in the sanitarium, I’m talking to the guy about visitors and I say something like, ‘I’ve seen ’em comin’, bringin’ their fruit and candy, and then they go out and they’re thinkin’, ‘Keep them insurance payments and don’t throw that black hat away.’ The way I say it in a Cockney accent, it sounds like ‘black cat’ and Americans would think, ‘You keep a black cat for funerals. Is that one of your English superstitions?’”

Caine usually talks with sort of a modified Cockney accent. The famous Cockney rhyming slang is a language invented so Cockneys can talk dirty in front of their mothers and wives. “Cockneys don’t use bad language in front of women,” Caine told me. “They may if they’re angry, but not in conversation. My mother doesn’t understand Cockney slang, it’s also used by criminals—a lot of criminals are Cockneys—but young Cockneys like me don’t bother with it much.” I told him I had read that when Jean Shrimpton started going with Caine’s best friend, Terry Stamp, who is also a Cockney, she learned the accent and slang the way she would a foreign language. “You could learn two foreign languages instead,” Caine said. He gave me an impromptu trial lesson in his trailer on the set one night. The accent is similar to Australian, but perhaps not quite so nasal. In the rhyming slang, they use the first of a pair of words, the second of which rhymes with the word they really mean. Thus, “Gawd, look at them plates!” means “look at those feet,” because in “plates of meat,” meat rhymes with feet. “Get up them apples” means “Go up the stairs,” from “apples and pears.” “I’ve just had a terrible bull with the trouble”: bull and cow equals row; trouble and strife equals wife. If a man comes in with a girl, you can say, “Who’s the ice cream?” Ice-cream freezer rhymes with geezer, and a geezer means a fellow who’s a stranger.

For the nimbler minded, there are more complicated variations. “Get off your aris” means “get off your ass,” because aris comes from Aristotle; totle rhymes with bottle; and a bottle is made of glass. This is more devious than just saying “Get off your Khyber,” which comes from Khyber Pass. Another form is to reverse the letters, so that a bird becomes a drib and a boy a yob, as in “He’s one of our yobs.” Spiv, a Cockney word for gangster, is simply V.I.P.s backward, with the meaning also reversed.

One of the results of Alfie is that Caine has been publicized as an Alfie in real life—a dab hand with the dribs, as Alfie might say. He’s always being photographed with dishy girls, and British interviews with him have stressed an energetic and omnivorous sex life. (“I don’t believe in waste. When there are plenty of birds around, why waste them?” “It’s not difficult meeting birds. After all, girls will go out with a short fat man with money so why wouldn’t they go out with a tall thin one? ’Course you don’t know whether a bird’s out with you because of who you are—but who cares? It’s not too unpleasant sorting the wheat from the chaff.”) I asked him about this, and he bridled a bit. “Reporters come with a preconceived idea of what they’re going to write,” he said. “I talk about books and painting and acting, and then they ask me about birds and I make some silly remark and that’s their story.” Actually, his attitude toward women is rather a romantic one. “I have to feel a real affection for a girl. I couldn’t fall in love with a bitch. A bitch is a woman that tramples on other women and wants to dominate men. I have a Victorian attitude toward women. I’m in charge. I’m the guvnor. They don’t have to make decisions or arrangements or pay for anything—none of that ‘I’ll pay half of the dinner.’ I like completely feminine women. I don’t wish to date a female President of the United States or a female bank president. The only advantage in dating a female bank president would be she could get to work late in the morning…. I’m not Alfie. I don’t go for the one-night-stand thing or a different girl every week. There’s no real sex in that, and no affection, either. I have to feel affection.” I asked him if he thought he would marry again and he said, “Definitely! Without a shadow of a doubt. But I would want to marry a woman who would be a mother to my children, not to me. I’m not looking for any mother substitute.”

The girls he chooses are mostly young models and actresses. “I’ve had scrubbers in my time, but now I want beautiful girls with class. As a young man, I never did make it with a Cockney girl. If you go out with a Cockney girl you always find out she’s got six brothers and a large father and has to be in by ten. I go with actresses and models because they’re the best-looking birds and they can travel with you and they’ve got a lot of freedom. But to tell you the truth, now it’s harder. They all think, ‘Oh, he’s so-and-so and he’s getting it everywhere, and it’s not….’” His voice trailed off and he gave me a wry look. “Well,” he said, “let’s just say that I spend a lot of time at home matching TV.”

I think that last statement night be debatable. He certainly didn’t spend any time that way in Hollywood, where he went last winter to make Gambit for Universal (in which he plays a con man who impersonates an English lord) with Shirley MacLaine. According to all accounts, he was the toast of the town. Shirley gave a party for him at The Other Place, and Howard Kotch, a Paramount executive, threw a big wingding for him in the ballroom of the Beverly Wilshire, with seven hundred fifty guests. He spent New Year’s Eve at Pamela Mason’s bash, and he was one of the chosen few who ate Chinese food with Prince Philip in Danny Kaye’s kitchen one late, late night. He danced his head off at Daisy, Beverly Hills’ best discothèque; and Frank Sinatra flew him to Las Vegas in his private plane for a weekend. He was quoted as saying of the whole period, “I had a ball. I was stoned a lot. I went everywhere and met everyone. They all treated me great and I really swung.” Doesn’t sound as if he spent many evenings watching Perry Mason.

I talked by telephone with Leo Fuchs in California. Fuchs is a bright, perceptive young man who produced Gambit and who chose Caine for the role after seeing Ipcress. “He went out with every girl in town,” Fuchs said. “He’s just about the coolest when it comes to women. He’s the kind of a guy that walks into a party, goes up to a bar, has a drink and just stands there and waits for the girls to come to him. He knows they’ll come. And he never moves from there.”

In London, Caine lives in a mews house in the Marble Arch section. It is decorated in masculine style: navy, brown and beige color scheme, solid furniture of leather and teak and unvarnished wood, tweedy curtains, walls covered with Japanese grass paper and Hessian cloth. He has a seven-foot bed, records for every mood (“I have moods, like everybody”) and about forty paintings, mostly by young British artists, among whom are Frank Auerbach, John Piper, Paul Nash, Jack Taylor. When in town, he goes to a lot of art galleries and is surprisingly knowledgeable about painting. In Berlin, I mentioned George Grosz and Caine said: “I know who he is. I saw an exhibition of his work in London.” He also reads a lot.

He’s not going to be able to spend much time at home from here on. After all the years of hitting his head against a wall, now everyone wants him for a film. When he finished Funeral in Berlin, he flew to Louisiana last June to star in Hurry Sundown for Otto Preminger. In this, he plays a Georgia farmer (“I’m this guy who didn’t go to war and made money while the other fellows were away”) and in Berlin he was practicing a Southern accent with the help of tapes Preminger had sent him. (If he can pull this off, he can do anything.) Then he starts Billion Dollar Brain (another Len Deighton, for which Saltzman paid a reputed $250,000) in Helsinki. “I know what I’m doing until 1968,” he told me. “After Brain I do Deadfall, sort of a Maltese Falcon set in Spain, with Bryan Forbes directing. Then comes The Magus, from John Fowles’ book, and Horse under Water, an earlier Deighton book about heroin.”

“He’s going to be one of the biggest stars the business has ever known,” Leo Fuchs told me. “He has that rare quality that is not just personality, but whatever it takes to make people remember him. He’s a hell of a talented actor on top of that. He’s got everything going for him—and he’s a nice guy.”

Caine is walking proof that to be cool you don’t have to be snotty or alienate yourself right out of humanity. He has a quiet quality of unassailable poise that makes other men appear gauche and immature, whatever their age. In Berlin, George Segal, who was also making a film there, came to visit the set of Funeral. Although only a few years younger than Caine, he seemed very boyish, in comparison. It’s the same with older men. We sat in the trailer one night, drinking and talking—Caine, myself, the director, the producer, two British army officers, an assistant director and two production men. Caine stood out from all the others, not because he is good-looking or because he was the star, but because he is a man who knows who he is and so he doesn’t have to put on an act to mask inadequacy. He didn’t just sit there, ordering people around, Hollywood style. He got drinks for everyone (“The booze is flowing like glue around here,” he said), opened beer cans, and joined in the conversation instead of monopolizing it. Nobody treats him like a flunky, but the important thing is that he doesn’t treat anybody else like one. He respects himself, and thus he can afford the luxury of respecting others.

You Might Also Like