The Auteurs of San Quentin

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Like many independent filmmakers, Anthony Gomez has some quibbles with his own work. He wishes he’d had more time to shoot. His lead looks natural on camera but the voiceover delivery is stiff. A friend came through with some original music, but the post process was crazy. The usual stuff. What’s unusual is that Gomez, 26, made his most recent film, a short documentary about working out, while living inside San Quentin State Prison.

“It’s the first time I’ve had my parents say they’re proud of me since I graduated from high school,” Gomez says of the videos he has directed, starred in and contributed to while inside San Quentin. Among the highlights is a series of mockumentary shorts inspired by The Office. Staring deadpan into the camera after the guy next to you says something stupid, it turns out, is a cinematic language that translates to workplaces everywhere.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Gomez is one of five incarcerated men who work at ForwardThis Productions, the first film and TV production job training program located inside an American prison. Life in San Quentin is a Spartan existence, but one of the few things the men here have in abundance is stories. Gomez grew up in a small town outside Fresno and planned to join the Navy and marry his high school sweetheart. When he was 18, he drove the getaway to and from a murder (his now ex-friend was the shooter). He is now seven years into a 21-year sentence for voluntary manslaughter. “We all appreciate being in a position to tell stories about ourselves,” Gomez says. “I do matter.”

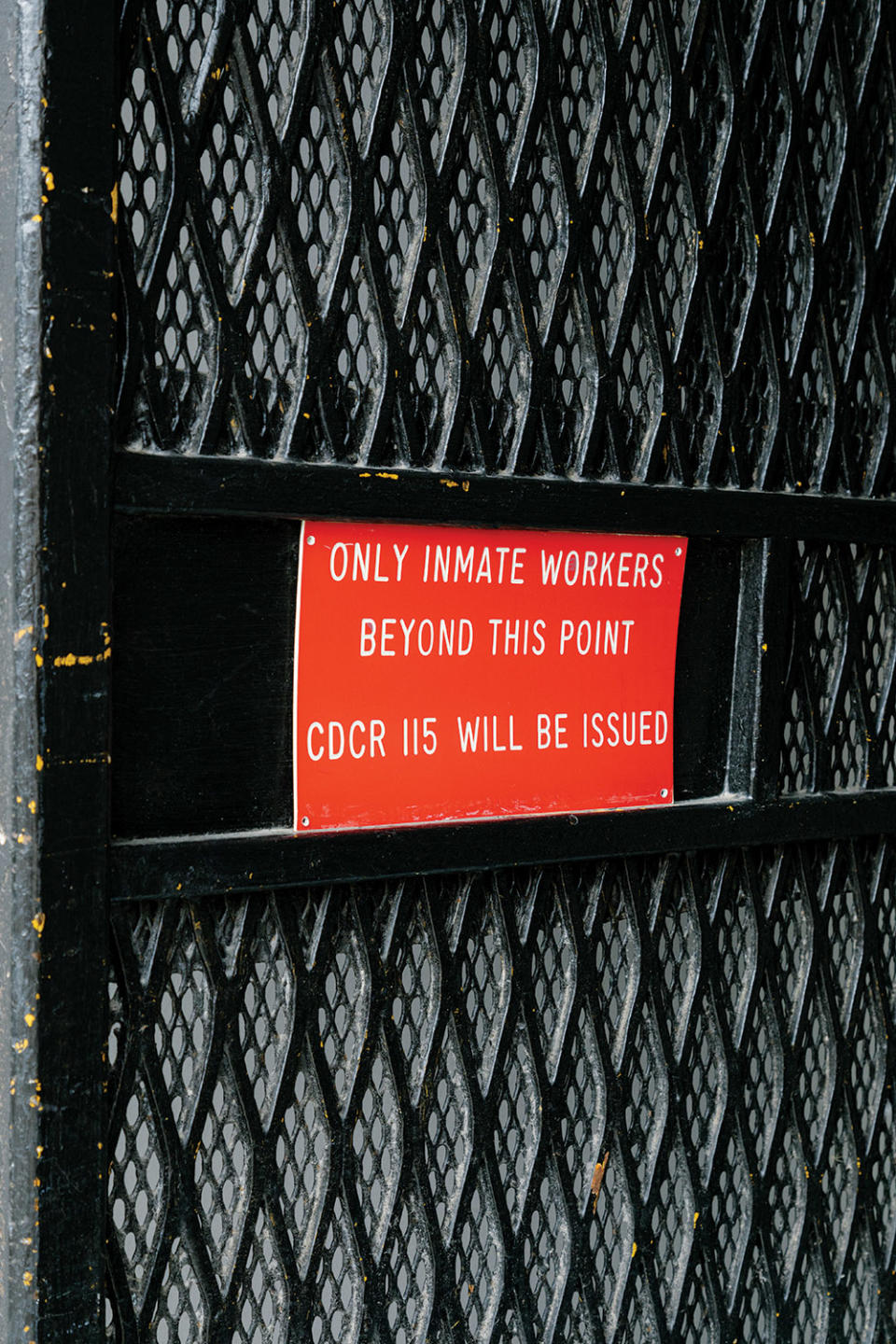

ForwardThis opened in late 2021 inside San Quentin’s media center, a burgeoning content empire staffed by incarcerated people that also produces a newspaper, The San Quentin News, website and the podcasts Ear Hustle, a Pulitzer Prize finalist, and Uncuffed. The prison’s public information officer, Lt. Guim’Mara Berry, must approve all the content before it goes out to the general public. ForwardThis is housed in a tiny office behind the newsroom, with four Macs, lockers storing cameras and lenses, and a shelf of filmmaking books including Story by Robert McKee and The Shut Up and Shoot Documentary Guide.

Despite its location — behind barbed wire, past guard towers and through the yard at the oldest and most notorious prison in California — ForwardThis has been attracting some noteworthy visitors. In March, California Gov. Gavin Newsom came to the Marin County prison to announce that he was allocating $20 million in the state’s budget to transform San Quentin, which houses the largest death row in the U.S., into a rehabilitation center modeled on prisons in Norway. ForwardThis predates Newsom’s plans and draws its funding from individual donors and foundation grants, not the state, but the initiative exemplifies the model the governor is advocating, which emphasizes job training and other programming designed to disrupt the cycle of recidivism. In the U.S., almost 44 percent of released prisoners are back behind bars within their first year out, with inadequate job skills and social stigmatization as key contributors to the problem.

The ForwardThis program’s goals are to help tackle those issues, via employment training and image-shaping. “We want to create a pipeline to get people jobs in the industry and second-chance opportunities, and we want to see the lived experience of incarcerated people represented,” says Jesse Vasquez, executive director of the Pollen Initiative, the nonprofit organization that backs ForwardThis and The San Quentin News. Vasquez, 40, paroled out of San Quentin in 2019 after spending nearly 20 years incarcerated for a drive-by shooting when he was 17. “It makes people reconsider their views on the system when they see these guys. Your worst act doesn’t have to define you for the rest of your life.”

Over the next several months, the Pollen Initiative plans to open multimedia programs like ForwardThis and The San Quentin News at three other prisons: the Central California Women’s Facility in Chowchilla and two North Carolina prisons, one for men and one for women. The organization, which is transitioning from it previous name, Friends of San Quentin News, had a budget of $480,000 in 2022 that will increase to $750,000 this year to sustain its growth.

ForwardThis has been building its relationships with Hollywood with the help of Hangover producer Scott Budnick, the founder of the Anti-Recidivism Coalition, a nonprofit that advocates for criminal justice reform. Budnick has recruited industry figures to join the room by Zoom to talk about their crafts, including Narcos creator José Padilha, Booksmart writer Susanna Fogel, Joker editor Jeff Groth, TikTok creator Vic Blends and even Kim Kardashian, who led a discussion about shortform content from her car after dropping her kids off at school. “You can see how life-changing this experience is for these men,” says Budnick, whose organization has helped place some 200 formerly incarcerated people in industry internships and jobs with employers including NBCUniversal, DreamWorks Animation and Endeavor. Of whether Hollywood will eventually hire the ForwardThis grads, Budnick says: “No one cares [that they’ve been incarcerated]. Show up early. Work your ass off.”

Men living inside San Quentin don’t have access to the internet and social media, but once the prison’s public information officer clears the videos they make in ForwardThis, volunteers share the content on YouTube and Instagram. The audience so far is modest, with viewership typically in the hundreds. The most watched video on their YouTube channel is a three-minute romance about a married couple’s visiting schedule, directed by Jeremy Strain. Strain, 38, was in and out of juvenile detention centers beginning at age 14. He has been incarcerated for the past 17 years for aggravated mayhem and assault, and has lived in nine different prisons in California. “I came up with the concept of a story about visits because that is the heart of the rehabilitation process,” says Strain, whose wife, whom he met through a pen-pal program while in prison, and stepson visit him at San Quentin every weekend. “It’s like a reset button to get me through the week,” he says of the visits.

After a childhood in Sacramento that he describes as “dysfunctional, abusive, lots of drugs and alcohol,” Strain entered the criminal justice system convinced his best shot at survival was hiding any vulnerability. He had dropped out of school in seventh grade and been addicted to opioids and alcohol. “I was on guard all the time, trusted no one and created an alter ego of this raging, angry person in hopes that I’d be left alone.” In 2009, after a violent fight with his cellmate, he spent 14 months in a segregated housing unit (SHU), commonly referred to as solitary confinement. On Strain’s first day on the yard after leaving the SHU, he witnessed a stabbing. In that moment, Strain says, he thought to himself, “I know this is not who I am. No way do I want to live my life like this.” He began taking advantage of therapeutic tools available in prison, including Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, victim impact and anger management programs. He also went back to school and is now in college, with more than half the units needed to earn an associate’s degree in social behavioral science. Though he was given a life sentence, Strain will soon be going to the parole board, and if he ever does leave prison, he hopes to pursue a career in editing. “To me, editing is digital art,” Strain says. “I’m a quick learner and ambitious.”

The men in ForwardThis are an elite group among the more than 3,000 who live in San Quentin, singled out for their good behavior and potential. Apart from working out and eating, they spend most of their waking hours — from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. Monday through Friday — in the relative tranquility of the small production office, working on their films or studying. “It’s a privilege,” says Gomez. “Not everyone is afforded the opportunity to hold cameras. There are not a lot of people on the yard who know what we do. We can’t be getting involved with nonsense.”

From a cinematography standpoint, their environment is limiting. “It gets pretty redundant,” says Ryan Pagan, 35, who has been in prison since he was 19. “If you’re going to go for that ‘We’re in prison’ look, we’ve definitely got that. Barbed wire, we got it. Bars, we got it.” Among their favorite places to shoot is the prison chapel garden, largely because there are flowers. Pagan is interested in learning more about animation, in part because it would expand the scope of his storytelling.

One advantage the ForwardThis men feel they have over people on the outside who make films and TV shows set inside prisons, however, is firsthand experience. Says Marcus Eugene, 26, who made a film about gangs, “We live with the subjects of our films. At the end of the day, we’re all going back to West Block.” To many of the men here, pop culture depictions of prison life are offensive at worst and laughable at best. Jokes about prison rape? Not funny, they say. One-dimensional thug characters? Way less interesting than the real people who live here. “Everyone has this perception about what incarcerated people look like,” Pagan says. “It’s easy to sensationalize. People are drawn to violence. It’s like we’re all just animals. In my experience, people who are incarcerated have a higher emotional IQ than the rest of society. We have to.”

Pagan grew up in what he calls a “turbulent” middle-class family in Riverside, wanting to be an actor. His father, a merchant marine, was often away and his mother, an immigrant from Belize, had trouble adapting to life in the States. “My mindset of not wanting to listen to anyone in authority made it easier for me to hang out with not-so-good people,” Pagan says. In 2007, he shot and killed a man during a bar fight and was sentenced to 77 years to life. In 2021, he was transferred to San Quentin from California’s High Desert State Prison, where he had worked in an HVAC training program, and he heard about ForwardThis. “Coming here and seeing my peers with cameras made me curious,” says Pagan. “Here they were, creating something for the world to see. I already had a passion for film. When I saw the stuff they were doing, it lit that fire. It reminded me of what I wanted to be when I was young, before I went down the road I went down.”

Pagan directed a short satire about job hunting in prison, which also tells a story about the perception of young Latino males. One angle, shot from behind Pagan, shows him as he looks and sounds — wearing a blue button-down shirt, hair cropped in a tidy fade, straight posture, soft-spoken — while he tries to find a job at San Quentin. Other jobs open to Pagan include teacher’s aide, housing clerk and janitor. The reverse angle shows how Pagan thinks others see him — in a white undershirt and beanie, walking with a gangster’s exaggerated lean, looking for something to steal. In the film, various potential prison job sites turn him away, until he gets to the ForwardThis door, where Pagan looks like himself in both camera angles. “Hopefully you guys see me for who I am,” he says in the video. The film helped cement Pagan’s place in ForwardThis, where he now takes a leadership role. When high-profile visitors like the governor come to visit, he’s the one who makes the presentation. Pagan, who will go to the parole board in six to seven years, has met the governor twice. “I think I made an impression on him,” he says.

This story appears in the July 26 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Eight Actors Who Have Played Willy Wonka in Films and on Broadway

Martin Scorsese’s 10 Best Movies Ranked, Including 'Killers of the Flower Moon'