Assassinated 50 Years Ago, How Martin Luther King's Activist Spirit Lives on in His Hometown Church

If the walls of Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church could talk, this is what they might say:

They might tell of Adam Daniel Williams, who during his 25-year tenure as senior pastor helped found the Atlanta chapter of the NAACP.

They might recall Williams’ son-in-law, Martin Luther King Sr., as he appealed to hope throughout the Great Depression.

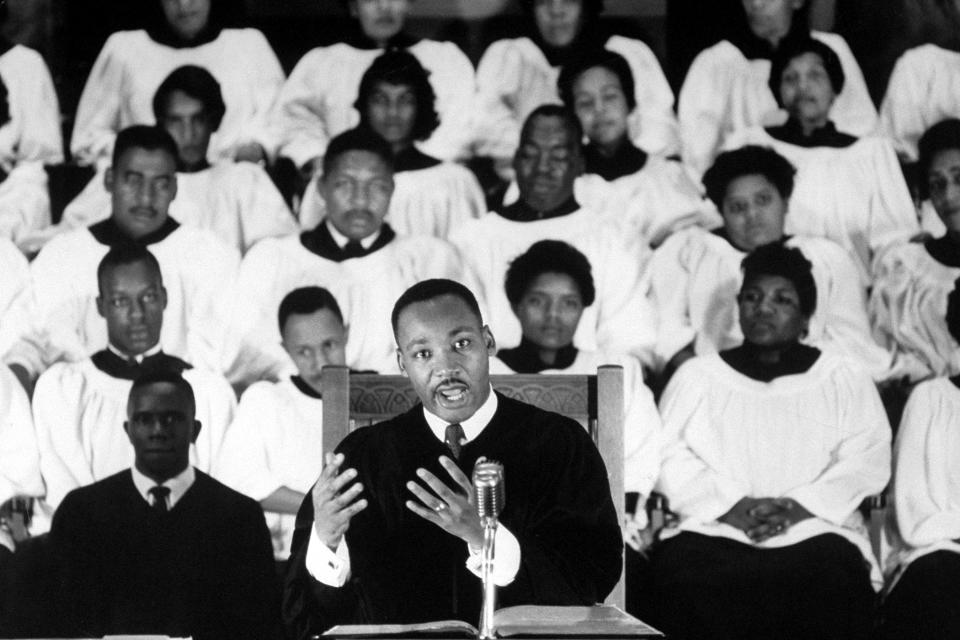

And they might boast of a small boy who stood on a milk carton to sing in church choir — the same boy who grew up to be Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., standing on the shoulders of his predecessors to emerge as America’s preeminent figure in the ongoing fight for racial equality.

Today, some 50 years after King was assassinated in 1968, the activist spirit at Ebenezer Baptist Church that launched him into greatness lives on. Rev. Raphael Gamaliel Warnock, the fifth and youngest senior pastor in the church’s history, has spent his last 14 years at the helm, mobilizing residents of all ages and beliefs.

“Martin Luther King Jr. was a spiritual genius, a social change agent and part of the black church tradition,” Warnock tells PEOPLE ahead of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, commemorating King’s birth.

Says Warnock: “I stand in the long legacy of trying to continue that work.”

RELATED: Coretta Scott King Was ‘Architect’ of Husband Martin Luther King Jr.’s Legacy, Daughter Says

Since he became senior pastor in 2005, the congregation has more than doubled in size — now surpassing 4,000 members. The reverend attributes part of that growth to their ability to attract millennials through civic activism, recruiting even those who “are naturally suspicious of institutions, including the church,” he says.

As part of their service-oriented action, Warnock has led his community in a years-long effort to clear arrest records of Atlantans, allowing them access to employment and housing opportunities.

In October 2016, Ebenezer partnered with Fulton County leaders to host the county’s first ever “Record Restriction Summit” where 75 percent of attendees had one or all of their arrests cleared, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported. Ever since, the reverend has increased his involvement with the criminal justice system.

Last Father’s Day weekend, he led a group that provided bail for people awaiting trial.

“We are a politically progressive church,” Warnock says. “And I don’t mean partisan politics, but what public policy ought to look like for the disenfranchised.”

Next summer, Warnock is partnering with Auburn Seminary and The Temple, among other groups, to launch a nationwide interfaith response to mass incarceration. From June 17 to 19, hundreds will gather in Atlanta to learn about expungement and form a “strategic legislative agenda at local, state and national levels” to address mass incarceration, Auburn Seminary’s website reads.

“I see this as the most obvious body of work that is an extension of Dr. King’s work,” Warnock explains. “The tragic irony of the moment is that all the forms of discrimination that Dr. King fought and died to dismantle are inscribed 50 years later within the context of the criminal justice system.”

RELATED: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Daughter Shares Advice for Resisting President Trump

According to Michael Eric Dyson — a professor of sociology at Georgetown University and author of I May Not Get There With You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr. — Warnock is carrying on King’s legacy through more than activism.

King’s leadership was founded not only on emotion and service but also grew from his education at Morehouse College in Atlanta.

“His father’s variety of preaching was deeply emotional, and Martin Luther King Jr. was a far cooler customer,” Dyson tells PEOPLE. “He was quite suspicious of religious belief and practices in the black church until he went to college at 15.”

At Morehouse, King discovered that “you could be intellectually respectable and a preacher at the same time,” Dyson says, adding that King’s greatness partly evolved from his ability to call on both his intellectual rigor and spirituality.

Similarly, Warnock graduated from Morehouse and earned a master’s degree in divinity from Union Theological Seminary in New York City. He later received both a master of philosophy and a PhD.

“The present minister there upholds nobly and ably a learned, erudite pastorate,” Dyson says. “That church continues to be a beacon to those who look toward the black church for leadership.”

In honor of Martin Luther King Day, Warnock plans to spread that light beyond his congregation of thousands.

He has put out an “all call beyond normal volunteers” for Atlanta residents to honor the late reverend by feeding the homeless and the hungry.

“It’s an opportunity,” he says, “to do the work that we are always doing.”