Artist captures multiple views and moods of Frida Kahlo in new exhibit

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Some artists are icons. Frida Kahlo is one of them. Her iconic status is both a blessing and a curse.

Icons are visual shorthand, necessarily oversimplified. The heart, thumbs-up and smiley face emojis are also icons. Kahlo’s iconography reduces her to “that Mexican female painter who was married to artist Diego Rivera, liked monkeys, and had a unibrow and a hint of a moustache.” That’s true as far as it goes. But Kahlo was far more than that.

While Kahlo was eclipsed by her famous husband in her time – she died in 1954 at 47 – she casts a very long shadow in our time. In many ways, she was ahead of her time. Kahlo fought against conformity and political repression, fought for a feminist future, colored outside gender and genre lines, and created with tireless energy, despite a childhood bout with polio and a shattering streetcar accident that left her limping and in pain for the rest of her life.

Beck Lane reminds us of this artist’s depths in her "55 Frida Project.” She based this series of mixed-media paintings on monochromatic photos of Frida Kahlo in the public domain. 17 portraits from that series are now on view at the Unitarian Universalist Church.

The idea for the series came to Lane when a Fort Lauderdale gallery owner suggested he could sell more of her work if she made it more upbeat and colorful. The idea didn’t put a smile on her face – at least at first. Then it hit her. A series revolving around Frida Kahlo would be illuminating indeed.

“I often work from photographs,” she says. “And there are about 5,000 photos of Frida Kahlo available in the public domain. She’s a woman that everyone and anyone can see themselves in. That’s what I strive for in the figures I paint., And that’s how this series got started.”

Lane’s initial online research into Frida Kahlo didn’t make her smile either.

“I started looking for photographs and trying to find more stories about her,” she says. “I’d go to Google and type in ‘Frida Kahlo,’ and all this cutesy, predictable artwork would pop up. Products based on her and so on. I kept seeing the same things: the mustache, the eyebrows, and the flower in her hair. When people see these images, they’re not really seeing this woman. I want them to see Frida Kahlo in my art. And that’s what I tried to do in this series.”

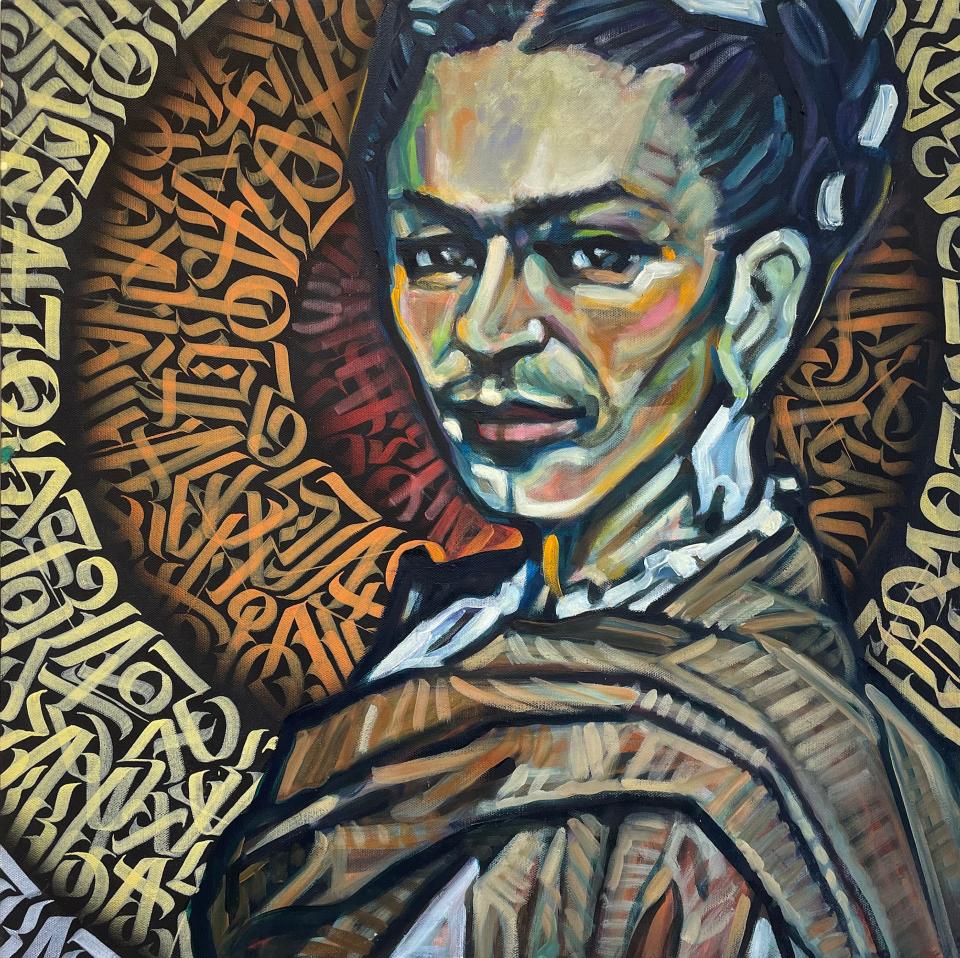

Lane’s portraits don’t imitate Kahlo’s style. Her expressionistic method defines Kahlo’s figures with contours of bold, black brushstrokes surrounding fractured facets of unearthly colors. Albert Weisgerber is the closest comparison that comes to mind – but Lane’s approach is sui generis and hard to describe. Even the artist struggles to find the words. “My friend Bill Lane (no relation) said, ‘You’re the love child of a Soviet graffiti artist and Vincent Van Gogh.’ I can’t improve on that!”

Lane’s method is also hard to pin down. She doesn’t try to pigeonhole the subject of this series, either. She’s aware of the cult of personality surrounding Kahlo. But refuses to color inside the obvious lines.

Lane’s “Frida Kahlo No. 14” is probably the most iconographic portrait here. (It actually looks like a religious icon of a saint from the Catholic or Orthodox tradition.) The artist’s head is turned in a ¾ view, but she looks you straight in the eye. Kahlo’s image is surrounded by a circular nimbus, like a saint’s halo. Look closer, and you see it’s a swirling spiral of Arabic letterforms. The calligraphic hagiography in the background is the collaborative creation of Mark Wiseman (aka “”FNMNTLS”).

The text has no translation. It’s form without content and slyly deconstructs the artist’s implied sainthood. This icon is secretly iconoclastic.

“Frida Kahlo No. 7” is a portrait of a bored artist. She's leaning against a wall, eyes downcast, a cigarette in her left hand. Not a flattering portrait – and the perfect portrait of someone who hated flattery. (You imagine her telling the photographer, “No, I won’t smile. Hurry up and take the damn picture!”) Kahlo didn’t care about her image. Lane’s painting nicely captures her indifference.

One of Kahlo’s famous spider monkeys gets into the picture in “Frida Kahlo No. 12.” In Mexican folklore, monkeys are typically wild and oversexed. This little guy is friendly and gentle. According to Lane, Kahlo kept lots of his brothers, sisters and cousins as pets at her Blue House in Coyoacán, Mexico. “Because of that god-awful accident, Frida couldn’t have children and went through lots of miscarriages when she tried,” Lane says. “The monkeys symbolized the children she could never have.”

These three paintings are all very different. They all are. In this series, any sample is a skewed sample. Lane’s portraits of Kahlo are all over the place.

In most paintings, Kahlo wears the no-nonsense clothing of Mexico’s working class. In “Frida Kahlo No. 5,” Kahlo sports a Rudolph Valentino haircut and a man’s three-piece suit. In “Frida Kahlo No. 16,” she wears her first communion dress. In “Frida Kahlo No. 11,” she hides her face with her hands. In some portraits, she stares directly into the camera; in others, her eyes are looking away. Kahlo spurned her era’s conventions of femininity. She never tried to be pretty. She always tried to be real.

Arts Newsletter: Sign up to receive the latest news on the Sarasota area arts scene every Monday.

Through Sept. 17: Sarasota illustrator John Pirman gets career retrospective with Selby Gardens exhibit

Kahlo’s indifference to branding could be a form of branding, of course. Kahlo’s peasant garb might equate to Kurt Cobain’s ripped jeans and old t-shirts. But I don’t think so. I think she just didn’t care about what people thought about her.

Kahlo was a chameleon, with no fixed form to capture. Lane tried to capture her soul instead. That’s what you see — and feel – when you look into Kahlo’s eyes in her paintings.

Lane agrees that Kahlo’s eyes are windows to her soul.

“Frida’s eyes expressed the value that she knew she had,” Lane says. “She knew her worth, when the world around her didn’t. She was just waiting for the rest of us to catch up.”

'55 Frida Project’

Runs through Aug. 14 at Unitarian Universalist Church, Lexow Gallery, 3975 Fruitville Road, Sarasota. 941-371-4974; uucsarasota.com/art-gallery-in-lexow-wing

This article originally appeared on Sarasota Herald-Tribune: Artist captures multiple portraits of Frida Kahlo in new exhibit