Ariana Grande Sued Forever 21 for Using Her Likeness. What Exactly Does That Mean?

Ariana Grande didn’t ask for permission before interpolating “My Favorite Things” from The Sound of Music in “7 rings.” And she may have paid a price for it: 90 percent of the royalties to Rodgers and Hammerstein. Grande’s team reportedly took the already-finished song to Concord, the company that owns the legendary Broadway duo’s catalog, just weeks before its January release. As Grande sings in the consumption-as-empowerment hit, “I want it, I got it.”

Now Forever 21 is in a similar predicament—with Grande in the position to potentially benefit. Earlier this week, the pop star filed a $10 million lawsuit against the fast-fashion retailer in a Los Angeles federal court. Represented by lawyer Daniel Petrocelli (of O.J. Simpson civil-case fame), Grande claims that Forever 21 posted at least 30 unauthorized images and videos across its website and social media platforms, using her name, likeness, and music, after Grande turned down an endorsement deal.

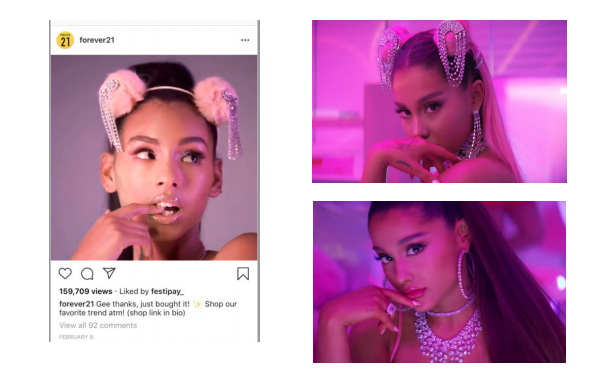

Grande’s objections include Instagram images of a lookalike model allegedly based on the “7 rings” video. In screenshots included in the complaint, Forever 21’s model can be seen donning fluffy, pink pom-poms in her hair, as well as purple camo pants and white socks in another look—all similar to Grande’s various outfits in the clip. Some of Forever 21’s posts used captions that quoted the lyrics to “7 rings,” while certain video clips outright featured the song, the complaint asserts. (The posts have since been taken down.)

Intellectual property lawyers tell me Grande has a strong case and will probably win a settlement. And they say that, as the music industry increasingly looks for money outside of selling or streaming music, these types of legal fights could affect more and more artists. “This is the future of the music business,” says Ken Abdo, an entertainment lawyer who was involved in the dispute over Prince’s estate.

Forever 21 hasn’t answered the lawsuit yet in court, but its public response strikes a conciliatory tone. “Forever 21 does not comment on pending litigation as per company policy,” the company said in a statement. “That said, while we dispute the allegations, we are huge supporters of Ariana Grande and have worked with her licensing company over the past two years. We are hopeful that we will find a mutually agreeable resolution and can continue to work together in the future.”

According to Grande’s lawsuit, Forever 21 contacted her representatives ahead of her February album thank u, next. “Notably, the endorsement deal Forever 21 sought with Ms. Grande centered around social media marketing, including, but not limited to, Twitter posts, Instagram posts, and Instagram stories,” the complaint reads. Grande claims that the amounts Forever 21 offered were “insufficient for an artist of her stature,” and that, “Rather than pay for that right as the law requires, [Forever 21] simply stole it.”

Although the case centers around social media, Grande’s strongest legal precedent is from decades ago, involving a different mass medium. California has a right of publicity law, which basically means you can’t use a person’s “likeness” without their consent. A landmark decision on this law came in 1993, when the Supreme Court allowed TV game-show hostess Vanna White to sue over an ad that showed a robot styled like her, turning letters as she does on “Wheel of Fortune.”

“That was just a classic example of using somebody’s celebrity image without their authorization for commercial gain,” says Jeff Kobulnick, an intellectual property lawyer who has represented Kendall Jenner’s business. “That’s very similar to what’s going on as alleged in this case.”

Much could depend on the Forever 21 lawyers’ counterargument. Music lawyer Mattias Eng, whose recent work includes a legal credit on Travis Scott’s Astroworld, tells me this case reminds him of a $2.5 million verdict that Tom Waits won in 1990—over a Doritos ad that used an impersonator singing in the style of Waits’ “Step Right Up.” “But whereas the soundalike was close enough to confuse a listener whether the voice was indeed Tom Waits,” Eng says, “it may be more challenging to prove that a consumer seeing the images in question are confused whether they are actually of Ariana or not.” In other words, even though the model resembles Grande, would anyone actually mistake her for the singer?

Grande makes other legal claims that could potentially move forward, including copyright infringement of “7 rings.” But her case is notable more for the issues involving her likeness—an area that could become fertile ground for pop-star lawsuits moving forward. “The music business is no longer just about the music, it’s more than ever about the aesthetic, lifestyle, and influence surrounding celebrities,” says Abdo. Social media has made it easier than ever for musicians to use their image to sell products, perhaps rather than selling records. California’s right to publicity law extends 70 years after an artist’s death, and it covers holograms, Abdo notes. “There’s going to be very little tolerance by the artistic community for people who mess illegally with their name and likeness.”

Allegations of copying may be merely business as usual in the fast fashion industry. Just in the music world alone, Forever 21 has weathered accusations of imitating merchandise from Frank Ocean, Kanye West, Tupac Shakur, and even staunch DIY advocates Minor Threat. Once the fight with Grande is over, who knows if the company may continue this pattern and simply say, “thank u, next.”

Originally Appeared on Pitchfork