'It changed my life': Francis Ford Coppola reflects on The Godfather book's 50th anniversary

The following is the new introduction to Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, in a new edition pegged to the novel’s 50th anniversary, written by Francis Ford Coppola. He reflects on the novel’s legacy, how it changed his life, and more. Read on below. The Godfather‘s 50th anniversary edition is now available for purchase.

—

“YOU DIDN’T MAKE HIM, HE MADE YOU”

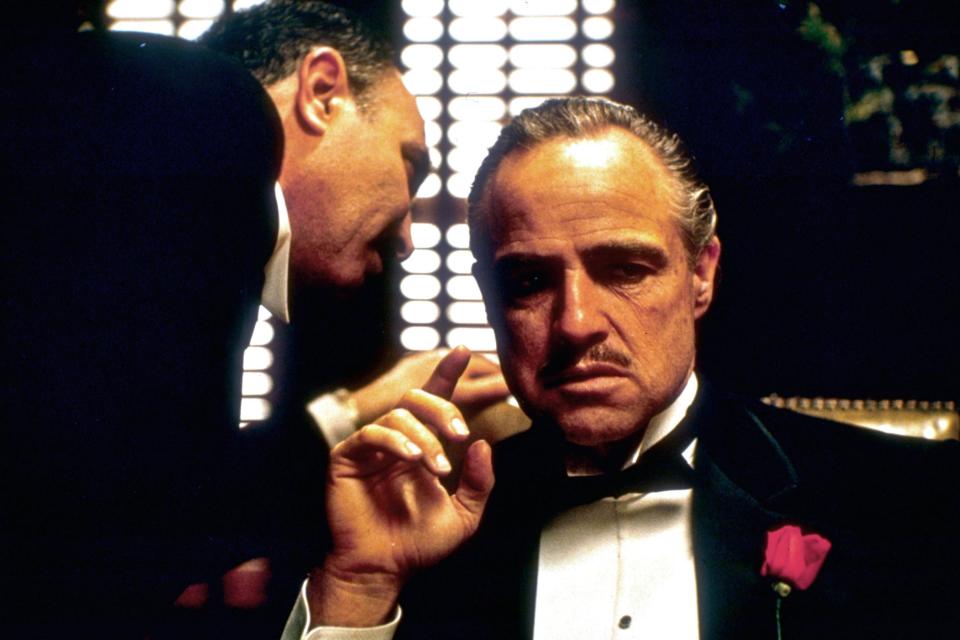

After the success of the movie The Godfather, I was in seventh heaven, the young man who’d caught lightning in a bottle. It was a heady time and a shock to a shy kid from Queens, a perpetually bad student who had been temporarily paralyzed by polio. One day I was in a group that included some suspiciously tough Italian men who were stealing glances at me, and talking among themselves. I heard the name Mario Puzo on their lips, and a guy who could have played Luca Brasi pushed his way over to me and said aggressively, “You didn’t make him, he made you!”

I didn’t disagree, and not just because I was intimidated by that assemblage of muscle. By then I was in my early thirties, and had gone from being an obscure, impoverished young director/writer to a household name. It is absolutely true that Mario “made” me and his novel The Godfather changed my life.

I had seen an ad in the New York Times book section for Mario Puzo’s The Godfather and I was struck by it because the illustration on the cover suggested a story about “power,” and the author’s Italian name made me think he was an intellectual on the order of Italo Calvino or Umberto Eco. So when I first sat down to read the book, my first impression was surprise and dismay; this was more like a Harold Robbins or Irving Wallace book, a potboiler filled with sex and silliness. I knew I was being considered to direct it and my first reaction was to turn it down. But needing the money and a film offer very badly, I decided to read it again and this time make careful notes. What I discovered was that lurking within was a great story almost classical in its nature; that of a king with three sons, each of whom had inherited an aspect of his personality. I thought that if I could just extract that part of the book and make the film about that, then I could work up some enthusiasm for it.

One thing I did love about Mario’s writing was that he was terse. He said in a few words what I would have taken a whole paragraph to express. This extended to his notes to me on the screenplay. In the scene where Clemenza describes a recipe to Michael, I had written, “First you brown some sausage, and then you throw in the tomatoes…” Mario scribbled, “Gangsters don’t ‘brown,’ gangsters ‘fry’.” And it was like that, throughout my draft of the script — just a handwritten note here and there, but they made a powerful difference.

As much as I admired his talent, his way of expressing himself on and off the page, I just loved to be around him. I loved him like a favorite uncle. He was so much fun to be with, so warm and wise, funny and affectionate. You would see it in the way he spoke of his wife of many years, the fact that he made his home in Bayshore, Long Island, and the way he spoke of his kids.

Mario loved to gamble, so I suggested that we go and stay at a gambling casino in Reno to work on the emerging script. (We did this for the scripts for all three films!) A casino is the perfect place for writers to collaborate. There are no clocks, so you can order up bacon and eggs (or anything) at any hour. When you reach a snag, you can always go downstairs to play roulette, which Mario loved to do. And then if you hit big losses (which Mario hated to do — he was a truly terrible gambler, despite knowing tons about it), you could escape back upstairs to continue working. Often he would say, “I’m losing thousands down here, but making millions upstairs.”

Mario knew his weight was a health hazard, and he would sometimes steal off to the Duke Fitness Center to do the “rice” diet. He’d lose 10 or 20 pounds but not really change his lifestyle, so the weight would always come back. I can see him now, dressed habitually in his exercise clothes (though I don’t recall any exercise to go with it), eating his beloved Italian food — pasta, pizza, lasagna… He shrugged off the inevitability of the weight coming back the same way he shrugged off his gambling losses — with a smile and a twinkling eye. He was a totally lovable man.

I learned so much from Mario, perhaps most importantly the need to rewrite and keep rewriting and not be daunted by doing more and more drafts. He also impressed on me the value of using everything that is important to your personal life. Mario told me that all of the great dialogue, those quotable lines he put into the mouth of Don Corleone, were actually spoken by Mario’s mother. Yes, “an offer he can’t refuse,” “keep your friends close but your enemies closer,” “revenge is a dish that tastes best cold,” and “a real man takes care of his family,” among many others, were sayings he heard from his own mother’s lips. Mario later wrote, “Whenever the Godfather opened his mouth, in my own mind I heard the voice of my mother. I heard her wisdom, her ruthlessness, and her unconquerable love for her family and life itself. Don Corleone’s courage and loyalty came from her, his humanity came from her.”

Despite his enormous knowledge of the Mob, the Cosa Nostra, all of that, it all came from research; Mario himself had never known a Mafioso. So another piece of advice he gave me was never meet them, never let them think they know you or that you are their acquaintance. It’s much like the lore of a vampire, who can never cross your threshold, unless he is invited. And I took that advice to heart, and never did I ever meet one of them. Once, during the filming of The Godfather Part II, I was in my mobile office and there was a knock on the one and only door (no escape route!). When my assistant opened it, a growl of a voice said, ”Mr. John Gotti is here and would like to make the acquaintance of Mr. Coppola.” Remembering Mario’s advice, I shook my head ‘”No.” My assistant politely said I was unavailable, they accepted that, and the door was closed on them.

After the great success of the first film, the owner of Paramount told me, “If you have the formula for Coca Cola you should make more of it.” In truth I had never thought that there should be a sequel to The Godfather film. Some stories lend themselves to additional chapters, but I felt this film was complete. Its protagonist-hero Michael Corleone has come full circle when he succeeds his father as “Godfather” and ultimately destroys what he had changed his life and person to protect: his family. However, there was one tempting aspect for me, and that was the story in the original novel about Vito Andolini, the young Sicilian who came to America after the brutal killings of his father and mother. Young Vito was gentle and kind, yet also had a cold rage inside that expressed itself as deadly cunning. That part of the novel just didn’t fit within the structure of The Godfather film, yet it was great and I was always sorry that we didn’t have a place for it in the movie. Also, I had always been interested in making a story about a father and a son in two different time periods. The father would be a character in the son’s story, as would the son in the father’s story. So little by little the idea presented itself of a structure that could become The Godfather Part II. As with the first script, I did the first pass, to lay it out and actually draft it, and then I sent it to Mario, and he made changes. Well, in reality he had done the first pass by writing his novel, and I was writing a ‘second draft’ in screenplay form. And then he would comment on that.

Not all of my ideas went over so well. Mario was dubious about the idea that it was Fredo who betrayed Michael; he didn’t think it was plausible. But he was absolutely against Michael ordering his own brother to be killed. It was a stalemate for a while, as nothing would happen unless we both agreed. Finally I tossed him the idea that Michael wouldn’t have Fredo killed until their mother died. He thought about this for a moment, and then said okay, it would work for him. He was the arbiter of what the novel’s characters would do, while I was offering a kind of interpretation from the perspective of what a movie director would do.

He also had a tough time with the notion that Kay would tell her husband that she had aborted their unborn son. Actually it was my sister, Talia, who came up with that idea. I loved it because it seemed symbolic and the only way a woman married to such a man could halt the satanic dance continuing generation after generation, which Nino Rota’s waltz theme expressed. Mario wasn’t sure about it, but he let me have it. He was a great collaborator, after all.

Meanwhile I pulled everything I could from the novel’s 1920s period, and how Vito became Don Vito and eventually the Godfather. And I interwove it with a story set in the 1950s concerning Michael and his stealthy opponent Hyman Roth, based on gangster Meyer Lansky. So I took parts of Mario’s novel and combined it with actual mob history to create the screenplay for The Godfather Part II. But I knew that it had been Mario Puzo who really did the heavy-lifting, and so I always insisted that it would be his name that appeared above the title: Mario Puzo’s THE GODFATHER.

Oh yes, then there’s The Godfather Part III, which neither Mario nor I wanted as the title, as it was not meant to be part of a trilogy, but rather a coda to the first two films, and we wished it could be given a different title, one more appropriate. Neither of us had the power to insist on our title but in my mind, the film will always be called The Death of Michael Corleone.

As usual, it was Mario who wrote whatever quotable lines it had. “Just when I get out, they pull me back in” was from him, though it perfectly expressed my own reality regarding the course of The Godfather! Just as my first impression of the original novel was that it was sensational and commercial, in fact it had won me over completely, and the more familiar I became with Mario’s work, the more impressed I was.

—Francis Ford Coppola