Angélique Kidjo on the Myth of Cultural Appropriation and Covering Remain in Light

Angélique Kidjo has never been a purist. When she was a child in Benin, a small vertical strip of a country along Africa’s arching western shoreline, her family exposed her to the music of the world. She learned the traditional folk forms of nearby villages right alongside soul and rock’n’roll imported from America, an at-home education that led her to fantasize about what life outside of Benin might be like.

In 1983, she began to find out: She escaped to France, fleeing a censorious dictatorship that demanded she use her burgeoning music career for state propaganda. Her musical universe expanded instantly in Paris, as she looked for new sounds with restless enthusiasm. At a college party, she heard “Once in a Lifetime,” the existential hit from the Talking Heads’ 1980 classic Remain in Light, and rightly recognized the African rhythms at work. But over the next two decades—even as Kidjo moved to New York, found an early champion in David Byrne, and became one of her generation’s true African crossover stars—she never listened to Remain in Light in full or even knew what it was called.

That changed after Donald Trump’s election in 2016. Kidjo’s husband, French musician Jean Hébrail, heard her humming “Once in a Lifetime” as she often had and suggested she finally listen to Remain in Light. She not only heard echoes of Africa again (particularly Afrobeat architect Fela Kuti) but also now recognized the record’s political discomfort and social unease. She decided to cover it in full, a project she says became her “solution for expressing anxiety about the future.”

Recorded with hip-hop producer Jeff Bhasker and players including Kuti drummer Tony Allen and Vampire Weekend frontman Ezra Koenig, Kidjo’s irrepressible take on Remain in Light is a new benchmark in an already accomplished career and one of the year’s most daring records. She gives these songs new African roots, pushing them upwards with surges of horns and choirs. Powerful drums provide the Talking Heads’ skeletal beats with new muscle and movement. Kidjo also rewrote some of the lyrics and added traditional African parables and songs in the background, reinforcing the idea that these anxieties are omnipresent and ageless. On the album (out this week), she triumphs over them.

Over the years, critics have occasionally scorned Kidjo for not sounding “African” enough, perhaps because she would bend her voice into R&B curves or add the likes of Bono and Dr. John to her songs. But she’s insisted that African music shouldn’t stand still or be confined by some outsider’s purity test. Remain in Light is her ultimate kiss-off to such notions, an unapologetic declaration that she can decide for herself how African music should sound or who can make it. Calling from a photoshoot in New York City, Kidjo spoke at length about her belief that cultural appropriation is a myth limiting us all. Compiled from our conversations, she explains, in her own words, how she came to this conclusion.

People don’t realize the privilege of their freedom. The dictatorship in Benin was very difficult for me as a free artist. Music from all around the world stopped coming in the middle of the ’70s. They said no more music from the outside, so the radio and TV became propaganda. Every artist was summoned to write propaganda. I refused.

By the time I got to Paris in 1983, I had not listened to anything else but that stupid BS. When I arrived, I was ready to listen to everything. I am not addicted to any substance, but I became the junkie of music. I felt the world had passed me by for more than 10 years, and I had so much to catch up with.

At a music-school party that same year, “Once in a Lifetime” came on. Everybody was sitting down, talking, but I was moving. I said, “This is African!” They said, “No, you are not sophisticated enough in Africa to understand and do this kind of music.” But I was humming, singing along with the chorus. It seemed natural. I wished my mom and dad were there so we could do what we do at home: We all start dancing and singing, even if you don’t know the lyrics. With my sense of solitude and loneliness and longing, that song brought me back home for the rest of the party.

No one told me the name of the song or the band, but it stuck. Fast forward to New York a few years ago: I was humming the song, and my husband said, “Do you know what you’re singing?” I said, “I just heard it when I came to Paris, but I never knew what it was.” He said, “This is one of the biggest songs from the album Remain in Light.” I listened to the whole album. It was like you have gone ahead of time and now time has caught up with you.

People were telling me, “The lyrics are absurd.” Not in my mind, not from where I come from. This album came out in the Reagan era, and we’re living in the same thing now. We are living in a war against democracy and a war against people’s rights. The thing I felt was anxiety.

When I hear something that resonates in my soul, it’s always through the lens of my country, my traditional music. Every song on Remain in Light comes with a message. It became obvious that “Born Under Punches”—man, it means nothing to you Americans—means corruption. It reminded me of so many songs that I used to listen to when I was a little kid. The one that comes to mind is what I put in the background of “Born Under Punches”: “Fire can make you dizzy/And you cannot play with fire if you don’t know how to handle fire/You can start a fire of corruption, but if you don’t know how to handle it, that fire is going to eat you up.” With “Crosseyed and Painless,” it became, where is the truth? Without truth, there is no society. “Listening Wind”—that’s the story of conquest. You come in, you conquer, you leave—but you don’t leave people’s culture. For me, this album put things in perspective: We have made choices that have destroyed society. Will we have the courage to change these choices?

The only thing that could have made my take on Remain in Light work was for it to be based in percussion—building the songs up with percussion and voice. When you listen to “Once in a Lifetime,” I am calling you with my drum to ask yourself: How did we get here? Are we wrong? Are we right? What are we doing? That’s how we start the conversation about transforming our world to be more humane, not profit-driven and heartless. That’s why I made Remain in Light and “Once in a Lifetime” so uplifting, so joyful. The question has to get us into action.

David Byrne did an interview when the album was released, telling people to listen to Fela Kuti and to read books about African music. What he learned by reading those books was the way drums are used in West Africa. The repetitive patterns of the drums bring you to a trance. That’s where the idea of looping comes in place, like the bassline that played the same all through one song.

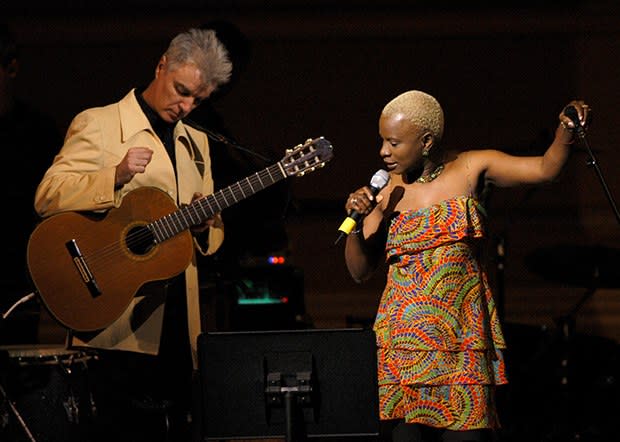

David Byrne Angélique Kidjo

People told them it was too pretentious, but the Talking Heads were very honest from the get-go. From the moment you give credit to the people who inspire you, and you don’t copy their songs, it’s not cultural appropriation, it’s cultural expression. With Elvis Presley, that’s not the case. He stole the songs. When you blatantly take a song and put your name on it, that is not cultural appropriation—it’s stealing! If you recognize where it came from, no problem. It’s not cultural appropriation to me when you acknowledge it.

No matter what we call ourselves, we all are inspired by somebody, by music we’ve been listening to. Is that a crime? No. For me, that’s the beauty of music. We bounce off each other. We can be two talented musicians, have the same song, and interpret it completely differently. If you go to Africa to work with African artists, be respectful. Listen to them. Listen to each other. But if you get there with your attitude and you’re arrogant, the people are going to look at you and say, “Well, if that’s how you want to play...” They won’t teach you nothing. They’ll just try to impress you, then they laugh when you leave.

There’s an artist called Ali Farka Touré in Mali, and everybody says, “Oh, Mali is the place of the blues.” But the blues is everywhere in Africa in different forms, in different languages. He was listening to all those old bluesmen from the South, from Mississippi, when he was a little kid. He tuned his guitar differently. Music doesn’t stay. It goes back and forth. It moves and evolves. When you bring something new somewhere, somebody touches it. It’s never going to be the same as before, but otherwise it dies. I’ve been raised believing that culture—my culture—is not mine to keep. I have to share it with people.

Everywhere Africans go, we are always second- or third-class participants in our own art. When you come from Africa, there’s a place already set in the narrative for you. How many Africans do you see in any media in America on primetime? We have to sing in English before we make it to the TV. But everybody has been inspired by the music of Africa. The blues come from where? Africa! Everything we’ve been playing is in our DNA, because we all come from Africa. But it doesn’t matter where you live. When you listen to music your skin color doesn’t matter. The only thing that matters is what you feel.

One of the main reasons I’ve spent so much time doing Remain in Light is because rock’n’roll is not big in Africa. People there say, “Where’s the four on the floor? We can’t dance to this! It’s white people stuff.” They call me Mother Teresa because I’m always like, “You can’t talk like that. It’s not about white and black.” So I’m bringing rock’n’roll back to Africa. If African people can groove on this, I’m going to sit back and say, “OK, now, you’re dancing to rock’n’roll.”

I’ve always been thankful for all the different kinds of artists that my parents were able to bring to me. My father would say, “Music is the language you speak. You belong to that. The music I’m bringing home is for you to be able to get out of this house, and wherever you go, you’ll feel comfortable.” When I was a kid, my family was not rich. The only way for me to travel was to listen to music—to imagine where that music came from, what the person that wrote that music was doing.

Most of the languages of the music, I didn’t speak them, but I didn’t care. When I started singing these songs, I didn’t know a word of English. My passion for English started with James Brown. “What is this language that is so funky, man?” If I can hear a rhythm in any language, I’m going for it. I’ve worked on projects where not two people will speak English or French. As soon as we start trying to explain to each other, it becomes a nightmare. But we just take the instrument we play, and then there’s no more discussion.

My knowledge about the concept of being an African and an American came from Jimi Hendrix, because of his Afro. When my brother taught himself to play guitar, he put an Afro wig on his head. I am like, “What the hell is going on? Do you need an Afro wig before you play guitar?” He said, “I want to look like him!” I said, “Who is that guy, anyway?” He said, “He’s an African-American?” How can you be an African and an American at the same time, I wanted to know. It’s two different continents. The music had brought me to ask questions. What is my place in this world?

I get tired of people who call themselves purists. Before you start talking about “purity,” look at yourself: Are you pure? What is pure in your surroundings? What is pure in nature? The rhetoric of purity, that’s what brought Hitler to power—looking for a pure race. We are not perfect, and that’s why we are brothers and sisters. The fact that we keep ourselves divided is exactly what the people in power want us to do. The more divided you are, the more power you give them, and the more they can kill you.