Andy Warhol Ruling Limits Fair Use for Copyrighted Images, With Far-Reaching Hollywood Implications

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

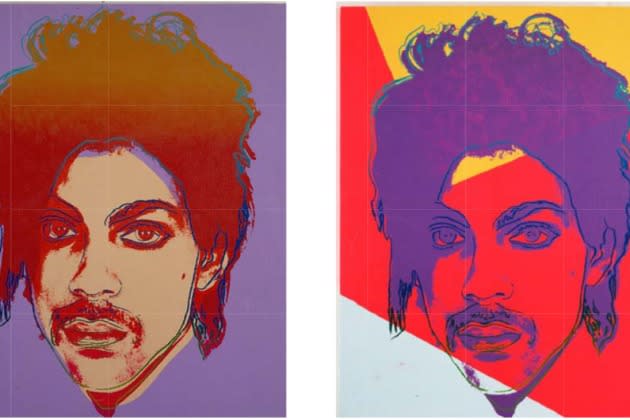

Andy Warhol wasn’t allowed to use a photographer’s portrait of Prince for a series of pop-art images, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled Thursday in a decision limiting the reach of the fair use defense to copyright infringement claims.

Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, writing for the majority in the 7-2 decision, found that the Lynn Goldsmith’s “original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists” like Warhol. Potentially overlapping commercial exploitation of the works was a key consideration.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Si Litvinoff, 'Clockwork Orange' and 'Man Who Fell to Earth' Producer, Dies at 93

Copyright Battle Over Warhol's Prince Series Headed for Supreme Court

“The purpose of the image is substantially the same as that of Goldsmith’s photograph,“ she wrote. “Both are portraits of Prince used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince.”

Associate Justice Elena Kagan, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, sided with Warhol in a dissent saying that the majority is “uninterested in the distinctiveness and newness of Warhol’s portrait.” She warned that the decision “will impede new art and music and literature” and “thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge.”

Goldsmith, a prominent rock photographer, was hired by Newsweek in 1981 to take pictures of Prince. Three years after the magazine ran the photo, Vanity Fair asked Warhol to create a portrait of Prince using Goldsmith’s photo as a template, for which she was paid $400 to license the portrait and use it for a single issue. But, unknown to the photographer, Warhol created a series of 16 images, cropping and painting over the original images to make what his foundation’s lawyers argue are entirely new creations that comment on celebrity and consumerism. The works have been displayed in museums, galleries and other distinguished public venues and have sold for over six figures.

After Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair’s parent company Condé Nast ran an image from the series on the cover. It paid the Andy Warhol Foundation, which assumed ownership of the series, $10,250. Goldsmith got nothing. When she claimed that the work infringed on her copyright and asked for compensation, the foundation sued her seeking a court declaration that the work is protected by fair use.

The case has bounced between federal and appellate courts, with most of the disagreement focused on whether Warhol sufficiently changed Goldsmith’s photo — a key element in determining whether a work qualifies for fair use protection. It tests the reach of the defense and how courts should evaluate if works based on others are meaningfully transformative enough to qualify as a different piece. In 2019, a New York federal judge sided with Warhol that the Prince series qualifies as a new and distinct piece of art by incorporating a new meaning and message. A federal appeals court in 2021 overturned the decision.

The sole question answered by the Supreme Court is whether the first fair use factor — the purpose and character of the use — weighs in favor of the foundation. The majority stressed that an analysis of whether the secondary work was sufficiently transformed to protect against copyright infringement must also weigh the commercial nature of the use.

Responding to the foundation’s claim that the Prince series is “transformative” since it conveys a different meaning or message than Goldsmith’s photograph, Sotomayor concluded that the first fair use factor actually “focuses on whether an allegedly infringing use has a further purpose or different character, which is a matter of degree, and the degree of difference must be weighed against other considerations, like commercialism.”

Although new expression, meaning or message may be relevant to this balancing test, it’s not absolutely determinative, according to the ruling.

With respect to the works from Goldsmith and Warhol, the majority found that they “share substantially the same purpose,” even though the pop art image does add new expression to the original portrait. It explained that the foundation’s commercial exploitation of the Prince series tilts the scale even further in favor of the photographer’s argument that fair use shouldn’t apply, stressing that Goldsmith had previously licensed her photos of Prince to publications.

“In sum, if an original work and secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is commercial, the first fair use factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying,” Sotomayor wrote. She noted that ruling the other way would essentially permit artists to make slight alterations to an original photograph and sell it by claiming transformative use.

Intellectual property lawyer Bruce Ewing says that by emphasizing the importance of commercial exploitation, the court has “rewritten an entire body of case law” that had previously focused the analysis on whether the challenged work was transformative.

“While the question of whether a later work has transformed a prior work by adding new meaning or message remains relevant, such additions will not by themselves tilt the first factor in favor of fair use, as most cases had held previously,” says Ewing. “Under today’s ruling, the first factor will only favor fair use if the newly added material rises to such a sufficiently transformative level that the new work achieves a different purpose than that of the prior work, and therefore does not supersede it.”

Nicole Haff, an intellectual property lawyer, emphasized the significance of the ruling considering the potentially duplicative commercial exploitation of the works.

“If this conduct was ruled to be ‘fair use,’ it would essentially cut Goldsmith out of her opportunity to earn money by licensing her photograph or otherwise creating derivative works of the photograph,” Haff says. “This would not support the purpose of the Copyright Act, which is to promote the progress of science and useful arts.”

Other uses of Warhol’s silkscreens in a nonprofit or museum or book may be considered fair use because they “do not act as commercial substitutes,” says Stephanie Bunting, an intellectual property attorney.

Kagan, leading a strongly worded dissent aimed at what she called “the majority’s lack of appreciation for the way [Warhol’s] works differ in both aesthetics and message from the original templates,” argues that commercial exploitation was given too much importance in considering fair use. She pointed to the court, in a recent decision, using Warhol paintings as the “perfect exemplar of a ‘copying use that adds something new and important’ — of a use that is ‘transformative.'”

“That Court would have told this one to go back to school,” Kagan wrote. “What is worse, that refresher course would apparently be insufficient. For it is not just that the majority does not realize how much Warhol added; it is that the majority does not care.”

Sotomayor responded in a footnote that the “dissent is stumped,” calling one of its arguments a “Hail Mary.”

The case was sent back to the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which will in turn return it to New York federal court. A finding of copyright infringement looms since the appeals court already found that the works are substantially similar.

Joel Wachs, president of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, stressed in a statement that he court’s ruling is “limited to that single licensing and does not question the legality of Andy Warhol’s creation of the Prince Series in 1984.”

A music industry trade group also chimed in. In a statement, the Recording Industry Association of America CEO Mitch Glazier says, “We applaud the Supreme Court’s considered and thoughtful decision that claims of ‘transformative use’ cannot undermine the basic rights given to all creators under the Copyright Act.”

“Lower courts have misconstrued fair use for too long and we are grateful the Supreme Court has reaffirmed the core purposes of copyright,” Glazier adds. “We hope those who have relied on distorted — and now discredited — claims of ‘transformative use,’ such as those who use copyrighted works to train artificial intelligence systems without authorization, will revisit their practices in light of this important ruling.”

As for its potential effect on the hot-button issue of artificial intelligence and copyright, patent attorney Randy McCarthy says that, under this ruling, the legality of AI using copyrighted works to train their systems will turn on whether the “output is sufficiently transformed and the input cannot be easily identified from an examination of the output content.”

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Meet the World Builders: Hollywood's Top Physical Production Executives of 2023

Men in Blazers, Hollywood’s Favorite Soccer Podcast, Aims for a Global Empire