American men's drought continues after Sam Querrey loss at Wimbledon

The Cinderella run is over for the last standing American man. Marin Cilic of Croatia defeated Sam Querrey 6-7(6-8), 6-4, 7-6(7-3), 7-5 in the Wimbledon semifinal. And with that, the American men’s drought of nearly 14 major title-less years continues.

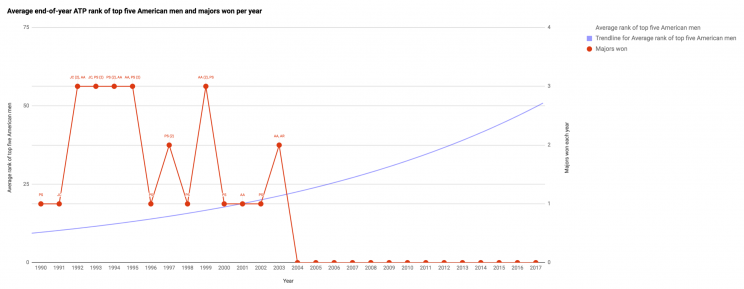

It’s no secret that American tennis has been on the downfall. Long gone are the days of McEnroe and Sampras serving-and-volleying their way to major titles. The best days of Andy Roddick, the last American slam winner and a huge server himself, are a fading memory. Roddick’s rise coincided with the tail end of American dominance — yes, dominance — in men’s tennis. Just how far has men’s tennis fallen? A long, long way:

As the chart shows, American men’s tennis simply doesn’t have the top-end talent it did during its decade-long 1990s reign. Take, for example, the ATP rankings at the end of the 1992 calendar year. All five of the top-ranked U.S. men — Jim Courier (1), Pete Sampras (3), Michael Chang (6), Ivan Lendl (8) and Andre Agassi (9) — were inside the top 10 worldwide. This was due in some part to Lendl’s becoming an American citizen earlier in the year, but the overall sentiment still rings overwhelmingly true. Americans had captured three of the four majors that year and would do so for the next three straight years.

Twenty-five years later, the highest-ranked American is No. 18 Jack Sock, who crashed out of Wimbledon in the second round. Querrey’s semifinal appearance was the first from any American man since Roddick in 2009. Simply put, the massive struggles of American men’s tennis, though often swept under the rug, is alarming.

One thing to point to is the age difference between the top Americans in the 1990s and the top Americans today. In that vaunted 1992 year, for example, four of the top five men were 22 or younger. None attended college, all turning pro by 18 years old at the latest. Of the current top five Americans today, just one — Sock — is under 25, and two attended college.

The debate over whether or not top tennis prospects should go to college isn’t a new one. Steve Johnson, currently 31st in the world, finished his college career at Southern Cal on a 72-match win streak. Widely regarded as the best college tennis player ever, the now 27-year-old has won just two ATP tournaments since turning pro in 2011 but has never been to a slam quarterfinal. Donald Young, on the other hand, never came close to college, turning pro at 16 after becoming the world’s top youth player. Over a decade later, Young is yet to claim any ATP title and, like Johnson, hasn’t made it past the fourth round in a major.

Of course, none of the current top players in the world went to college.

“In Europe, sports are not seen as tickets into universities, as athletic competition between schools is not emphasized and athletic scholarships are extremely rare,” Philip Sopher wrote in 2014. “So European juniors go pro as soon as they can.”

Perhaps some conclusions can be drawn from the setup of youth circuits. The United States depends heavily on academies to produce top U.S. talent. Sampras, Agassi and Courier all attended IMG Academy in Florida. For most of Europe’s top players, regional or national tennis centers are the destination for top adolescent players. That also means more access to top-notch coaching and competition. It means more ATP Futures and more ATP Challengers events. Patrick McEnroe, who served as USTA head of player development from 2008 to 2014, played a key role in the construction of 17 regional centers. This year brought the opening of a national campus in Florida. Consolidating tennis talent and bringing it under the best coaches is a significant step forward. These changes do take time, though. The United States is in the early stages of building what Europe has had for decades.

Of course, there are countless other reasons for the United States struggling. Earnings on the ATP can’t compare to that of the Big Four sports. Per a 2013 ESPN study, tennis is the eighth-most popular sport among American male adolescents. Tennis is generally believed to be second to soccer in Europe. American dominance was built off the serve-and-volley tactics that are only used on occasion in today’s game. Tennis, like golf, still struggles to reach the non-upper class in America, but high-quality, low-cost coaching is more widely available in Europe.

It’s also worth pointing out that no single country is dominating like Australia did in the 1950s and 60s, the United States did in the ’70s and ’90s and Sweden did in the ’80s. American tennis in the 1990s is the last time any country dominated mens tennis so thoroughly. Right now, nine countries are represented in the top 10. The only country with multiple players in the top 10, Switzerland, doesn’t have another player in the top 100. When looked at from that angle, it’s not that the United States lacks talent. It’s that the United States lacks a single individual — a Roger Federer, a Rafael Nadal, a Novak Djokovic or an Andy Murray — who can challenge for a title. One individual can change the entire narrative.

Just look on the women’s side. Serena Williams and, to a lesser extent, Venus Williams have propelled the country. The last non-Williams sister American to win a slam was Jennifer Capriati in 2002. If one American man could be even an occasional winner, the perception of American men’s tennis would be very different.

There is reason for tepid optimism, too. Americans Jared Donaldson and Frances Tiafoe, 20 and 19 respectively, are both top-70 players. Donaldson recently made a career-best run to the third round at Wimbledon. Tiafoe was one of the top youth players in the world. Ernesto Escobedo, 20, also falls in the top 100. There are several more youngsters who dot the top 300 or so. The question is whether they’ll become actual contenders and if so, how quickly.

Some European youth are already there. German 20-year-old Alexander Zverev showed how far Tiafoe is from contending in a clinical three-set win in the second round at the All England Club. There are plenty of other Europeans under 25 who have made deep runs into majors. No young American has done so, though. One youngster has to deliver on the promise the group as a whole has shown.

So yes, the top Americans have fallen in the world rankings. They haven’t produced a champion in nearly a decade-and-a-half, by far the longest drought ever. (The previous longest drought was five years, from 1985-89.) But no country has ever dominated like the U.S. in the 1990s (21 major victories), and expecting a return to those standards is unfair. All four members of the Big Four — a group that has taken 47 of the 54 slams (over 87 percent) since Roddick won the U.S. Open, are into their 30s. There’s certainly opportunity around the corner for the young American talent to turn over a new leaf in a new era. Whether they can catch their European peers, though, remains to be seen.

Vikram Bodas contributed to this story.